Stolen, sold, not even solid gold. The story of the Oscar statue

Recognize this statue? [Shows picture of Michelangelo’s “David.”]

Nope? Well, how about this one? [Shows picture of the Venus de Milo statue.]

Ring any bells? Nothing? OK. [Sighs.]

How about this one? Yes, you’re right. [Finally.] That is an Oscar.

Perhaps the most recognizable if not artistically celebrated piece of statuary in much of the world does not depict a hero or god of antiquity.

It is, instead, a little metal man, a 24-karat-gold-plated homunculus devoid of hair, facial features and sex organs. It is swaddled in story if not in clothes.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

It was or wasn’t first sketched out on a Biltmore Hotel tablecloth. It was or wasn’t modeled on the body of Mexican director and actor Emilio Fernandez (probably not). It did or didn’t get the name for its supposed resemblance to the backside of Bette Davis’ first husband, Harmon O-for-Oscar Nelson (so why isn’t it a Harmon?), or because, most likely, it reminded Margaret Herrick, the librarian and then executive director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, of her mother’s first cousin, Oscar Pierce, a man she herself seems to have never met.

That the flippant nickname stuck to so august a trophy was a source of mortification to Mrs. Herrick. She wrote, in a 1959 letter to a Merriam-Webster dictionary editor, that she “regretted more times than I care to remember” a “thoughtless quip.”

“I have always felt that the Academy loses something in dignity every time the statuette is referred to as Oscar.” But she must have acknowledged that “Academy Award of Merit” was too unwieldy for headlines and too much of a mouthful for broadcasters, and “Oscar” too irresistible.

There are something over 3,000 of them out in the world somewhere — on mantlepieces, in trophy cabinets, anchored on shelves in earthquakey California. They have been stolen and lost, stolen and found, have turned up in a Pasadena flea market, a San Francisco pawnshop, and a Hollywood garage sale.

The Nobel Prize medal is rarer — something like a thousand of them awarded in 120-plus years, and made of actual gold — but not one person in a hundred would recognize Alfred Nobel’s dignified, bearded profile on the medal that bears his name, a medal no one has ever called “the Alfred.”

What a long, strange trip Oscar has had.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

First, the heists:

From the earliest Oscar statuettes awarded in 1929, they have been objects of lawless desire. The first known theft was from 7-year-old child actor Margaret O’Brien — a special juvenile Oscar award for her role as the rambunctious Tootie in the 1944 film “Meet Me in St. Louis.” Ten years later, as O’Brien’s mother was fatally ill, the family maid took the Oscar and two other awards home to polish, as she had done before. She never brought them back — in fact, she herself never came back.

In the early 1990s, the same little Oscar had no takers for $100 at a Pasadena flea market. When it showed up for $500 at a different Pasadena flea market two years later, two friends pooled their cash to buy it. They ended up returning it to O’Brien, who had been given a replacement Oscar but was thrilled to have the original back.

That theft was penny-ante compared with the “gold strike” of 2000. A metal salvager found 52 Oscars, still plastic-wrapped in their shipping crates, in trash bins behind a Koreatown store.

It’s a tangle of a story, as almost everything about Oscars tends to be.

The shipment of 55 Oscars from the Chicago manufacturer (the statues are now made in New York) vanished from a trucking company’s loading dock in the city of Bell. Willie Fulgear, the salvage man who found the 52, got a reward, much felicitous publicity, and a limo and tickets to attend the Oscars, where Billy Crystal saluted him from the stage.

Three men were sentenced in connection with the theft. They’d evidently planned on selling the statuettes but presumably dumped the “hot” Oscars once the men got wind of the global publicity — and the serial number that each Oscar bears. (One or two of the three missing Oscars turned up in a federal drug raid in Miami, but at least one is still on the loose.)

One of the trio turned out to be Fulgear’s half-brother, but the brothers had been on the outs for years, and the connection between theft and discovery was happenstance. What became of Fulgear thereafter is another story but, alas for him, not one that was bought for a film, as he’d been told it would be. Welcome to Hollywood.

In 2002, Whoopi Goldberg sent her best supporting Oscar, for “Ghost,” to the academy for replating and a polish, but it got lost between L.A. and the Chicago company that crafts and tends the Oscars. Someone intercepted it, took it out of its shipping package, and sent the empty container along to Chicago. The Oscar was found by a security guard in a trash bin at Ontario Airport. “Oscar,” said Goldberg, “will never leave my house again.”

Hattie McDaniel won the Academy Award in 1940 for supporting actress for her “Gone With the Wind” performance, the first-ever academy prize for a Black performer. Before 1943, supporting actor awards were plaques, not Oscar statuettes. McDaniel bequeathed hers to Howard University, whence it disappeared from sight in the early 1970s, perhaps stuck away in some overlooked storage box.

