Years before her death last summer at the age of 85, Lois Woodburn cornered a mortician at a party to ask if she could be buried in the ocean.

Lots of people want their cremated remains scattered in the sea, but that’s not what Woodburn, a fun-loving commercial artist, had in mind.

“She said, ‘My whole body in there. Just throw me in the ocean. That’s what I want,’” said her daughter, Teresa Stremcha.

The mortician explained that a full body burial at sea is a bit more complicated than simply heaving a corpse overboard. But it is possible, and legal, as long as certain protocols are followed.

As Woodburn’s health declined, Stremcha asked her mother again and again if she wanted a sea burial, or if she would prefer a more traditional burial at a cemetery in Inglewood.

Woodburn never wavered. She loved the ocean and didn’t want to be stuck in the ground. When her time came, Stremcha said, she wanted to be buried in her favorite black bathing suit.

“That was my grandma,” said Stremcha’s son, Daniel Reffner. “She was always dressing for the occasion.”

And so one morning last August, about 30 of Woodburn’s family and friends took a yacht from Long Beach Harbor to a spot six miles offshore to watch the crew on a second boat slide Woodburn’s stainless steel casket into the ocean. It bobbed on the water for a few moments and then tipped forward, slipping quietly beneath the waves.

Now, Stremcha’s husband and her daughter hope to be buried the same way.

“After seeing that, everyone wants to go to sea,” Stremcha said.

Full body burials at sea are not new, but they are rare. Ken McKenzie, a funeral director who runs McKenzie Mortuary Services in Long Beach and recently acquired Armstrong Mortuary in Los Angeles, said that of the 27,000 burials he’s facilitated in the last 32 years, about 175 of them have been full body burials at sea. In 2020, 162 Californians were buried at sea, according to data collected by the Environmental Protection Agency.

“That’s not because people don’t want it. They aren’t aware you can have it,” said McKenzie, who prepared the casket for Woodburn’s burial. “They think it’s only for the military.”

There are many reasons why people want to be buried at sea. For some, the decision is financial: A sea burial including a coffin or custom-made shroud and boat rental might cost between $5,000 and $10,000, while a burial at a cemetery is at least $20,000, said Judah Ben-Hur, owner of Argos Cremation and Burials. (Having one’s ashes scattered at sea is even more cost-effective — around $2,500 for cremation services and to hire a boat to deposit them.)

For others, the decision is environmentally motivated. “There’s more acceptance that cemeteries take up a lot of space and that, ecologically, there are better forms of body disposal than a cemetery,” said Natasha Mikles, a professor of religion at Texas State University who is writing a book about death rituals in the time of COVID-19.

Some people want to be buried in the ocean because it’s a place that brought them joy. Woodburn loved going to the beach for picnics and to gather shells, Stremcha said. Ben-Hur has buried former scuba divers and fishermen, as well as people from other parts of the country who always felt drawn to the Pacific.

Even if you don’t have a particular affinity for the sea, an ocean burial can be deeply symbolic, said Olivia Bareham, a death midwife and founder of the Sacred Crossings Institute and Funeral Home in Los Angeles. She started doing sea burials 10 years ago.

“I hear things like, ‘I like the idea of becoming a drop of rain one day, and if I’m in the ocean, I can become rain on the mountaintop,’” she said. “If we think we are a drop in the ocean of bliss, it makes sense to return to the ocean.”

Burials at sea also provide a sense of ritual that may be especially appealing to people who are not affiliated with a religious institution.

The boat ride to the burial site serves as a transition to sacred space. The endless expanse of ocean conjures up the idea of eternity. And after the body goes into the sea, most captains circle the area counterclockwise three times to symbolize time standing still as loved ones say their final goodbyes and throw flowers into the water.

