The coroner said Frankie died, but he’s still alive. Now O.C. has to pay $1.5 million

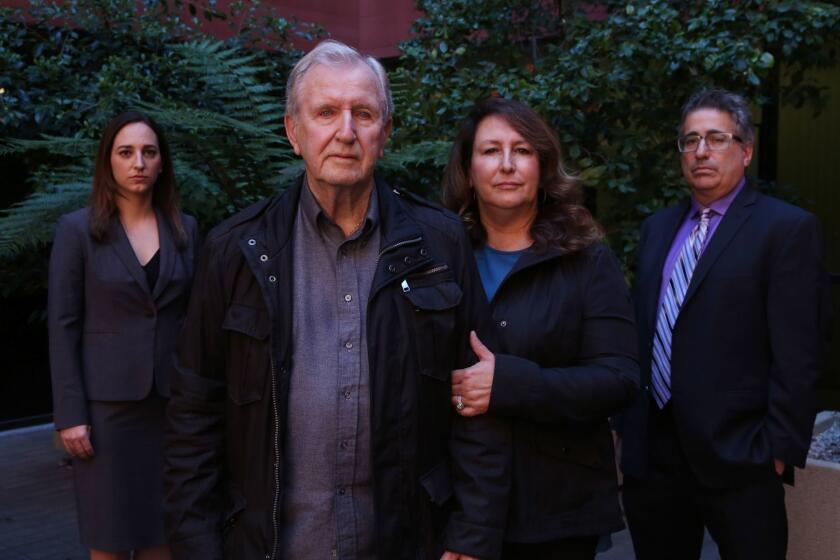

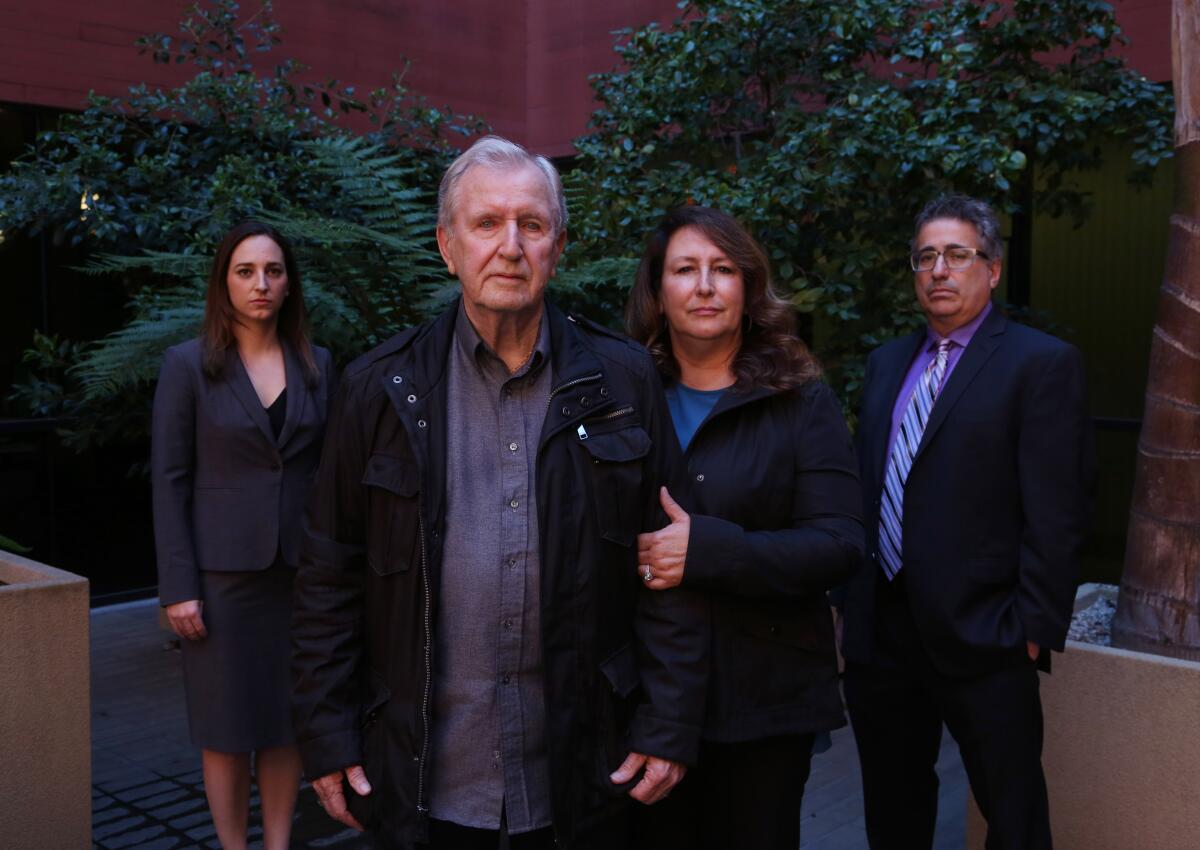

Soon after the Orange County coroner’s office told him his eldest son had died, 81-year-old Francis Kerrigan went to the scene. It was a patch of blood-smeared pavement outside a Verizon store at a Fountain Valley strip mall.

