Help or handcuff? LAPD officers often delay providing medical aid after shooting people

After Olivio was shot, it took more than six minutes for officers to approach him. When they did, they put him in handcuffs.

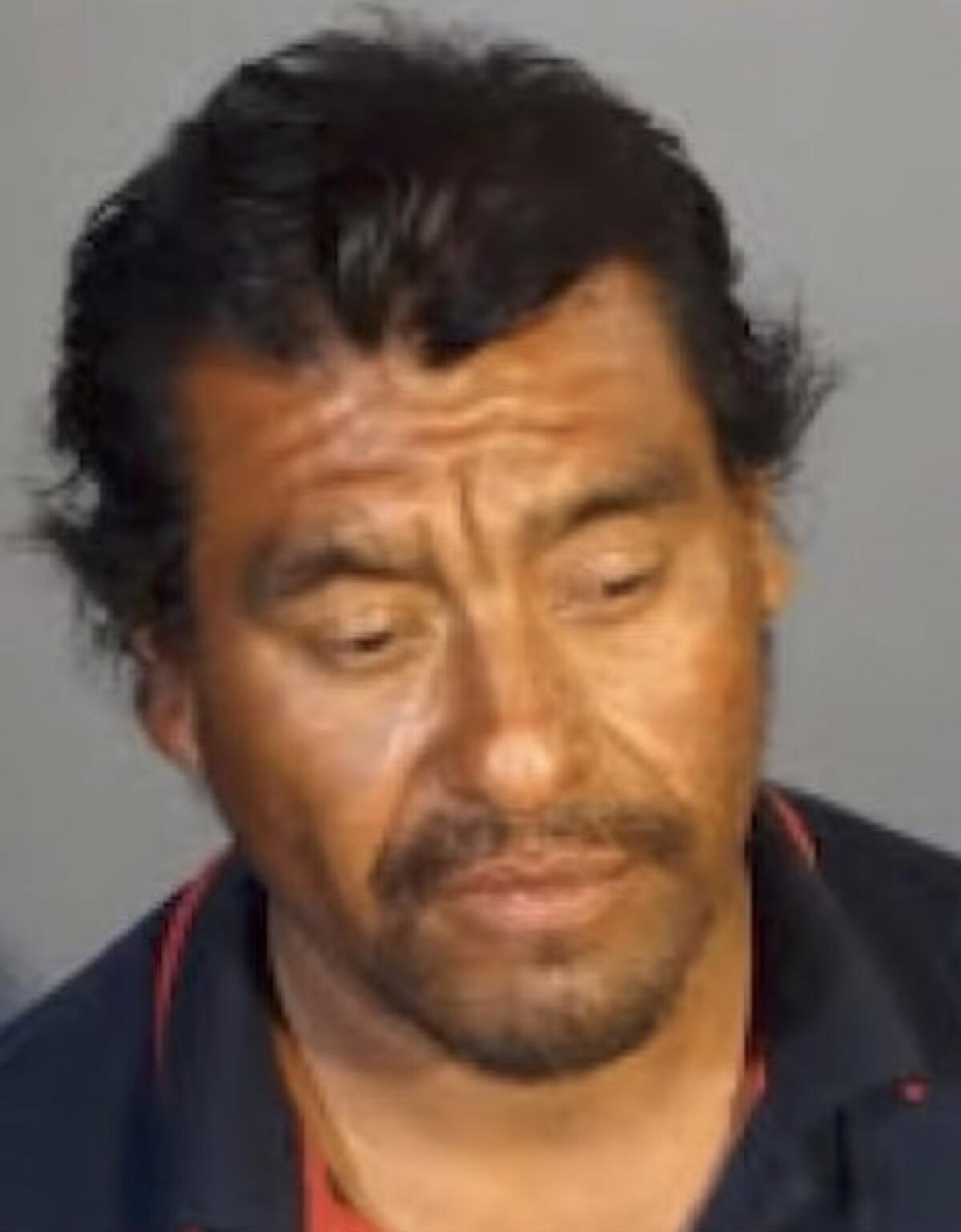

By the time a group of Los Angeles police officers cautiously approached Rosendo Olivio Jr. with guns drawn, more than six minutes had passed since they’d shot him.