In 2018, Frances McDormand’s second best actress Oscar, for “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” was snatched right off the table where she had set it next to her at the official after-party. A photographer saw a man hefting the statuette and stopped him and relieved him of the Oscar.

The man accused of taking the Oscar, Terry Bryant, had had enough time to post a Facebook boast video of himself captioned “My Oscar baby.” He hoisted it and said, “My team got this tonight. This is mine,” and smooched the statuette. Charges were dropped when prosecutors said they couldn’t go forward and Bryant’s attorney said the man never intended to keep the statue. Bryant’s Aug. 22, 2019 Facebook post read, “Oscars Case DROPPED AND DISMISSED TODAY!!! ~ because i did not do what they said i did ! WE WON BECAUSE IM 100 % INNOCENT ! TO GOD BE ALL THE GLORY HALLELUJAH !!! GOD DID IT !”

One disappeared right before the eyes of some of the most famous people in the world — snatched right off the Oscar stage when it was darkened for a commercial break.

As former academy director Bruce Davis wrote in the Wrap years later, the 1972 documentary “Marjoe” had won, but only one of the two directors came onstage to carry off their statues. The second one was left onstage at the podium, and when the lights came back on, it had vanished. What a screenplay that would have made.

Davis followed the thread on that Oscar, and the one that Marlon Brando refused for “The Godfather.” The Native American woman he sent onstage to read Brando’s denunciation for the treatment of Native Americans on film and in real life never so much as touched the Oscar. Actor Roger Moore held on to it instead onstage and took the Oscar home with him, and the academy sent people to pick it up. How that Oscar crossed paths with the missing best documentary Oscar is just another layer in the Academy Award legend. That’s entertainment!

Oscar’s first rejection was from Dudley Nichols, the screenwriter for the 1935 film “The Informant.” He was making his feelings known about the academy’s refusal to recognize unions like the screenwriters’ guild. Twice, as the story goes, the academy shipped him his statuette, and twice he sent it back. He accepted it a few years later, after the feds recognized the guild.

For the record:

7:19 p.m. March 28, 2022This article gives the incorrect title of a 1935 film, for which screenwriter Dudley Nichols refused an Oscar, as “The Informant.” The correct title is “The Informer.”

It was the ceremony itself that revolted actor George C. Scott — “a two-hour meat parade, a public display of contrived suspense for economic reasons,” he called it. When his name was announced onstage by presenter Goldie Hawn for his 1970 portrayal of the World War II general in “Patton,” Scott was in New York, watching an ice hockey game before going to bed. The film’s producer accepted it onstage, and returned it to the academy per Scott’s wishes. (Scott once told TV Guide that he’d asked that his Oscar be sent to the Patton Museum in the California desert where Patton did tank maneuvers, but that was never put in writing.)

In 1982, The Times wrote that Scott had at last shown up for the ceremony — he wasn’t nominated — and was spotted by the indefatigable Variety columnist Army Archerd, who called out after him, “Your Oscar is waiting for you at the Academy! Wilshire and LaPeer!”

General Motors? Big Oil? Big Rubber? The demise of L.A.’s streetcars stemmed from public policy and our own appetite for automobiles.

How much is an Oscar worth?

As much as a million five, the price Michael Jackson paid for the “Gone With the Wind” best picture Oscar.

Or a buck.

Since 1950, Oscar winners have had to agree in writing not to sell off the little man on the open market without first offering it back to the academy for $1. For a time, the price seems to have been $10, but $1 was fixed as an unquestionably token amount.

This has messed up the plans of Oscar winners’ heirs and others who managed to get their mitts on the real thing. Actress Vivien Leigh won two Oscars, and one, for “A Streetcar Named Desire,” was stolen from her home in 1951. But it was her first Oscar, for “Gone With the Wind,” that was put up for auction by her family in 1993, and it sold for a then-record $510,000. Joan Crawford’s best actress award, for the 1945 film “Mildred Pierce,” was sold in 2012 for $426,732.

In 1999, Michael Jackson bought the best picture Oscar for “Gone With the Wind” at auction for a still-record $1.54 million. He died unexpectedly 10 years later, and the Oscar that presumably gleamed somewhere in Jackson’s Neverland ranch home disappeared before the estate could auction it off. Another one missing in action.