Frankie Kerrigan, 57, had profound schizophrenia, and had been on and off the streets for a decade. He resisted taking his medication, and tended to bolt if his family pushed. It looked like he had died violently on May 6, 2017.

The grieving father, a retired electrical engineer, had talked to his son just days earlier. Now he was on his hands and knees, searching the pavement for anything his son had left behind. He found someone’s boot, but none of the three things he knew his son always carried — a pen, a wristwatch and a black attaché case.

A body was delivered to the Kerrigans. There was a wake, a Catholic Mass and a burial in a family plot. On May 23 — 17 days after the death notification — a family friend called Francis Kerrigan to say the son he’d been mourning had just appeared at his house. He had his ubiquitous black attaché case.

The body in the ground was another homeless man, John Dean Dickens, 54, who died of heart disease. On Tuesday, an Orange County Superior Court jury found the coroner’s office committed negligence and intentional misrepresentation, and awarded the Kerrigan family $1.5 million in damages.

“My worst fear was my brother would die alone in a pile of blood on a sidewalk,” Carole Meikle, one of the plaintiffs, testified.

She said the strip mall where her brother supposedly died used to be orange groves and a drive-in theater where the family had spent many summers. After the death notification, she went to the scene and put up a shrine, with her brother’s photo and a note: “Rest in Peace. Your family loves you.”

Authorities on Friday released the name of a man found dead in May and buried by the wrong family because of a botched identification by Orange County coroner’s officials.

When she learned her brother was alive, she said she fell to her knees. “This doesn’t ever happen,” she said. Another family member compared it to an experience out of “The Twilight Zone.”

The coroner’s office admitted its mistake, and testimony at the trial in Santa Ana shed light on how it happened. It began when a Fountain Valley police officer told a veteran deputy coroner, David Ralsten, that the body found outside the Verizon store seemed to resemble Frankie Kerrigan, a man known to live on the area’s streets.

Ralsten called up an 11-year-old DMV photo of Kerrigan and compared it to the face of the corpse, whose features were obscured by blood and vomit. He thought the noses had a similar width, and that the chins were the same.

“I did look at multiple features,” Ralsten, now retired, testified. “They did appear to be the same person, Mr. Kerrigan and the deceased.”

Ralsten made a positive identification of the body as Kerrigan’s, which led to the family notification, but he expected the ID would be confirmed by fingerprints.

Prints were taken from the body and checked against local, state and federal databases, which quickly established the body belonged to Dickens, not Kerrigan. But Ralsten went on vacation, and no one at the coroner’s office bothered to check the system, which had been installed five months earlier. “We essentially had no significant training” on it, Ralsten said.

“It’s just inexcusable that the coroner’s office doesn’t understand how their system worked,” V. James DeSimone, the plaintiffs’ attorney, told jurors.

DeSimone stressed the emotional anguish of the Kerrigans’ experience. “They felt their son died there on that sidewalk,” DeSimone said. “This is going to haunt the Kerrigan family for the rest of their lives.”

Consumed by grief, Francis Kerrigan attended an open-casket viewing of the body that was supposed to be his son, and did not recognize it was the wrong person.

“I touched his hair, and I said goodbye,” Kerrigan testified. When he received the call that his son was alive, he said, “I was overjoyed for about a minute.”

Then he thought: “Oh my God, there’s a stranger in Frankie’s grave.”

His son is alive, and safe in a hotel, but doesn’t understand what happened. “I have a dead son and a live son right now,” he said. “I don’t know how else to express it.”

In their lawsuit and at trial, the Kerrigans raised the possibility that there were actually two cadavers involved in the case, pointing to discrepancies between an on-scene coroner report — which noted edema in the back, hips and legs — and an autopsy report, which noted edema only in the feet and ankles. One report noted lacerations around the eye; the other did not.

The lawsuit alleged that officials decided to cover up their initial misidentification by sending someone else’s body — a rough lookalike — to the funeral home.

The Orange County Sheriff-Coroner has yet to explain how authorities identified a homeless man found dead behind a phone store last May as 57-year-old Frankie M.

The theory seemed far-fetched to Judge Theodore Howard. Speaking to lawyers outside the presence of the jury, he asked when the bodies were supposedly switched. “Somewhere between Fountain Valley and the coroner’s office?” the judge said. “That’s just ridiculous.”

No evidence emerged during trial establishing there was a second body. Norman J. Watkins, the lawyer representing the county, characterized the theory as “wildly crazy” and “insanity, plain and simple.” He told jurors the Kerrigans had “invented a cover-up conspiracy” involving “body-snatching or body-switching” in a bid for money.

“How many employees would it take to engineer swapping out bodies?” Watkins said. “Who would even think of such a thing?”

Jurors awarded $1.1 million to Francis Kerrigan and $400,000 to Meikle, his daughter, far less than the $10 million their lawyer had suggested.

DeSimone said jurors told him the body-switch theory did not figure into their deliberations.

He said the family hopes the jury verdict will help them care for Frankie Kerrigan, but that it is dangerous to inform him about the trial and its outcome. He has an aversion to authority.

“Frankie is relatively stable, with a roof over his head,” DeSimone said. “They’re hoping to get him back on medication. If he has some inclination there’s a court case going on, they’re afraid he’ll just bolt.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.