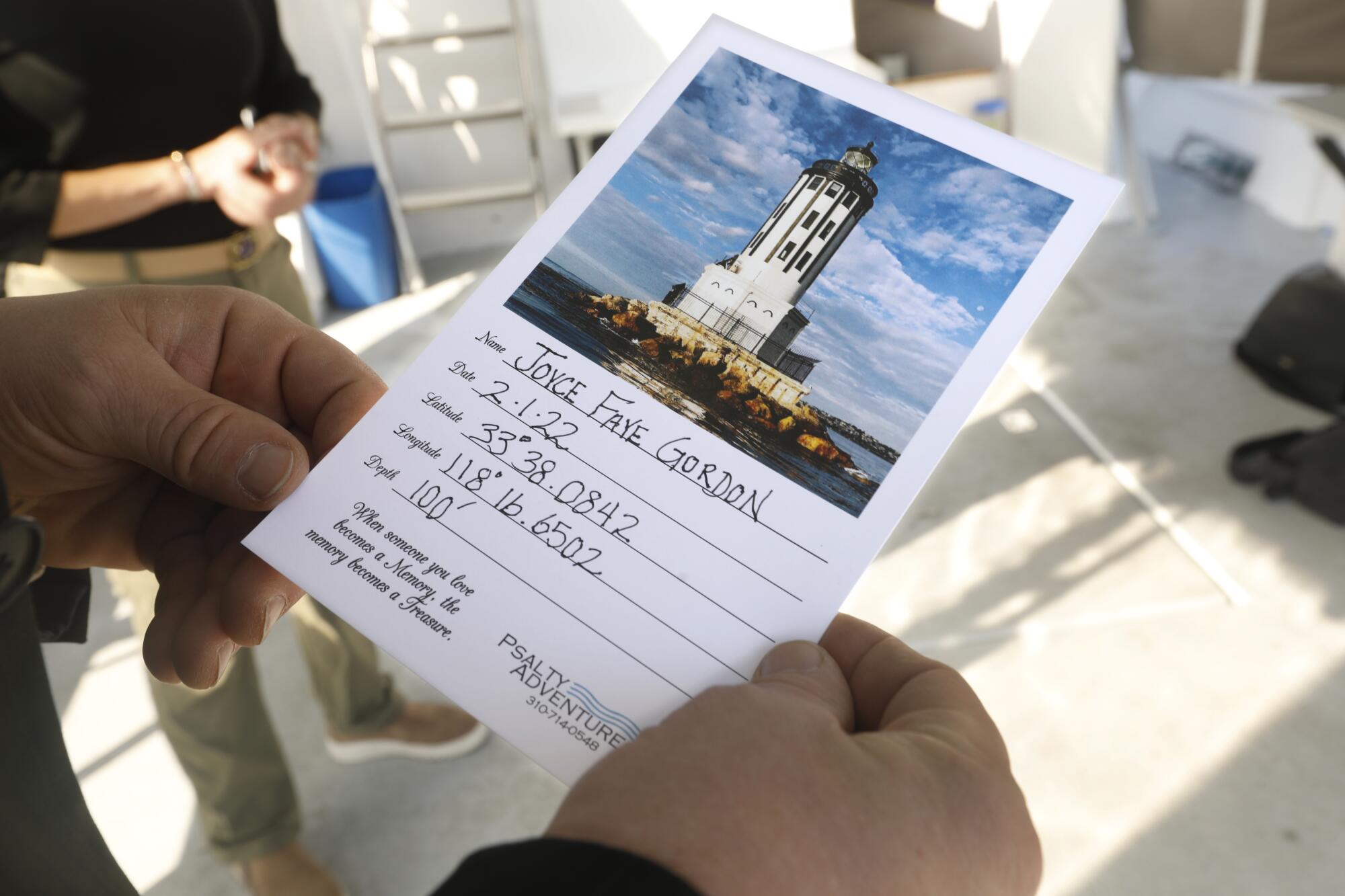

When the boat returns to shore, families generally receive the exact coordinates of where their loved one was deposited so they can visit the spot again.

Some of Bareham’s older clients still think their loved ones need a physical space to go to remember them — a headstone, a plot in a cemetery. She thinks the younger generation is waking up to what she calls the “ridiculousness of owning a piece of property for 1,000 years.”

“In this digital age, it makes more sense to have coordinates than an actual physical space,” she said.

It was environmental concerns that led 73-year-old sailor and community activist John Berol to have a burial at sea on April 1.

“As a professional boat captain who has sailed around the world, I’m a semi-radical environmentalist,” said his wife, Diane Berol. “I said to John, ‘When we die we have to do the most ecological disposal of our bodies as possible.’”

She and her husband decided against cremation because it didn’t feel ecologically sound. “Cremation requires burning and that puts CO2 in the air, and that’s not OK,” she said. “We wanted to make the best decision for the future of life on the planet.”