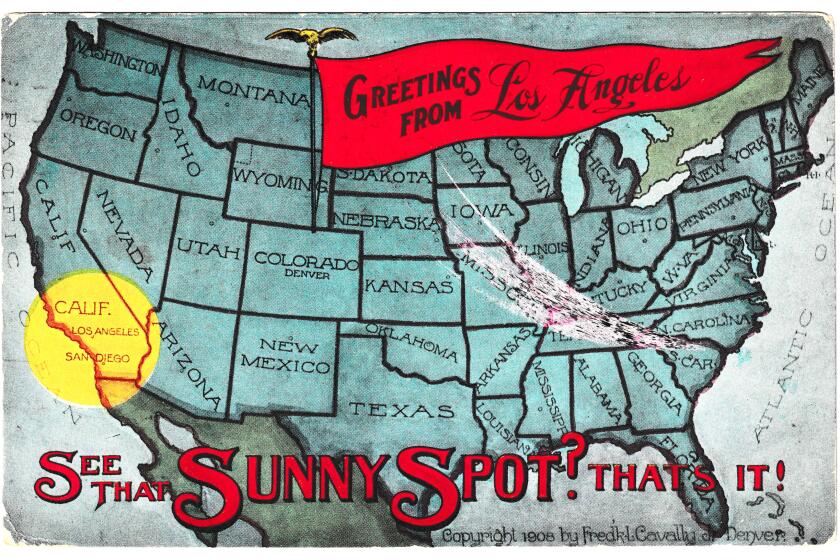

Sunny and mild L.A. winters have long been used to sell our town to frigid Midwesterners and Easterners, attracting the sick, the farmers and the moviemakers.

But the academy decided that even older Oscars might fall into its $1 buyback category if early winners were still academy members after 1950 and could still be bound by the new rules.

There have been some unappetizing public court cases. The academy was able to stop Beatrice Welles, the financially distressed daughter of actor/director Orson Welles, from selling her father’s Oscar for the screenplay for “Citizen Kane” for a time, but in the end, she was able to sell it.

But heirs of the second wife of Buddy Rogers, an actor and musician and third husband of pioneering silent actress Mary Pickford, were barred from selling Pickford’s 1930 best actress Oscar, even though the proceeds were meant for charity. A judge found that that Academy Award belonged to the academy under the first-refusal rule.

In 2006 an online casino made an end-run around the no-sale rule. Instead, it bought a 999-year lease on the 1960 best score Oscar won by composer Morris Stoloff for “Song Without End.” The Canadian company intended to send the Oscar on tour with a traveling show of Barnumesque curiosities like Britney Spears’ pregnancy test and William Shatner’s kidney stone — exactly the kind of cheesy exploitation that the academy’s ownership rules were meant to stop.

Only once, to anyone’s knowledge, has an actual Oscar winner sold his Oscar, and on this occasion the academy wisely backed off rather than go to court against a disabled World War II veteran.

The Oscar winner was Harold Russell. He lost both hands in the war, and was cast as a returning soldier in the 1946 best picture “The Best Years of Our Lives,” about servicemen returning from the war. Russell won the best supporting actor Oscar and a special Oscar “for bringing inspiration and hope to war veterans.” He was selling the best actor Oscar in 1992 to pay his wife’s medical bills. He turned down the academy’s offer of an interest-free loan in exchange for the Oscar because he said he worried about being able to repay it. The auction brought him $55,000. (It was said that uber-agent Lew Wasserman bought it and donated it to the academy,. Director Steven Spielberg did the same for two of Bette Davis’ Oscars and one of Clark Gable’s, writing checks for something like $1.3 million to keep them in academy hands.)

Remember that yard sale Oscar I mentioned? On a spring Saturday morning in 2007, at a two-story house up in the Hollywood Hills, amid the crystal and china for sale, there it was, an Oscar-ornamented plaque awarded to Joseph Schildkraut as best supporting actor in 1937 for his portrayal of the persecuted French army officer Alfred Dreyfus in “The Life of Emile Zola.” His widow was selling it for $150,000, but even the most dedicated yard-salers wouldn’t be carrying that kind of cash. So the Schildkraut Academy Award ended up selling at auction in 2013 for $92,866.

The statuettes you see handed out onstage during the ceremony are blank; no one can take a backstage peek to see who the winners will be until those envelopes are opened. Afterward, at the Governors Ball, winners take their statuettes up to a station set up in the ballroom where pre-engraved plaques with the winners’ names and details are affixed to the blanks.

Much care, as you imagine, is taken with secrecy and accuracy in the Oscar engravings. In 1938, when Spencer Tracy won best actor honors for “Boys Town,” he agreed to donate the award to the Nebraska home for distressed kids if the academy would send him a replacement. It did: engraved with “Best Actor — Dick Tracy.”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.