Moving to Lake Arrowhead wasn’t always part of Natalie Camunas’ plan.

When the 35-year-old and her partner purchased a small cabin in the mountains two years ago, they intended to use it as an investment property that they would rent out to vacationers looking for a forest escape. The couple bought the 670-square-foot home for $189,000, Camunas said, when housing prices in Southern California were climbing but before they smashed records and hit an all-time high.

But after quarantining in their apartment in Los Angeles’ Fairfax district as the COVID-19 pandemic spread, discovering dead rats in their home and dealing with a bug infestation, they decided to make their move to San Bernardino County official in the fall of 2020.

“We were paying all this money to be at the center of things, but everything was shut down, and there was no center anymore,” Camunas, an actor, said. “Looking at homes in L.A., it was ridiculous. Even if we could afford a $900,000 home, we didn’t want that. We didn’t want a mortgage that was $5,000.”

Los Angeles lost more residents than any other county in the nation during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, new census data show.

Across the state, Californians in search of more open space, a sense of community and affordable housing are trading city life in major urban centers like the Bay Area or Los Angeles for suburban and rural communities. A growing number of families have moved inland over the last few years, data show, but the migratory shift grew even more pronounced amid the pandemic as the barriers to moving dropped for many in large cities, spurred by a newfound ability to work remotely.

Both Los Angeles and San Francisco saw sizable declines in population during the first year of the pandemic, census data show, underscoring how California’s housing crisis and other demographic forces are reshaping two of its largest cities. But as those cities shrank, several adjacent counties saw population gain, including Riverside, San Bernardino, San Joaquin and Kern.

Many who move to inland cities say they are drawn by more affordable housing, new job sources and the chance to escape big-city hustle — even if the reality of rural life doesn’t always match glossy Instagram portrayals.

For the first year and a half, Camunas missed her life in L.A.’s Fairfax district: the food, the freedom to window-shop when she wanted to get out of the house.

Winter in the mountains came with a steep learning curve, she said. Last December, a tree fell on a transformer and blew out most of the mountain’s electricity. Camunas and partner Amy Kneupper lost heat in their cabin for about 12 days and lost power for about six.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“Our olive oil froze. It was about 30 degrees in here,” she said. “That was a moment that was like, ‘Why am I paying money to live in a climate that’s trying to kill me?’” she said, laughing.

But the pair navigated through the seasons, eventually buying a generator, snow-clearing tools and realizing they would “always need to have firewood.” Their $1,220 mortgage payment is less than half the $3,000 rent they were paying in Fairfax, Camunas said. They put their money toward renovating the house — painting it white, and changing the uneven cabinets to a more modern style.

Some of their friends moved to the same area by coincidence, she said, surrounding the couple with a community of people who work in the industry and who either telecommute or make the occasional trip to the city for their jobs.

“I took up skiing,” Camunas said. “We kayak on the lake, and I freaking love it. I still go into the city a fair amount ... but it now very much feels like the best of both worlds. I go to the city, rev up my battery, get my fix of sushi and Indian food, and I come home and I rest. It’s so safe and so quiet, and our dog is so happy.”

Some city dwellers who’ve moved to the high desert over the last year and a half looking for more space and clean air also found unexpected drawbacks.

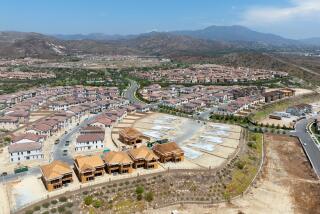

Growth in the Inland Empire has been so explosive in recent years that the San Bernardino-Riverside-Ontario Metropolitan Statistical Area last year surpassed that of San Francisco to become the 12th-largest in the United States, with more than 4.6 million residents as of July 2021.

Riverside County gained nearly 36,000 residents between July 2020 and July 2021 — the third-highest countywide population gain in the nation, trailing only Maricopa County in Arizona and Collin County, Texas, according to census data. San Bernardino county grew by 11,970 people.

“People need to realize how large the region is,” said Paul Granillo, president and chief executive of the Inland Empire Economic Partnership. “The growth is nothing new: We’ve grown by 50- or 60,000 people a year. The city of Eastvale, which is a city of 65,000 people, didn’t exist 10 years ago. That’s just part of the reality of the Inland Empire.”

Although growth in the area has been steady for decades, Granillo said it accelerated during the pandemic due to many of the same factors propelling people to make moves around the country, including more work-from-home options and soaring housing prices in neighboring counties.

“The big driver has always been housing affordability,” he said.

In the decade after the Great Recession, the Inland Empire also led the country in job growth, Granillo said, noting that the area’s goods-movement sector is among the largest in the world.

“The ports of L.A. and Long Beach can’t do their job unless the warehousing is available in the Inland Empire,” Granillo said.

He added that 42% of all goods that enter through the ports pass through the Inland Empire before heading to the rest of the country. Amazon’s biggest footprint in the U.S. is in the Inland Empire, and “all the major players,” including Walmart and Target, have warehouses there, he said.

A recent regional outlook report from the Rose Institute at Claremont McKenna College identified Highgrove, Beaumont and Lake Elsinore among those Riverside County areas that experienced the most growth between 2010 and 2020. Adelanto, Chino and Victorville were among the areas with the most growth in San Bernardino County.

Musician and teacher Trevor Jackson, 24, recently made the move from his hometown of San Diego to the city of Riverside after a room opened up in one of his bandmate’s houses.

“My partner and I decided to move up here, as the cost of living is cheaper here in Riverside than it was in the suburbs of San Diego,” Jackson said. “Right now, we are extremely close to a handful of centers and schools, equating to amazing walkability, which is what convinced us to move.”

Jackson said he also liked that the area is less than an hour from Los Angeles, which he said is a “plus for my line of work.” He might try to open a teaching and recording studio in Riverside or Long Beach in the future, he said.

“The beauty of the surrounding mountains really surprised me,” he said.

Southern California home prices hit a record high in December, the 10th record in 2021. Analysts see the housing market cooling slightly this year.

Although Riverside has seen the most growth of any county in California, other inland parts of the state are gaining residents, too. Kern County grew by more than 7,600 residents between July 2020 and July 2021, according to census data, while San Joaquin County saw 8,893 newcomers.

Suzanne Rodriguez, a Kern County Realtor who was born and raised in the Bakersfield area, said that some booming enclaves of the county didn’t exist when she was in high school, including areas along the western edge of Bakersfield.

“The housing increase that we saw during the 2000s has expanded the city so greatly,” Rodriguez said. “Now we’re seeing this new wave of not necessarily new homes that are being built, but a new group of people coming here — people who maybe would never have looked at Kern County or Bakersfield before.”

The median home sale price in Bakersfield in March was $365,000, she said. In the Los Angeles Metro area, that number was $770,000, according to the California Assn. of Realtors.

“There’s a lot of local first-time home buyers, there’s a lot of out-of-town first-time homebuyers,” Rodriguez said. “People just really hungry to get into a home.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.