Diane has the exact longitude and latitude of where her husband’s coffin entered the ocean. When her time comes, she intends to be laid to rest in the same spot.

Anyone can be buried at sea as long as the burial occurs at least three nautical miles from shore and in at least 600 feet of water, according to federal regulations.

If a person wants to be buried in the ocean without a casket, the EPA recommends the body be wrapped in a biodegradable shroud and weighted, to ensure it falls quickly to the ocean floor and stays there.

“The last thing you want is to have the body of your loved one bobbing up and down on top of the ocean,” Ben-Hur said.

If a casket is being used, stainless steel is best, with all plastic materials removed. It should have 20 2-inch-wide holes drilled into it to allow water to flood in and weigh it down, and it should be secured with metal bands. Additional weights (sand or cement) can also be used to offset the buoyancy of the body.

Most boats that perform burials at sea have a platform on the back so pall bearers, or the crew, can easily push the casket or the shroud into the water.

Advanced permission is not needed for a burial at sea, but the EPA does need to be notified within 30 days of the service.

Putting a casket in the ocean may seem like littering, but McKenzie, who also plans to be buried at sea, doesn’t see it that way.

“We take old ships and put them to rest at the bottom of the ocean, and that starts an ecosystem,” he said. “Caskets do that too. They become a reef. It doesn’t matter whether you are in the earth or in the sea, we all go back to where we came from.”

Milton Love, a research biologist at UC Santa Barbara who studies the marine life that congregates around oil rigs, agreed that a submerged casket would become habitat for ocean animals, but whether that’s good for the environment depends on your point of view.

“Things that like to live on hard habitat like coral or sea anemone will be happy, but if the casket lands on mud you might not be so happy if you are a worm or a crab,” he said. “Personally, I don’t think it’s a great idea to throw stuff into the water.”

A body encased in a shroud would have less impact on the environment, especially if it was not embalmed, he said, but it will take a while to degrade.

“It would depend on where the body was situated,” he said. “Low oxygen levels and low temperatures could slow the decaying process.”

Most embalming fluid is made of formaldehyde, which is not great for marine life, but Love said it wasn’t a huge worry.

“There is a local effect, but the ocean is a big place, and dilution is a very big factor,” he said.

Mikles, the Texas State University professor, said most of the world’s religions allow burial at sea, “but usually only in extreme situations where there is no other choice for what to do with the body.” For example, if a sailor dies at sea and bringing the body back to land is not feasible.

Wedding rituals change quickly and are often influenced by what’s new and hip, she said. Funeral practices tend to be more conservative. However, as fewer Americans are affiliated with religious institutions than ever before, there is more freedom to remake the funeral experience.

“My mother wants to be turned into a diamond, my dad wants to be buried in something that turns into a tree,” Mikles said.

A week before her death from cancer last fall, Regine Verougstraete lay in bed as her close friend Kato Wittich read through the burial options on the Sacred Crossings alternative funeral home website.

Verougstraete wanted her body to remain at home for a few days after her death to give her family time to say goodbye, but she hadn’t decided what would happen after that.

“When she heard about full body burial at sea, her eyes just lit up completely,” Wittich said. “She loved the ocean. She was always willing to go into the coldest oceans and she always came out radiant.”

Verougstraete liked that a biodegradable shroud would not harm the environment or use up precious resources. And the full body piece was important to her too. She was diagnosed with breast cancer 15 years earlier and had gone through chemo, radiation and several surgeries.

“For Regine, knowing her body was going into the sea intact, after it had been so cut up and hurt, that was very important to her,” Wittich said.

Nine days after her death, 20 of Verougstraete’s friends and family sailed out of San Pedro Harbor to bury her body, then wrapped in a white shroud and surrounded by flowers.

After about an hour the boat stopped, and a simple funeral service began. A few people spoke. Odeya Nini, a performance artist and singer with a deep, haunting voice, sang about returning to the water. As she sang, Verougstraete’s loved ones tipped her body into the sea. After getting permission from the captain earlier in the day, one of her sons jumped in after her, his warm body hovering over her cold one — a final goodbye.

Wittich remembers feeling that her friend was now becoming part of everything. And now every time she goes to the ocean, she knows Verougstraete is there.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.