Column: A search for answers to anti-Asian violence

William Yu, 46, is healing from the multiple stab wounds he suffered in Chinatown earlier this month at the hands of a random attacker. But the incident has already left scars on the way that he and his family see themselves, said his brother David.

Now he cannot stop thinking about the bystander who did not intervene, a man in a hoodie riding a bike who watched his brother struggle with his attacker for nearly half an hour. He wonders if his parents should be taking walks at night. After he drops his wife off at work, is she safe to walk to her building?

“Prior to this I didn’t feel the whole Asian hate component. It wasn’t affecting me or anybody I know,” Yu said. “Now it’s like, there is a bit of fear and anxiety. What’s going on?”

Yu isn’t alone. A survey released last week by the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs finds that 1 in 4 Asian Americans surveyed in Los Angeles said they have experienced a hate incident since the pandemic began. And a new online poll by the research firm AAPI Data found that 1 in 6 Asian Americans nationwide experienced race-based violence in 2021.

And last week, I wrote about Yongja Lee, 65, a Korean American liquor store owner in Long Beach who was stabbed in the neck and is now paralyzed from the neck down.

A flood of racist invective lobbed from a presidential pulpit at the start of the pandemic triggered a rash of street violence and open hostility toward Asian Americans. The violence has reached Asian Americans of all stripes: immigrants, their children, Republicans, independents, Democrats — anybody who could be mistaken for Chinese. It has sparked political reverberations in the Asian American community that will be felt for years.

Yu works with the homeless and mentally ill, and believes that they deserve compassion and help, not criminalization.

But “things are getting unsafe,” he said. “What would happen if my brother hadn’t fought back? I don’t care red or blue or who. We need to protect the residents of L.A. What’s going on is not really working.”

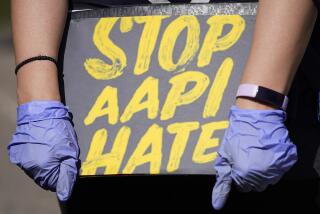

Because hate crime reporting is inconsistent, especially for those involving Asian Americans, it’s difficult to establish the scale and frequency of the violence. A survey by the group Stop AAPI Hate finds that as of December 2021, nearly 11,000 hate incidents have been reported.

Still, it is largely impossible to assess intent from video clips, and even Yu is not certain that his brother’s attacker was racially motivated. Authorities in Long Beach and Los Angeles are not investigating Lee’s or Yu’s stabbings as hate crimes.

But what’s obvious is the climate of fear that has taken root in Asian neighborhoods and communities, especially in dense urban areas where women and seniors walk or take public transportation. The Pat Brown survey found that 80% of Asian Americans felt that racial violence and hostility was a serious problem.

Bopomofo Cafe in San Gabriel, a boba shop flanked by a popular Vietnamese restaurant, a Shanghainese eatery and several other boba shops, should be a safe, familiar place for Asian Americans. But the violence had touched every person I spoke to there on a recent weekday afternoon.

“It’s so much more expensive, but I’ll take Ubers way more often now, even for short distances. I avoid walking. It’s just really stressful deciding how to get places.” said Suzie Lee, 27, who was visiting from New York City.

“You expect things like name-calling and bullying, but now this is violence,” said Suzie’s friend H. Lee, 26, who declined to give her first name out of privacy concerns. “I want to be informed, but I just can’t keep looking at all these clips. It’s just really disheartening.”

Climbing into his pickup truck in the parking lot, Taylor Liao, 60, said he feels safe in the San Gabriel Valley, but he won’t ride the bus anymore and tries to stay in Asian neighborhoods.

“Obviously, it’s pretty bad right now with the economy is down. People think Asian Americans have more money, but they’re mistaken. It feels like there’s nothing we can do,” Liao said.

For Pauline Kim, 24, the attacks have spurred an ongoing conversation about race with her parents, Korean immigrants who came to the U.S. 30 years ago. Her mom has a habit of downplaying the family’s experiences of racism, but now Pauline makes sure to distinguish right from wrong. She tries to untangle their stereotypes about other races and convince them that they can stand up for themselves.

“Like, at a doctor’s office people get impatient with them and they brush it off or don’t advocate for themselves,” Kim said. “They think my parents don’t understand, but they do.”

Even if we accept that the motives of attackers in videos are unclear and hate crimes data are not ideal, the truth is that an entire generation of Asian Americans are learning to look over their shoulders.

And they are finding that racism doesn’t have an easy solution. Neither police nor policy can can stop racist sentiment. Yes, we should strengthen hate crimes laws and reporting so that they may serve as actual deterrents against racism. We should support efforts to improve representation and awareness about Asian Americans so that bystanders might be more likely to intervene when an Asian American is being attacked. There’s plenty that can be done to improve street safety in ethnic neighborhoods suffering from disinvestment. Teaching Asian American histories in schools could tilt us toward a more tolerant future.

But truly combating racism requires us to take on bigger political questions that we Asian Americans do not all agree upon.

How do we make safer neighborhoods for vulnerable Asian elders without attacking the gentrification that has emptied the neighborhood at night? How can we combat street crimes without understanding why crime exists in some neighborhoods but not others? How do we reduce random public attacks without solving the homelessness and housing crisis? How can we reject xenophobia without disentangling our patriotism from our nationalism?

These are quandaries for which there is no easy solution. And so there will not be a sudden end to the uneasy feeling that you are a target for reasons beyond your control. Now we have to learn to live with the fear that a geopolitical swing can paint people who look us as the enemy.

My advice is this: Don’t look away. Remember this feeling, and remember you and your loved ones have every right that every other American has. And remember that you are not alone.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.