Officers had confronted Olivio on a porch as the 34-year-old, seemingly in the grips of a mental crisis, held up a small knife and claimed to have doused the building behind him in gasoline, according to video from cameras worn by the officers. When he moved forward, imploring the officers to shoot, they did.

Olivio turned away and crumpled facedown on the steps. Officers screamed at him to “drop the knife!”

Blood pooled beneath Olivio as the minutes ticked by. Eventually, about 10 officers approached, their weapons trained on his motionless body. Two of them grabbed Olivio by the ankles and dragged him down the stairs. The knife fell from his hand as his face bounced off the last step.

They pulled his arms behind his back, handcuffing him. Video shot by a witness captured four officers carrying him through the street by his arms and legs. Paramedics later pronounced him dead.

The incident was a stark example of how LAPD officers — like police around the country — are trained to view people they’ve just shot as ongoing threats. The result is that officers routinely wait several minutes before approaching those suspects, then focus on handcuffing and searching them, often delaying medical attention or taking no steps to give any until paramedics arrive, a Times review of nearly 50 LAPD shootings and hours of associated video found.

Officers who did not provide aid — pressure on the wound, CPR or other measures — after some shootings were not punished, despite a department policy requiring them to assist those injured if they are able, according to the review. LAPD officials determined instead that discussions about the lapses and retraining on the department’s policies were preferable.

Most Los Angeles police officers found to have wrongfully opened fire on people in recent years avoided serious discipline or received none at all, according to a new report.

Police officials say that officers must ensure their own safety when dealing with potentially dangerous suspects, and that doing so can take time depending on the circumstances of each encounter. Officers say they sometimes fear making a person’s injuries worse if they try to intervene.

But Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, which advises police departments on policy matters nationwide, said rendering aid after shootings should be a “guiding principle” for police departments not only because it can save lives, but also for the impact it can have on the public’s perception of police.

“Part of being a professional cop today means being able ... to quickly pivot and recognize that you have a responsibility, if your department really believes in the sanctity of human life, to do everything humanly possible to get that person aid immediately,” Wexler said.

LAPD officials often spend a year investigating shootings by officers, analyzing second by second an officer’s actions in the moments leading up to the shooting and each pull of the trigger. Less attention is paid, however, to the minutes after the shooting, The Times found.

The Times had access to videos recorded by officers’ body-worn cameras or surveillance cameras in all but one of the 47 shootings in which LAPD officers struck someone since the start of 2020. The Times also reviewed detailed LAPD investigative reports available for 25 of the shootings.

Police officials say such weapons represent real, imminent threats. Others claim the danger is exaggerated and that officers are too quick to pull the trigger.

All the videos were edited by the department before they were released and often excluded portions of time during the encounters. However, they usually captured and included time stamps for when the officers opened fire and when they handcuffed the person they’d shot.

In some cases where officers fired on a suspect at close range, they had the person in handcuffs within seconds. In other cases in which officers feared the person might still be armed, according to available video, they didn’t approach them for more than 10 minutes.

On average, 3 minutes and 40 seconds passed before officers reached the person they had shot in the 39 shootings in which it was possible to time their response, The Times found.

The suspect appeared to be unconscious by the time police reached them in 22 of the shootings, and was at least partially incapacitated in the rest, the videos show. And in all but one of the shootings, the person was handcuffed after being turned over onto their chest or moved in other ways that experts say could have exacerbated their injuries, video showed. In some cases, they were then left facedown or simply held on their side for several more minutes as officers waited for paramedics, The Times found.

In one video, LAPD officers shot a man holding a knife, then Tasered him as he laid on the ground in an attempt to make his arm jerk farther away from the dropped blade.

“Don’t move!” an officer screamed at the man, who was not moving.

In another incident, a team of officers trailed a mentally ill man who was holding a hammer for several blocks through Westlake before surrounding him with their guns drawn. When the man, Samuel Ponce, threw the hammer in the officers’ direction and then raised another object in his hand, one of the officers shot him in the head.

After Ponce was shot, officers left him on the ground without providing care for more than four minutes, until they were ordered to start chest compressions.

An edited compilation of body-camera videos the LAPD released showed Ponce throwing the hammer and getting shot in slow motion, then cut to a supervisor instructing officers to start performing CPR — giving the impression the aid was swift.

A report on the shooting released months later gave a fuller account of what happened. Officers first handcuffed Ponce and rolled him onto his side to search him for weapons, and one officer poked him in the back, saying, “Hey, amigo.” No one checked his pulse or whether he was breathing, the report noted. The officers then left him facedown on the ground for nearly two minutes. After eventually checking him for injuries, they again left him on the ground without tending to him.

The officers didn’t start chest compressions until ordered to do so more than four minutes after the shooting.

One of the officers later explained his thinking to investigators. “I don’t want to just start doing, let’s say, like just random chest compressions if we don’t see where exactly he was hit and where he was injured, because you don’t want to just make the injury worse,” he said, according to the report. “So, we roll him over just so he can get better oxygen. I don’t know if at that point somebody did see where he was shot or try to put pressure on it, but compressions were started.”

Videos from LAPD body cameras show a group of officers slowly trailing Samuel Ponce for several blocks last month, firing hard foam projectiles at him. After Ponce threw a hammer and lifted a second object, an officer opened fire.

While the officer’s decision to shoot Ponce was found to be justified, LAPD Chief Michel Moore ruled the officers had not properly cared for him afterward. In an internal report on the shooting, Moore wrote that his “expectation is that they would have kept Ponce in a recovery position after he was handcuffed, holding him in place if necessary, before initiating CPR.” Moore was referring to turning a person on their side to help keep their airway open.

Moore directed supervisors to discuss Ponce’s treatment after the shooting with the officers, but did not recommend they be punished.

In its review, The Times found that detailed protocols related to officer safety were consistently followed after shootings, while the department’s more vague mandate to render aid was not.

Crucial minutes

After someone is shot, “time is really of the essence,” said Dr. Kenji Inaba, chief of trauma and surgical critical care at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center. “There are limited but effective things that can be done in the field, and the sooner they can be done in these specific situations, the better off the patient will be.”

Inaba, a reserve LAPD officer and the department’s chief surgeon, consults on the care for injured officers and advises the LAPD on medical training for officers. He also helps lead the Stop the Bleed campaign, a national initiative teaching first responders the importance of stopping blood loss for gunshot victims in the field.

Wounds from handguns — which account for the vast majority of shootings by police and others in Los Angeles — are typically best treated in the field by putting immediate, direct pressure on the wound, Inaba said. Applying a tourniquet and applying pressure, part of officers’ training, or packing the wound with gauze or cloth could also help in some situations, he added.

Luann Pannell, the LAPD’s director of police training and education, said that in line with state law, all police recruits receive more than 20 hours of first aid and CPR training, “to be able to provide a basic medical response until emergency medical services can arrive on scene.”

All officers are also issued a trauma kit and those working patrol assignments must get refresher training on CPR and the use of defibrillators every two years, Pannell said.

The fact that ambulances often arrive at shooting scenes quickly in L.A. does not mean police do not need to treat someone after a shooting, Inaba said. People can die from blood loss within minutes, he said, and for those who survive, blood loss complicates their treatment and recovery.

Policy vs. practice

Under the LAPD’s use of force policy, officers are expected to “render aid” to people they have shot “to the extent of the officer’s training and experience” and “to the level of equipment available,” including by using basic first aid, CPR or automated defibrillators.

The policy, however, does not specify what steps officers must take to comply with the order. The vague wording has allowed police officers to respond in vastly different ways after shootings, and police officials to judge those actions differently from case to case, internal LAPD reports on police shootings and videos showed.

Officers initiated chest compressions a handful of times, including one who, after detecting a faint pulse in a woman who had just been shot, revived her on a sidewalk before paramedics arrived.

In other cases, however, officers appeared to do little other than place the person who was shot on their side, without applying pressure to their bullet wounds or providing any other direct medical care.

Officers were found to have acted appropriately in some cases simply by calling for an ambulance. In other cases, including the shooting of Ponce, it was determined that officers did not do enough to help someone they shot, but they were not disciplined.

On the same day Ponce was shot in March 2021, a man named Nathan Glover crashed a car into a home during a police pursuit and then was shot by an officer who said he saw Glover holding a gun as he jumped from the vehicle. A gun was recovered at the scene.

Video released by the department showed the officers screaming at Glover not to move as he moaned in a patch of grass at the side of the home.

“I’m dying,” Glover said.

“The ambulance is coming, man. Relax,” one of the officers replied, before the officers moved forward and handcuffed Glover behind his back.

According to a later investigative report, Glover was then left on his chest for almost five minutes as the officers waited for paramedics. One of the officers told investigators that “he did not want to place Glover in a seated or recovery position as he did not know if Glover had suffered a lower-body or back injury.”

After Glover was shot, he was pulled from the grass and left on his chest without care for almost five minutes, until paramedics arrived.

Moore later found that the officers had broken policy for failing to do more. But rather than recommend they face some punishment, he opted again to make the poor medical response “a topic of discussion.”

Wexler said that it can be difficult for officers to suddenly start treating a threatening suspect as a victim in need of care, and that peer pressure among officers to continue treating suspects as threats can be strong. Those challenges, he said, make it more important for departments to train officers well on the rules — and then enforce them.

“This shouldn’t be left to the judgment of the officers to decide what ‘rendering aid’ means and under what circumstances” it is required, Wexler said. “To make rendering aid real, I think you have to put a lot into it. It can’t simply be an empty slogan.”

While there is no policy requiring officers to handcuff a person they shoot, they are taught to approach suspects carefully, often as a group with shields and weapons at the ready. Officers are also expected to formulate a plan for who in the group will handcuff and search the suspect, the department said.

Even when a person “appears to be incapacitated, the fear of the suspect re-arming himself, or even gaining consciousness and continuing hostile actions remains a possibility,” the department said in the statement.

In the more than 40 police shootings reviewed by The Times, none involved a person regaining consciousness or suddenly reaching for a weapon after being shot. Most who were conscious complied with officers’ orders, while a few resisted being handcuffed.

Some medical and policing experts faulted the LAPD — and police departments generally — for failing to properly train officers on how to treat those they’ve just shot and to instill in them a sense of duty to try to save their lives.

“It’s not the ethos,” said Christy Lopez, a Georgetown Law professor and former deputy chief in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. And that “signals something really corrosive to community members.”

The message is particularly acute for family members of people who have been shot by the police.

“They could have been more careful with him. They could have respected his body. But they didn’t do none of that,” said a relative of Olivio, who requested anonymity for fear the police would retaliate against her for speaking out. “They treated him like an animal, and he wasn’t an animal. He was a human being.”

The LAPD, which is still investigating Olivio’s shooting, has not identified all of the officers involved, but has named the two who opened fire: Faviola Salinas and Kyle Locke.

David Winslow, an attorney for Salinas and Locke, declined to make the officers available for questions from The Times, but said that they had followed their training in a difficult situation.

Winslow alleged that Olivio was a gang member in gang territory, and that a hostile crowd of people had gathered after the shooting — increasing the risk to officers and complicating the medical response, in part because paramedics “did not want to go near that apartment.”

And while Olivio may have been unconscious, the officers couldn’t be sure, Winslow said.

At Olivio’s viewing at the Funeraria Latino Americana in East L.A. in January, mourners could still see the wounds to his forehead, nose and lip from when his face bounced off the steps the day he died.

They were still there despite the mortician’s makeup and his mother’s attempts to hide them.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.