Column: This 101-year-old surgical pioneer still works every day. And he’s not about to retire

When Dr. Bruce Gewertz arrived from Chicago 16 years ago to work at Cedars-Sinai, he took note of his new neighbor.

“When I moved in,” said Gewertz, Cedars’ surgeon-in-chief, “there was this 85-year-old guy in the office next to mine and I thought, ‘Well, how long can that last?’”

At this point, there’s no telling.

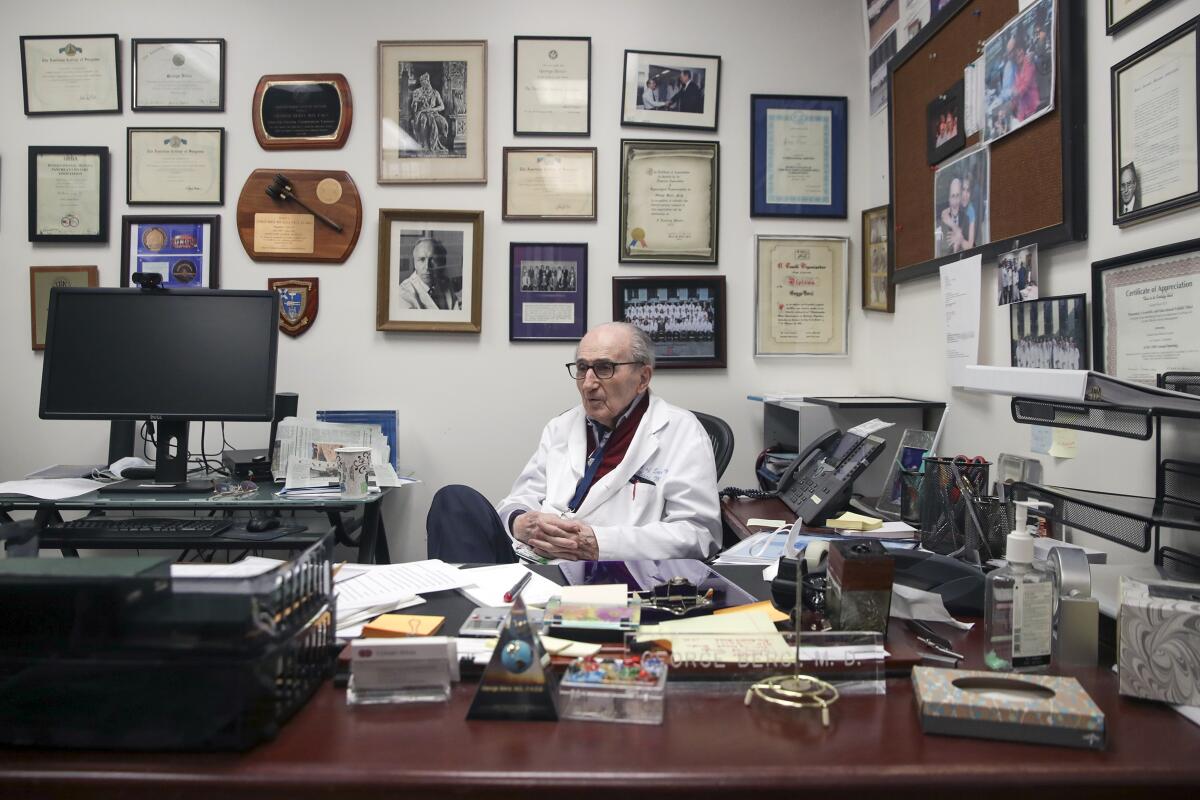

Dr. George Berci, a Holocaust survivor and a pioneer of surgical technique, is still in the office next door.

And last week, he marked his 101st birthday.

“Until COVID,” Gewertz said, “it was not uncommon for me to come into the office at 7 a.m. and find George already here working. And his achievements in the last 20 years of his life are probably as important as in the first 80.”

Berci got to work at 7 a.m. Tuesday and had a couple of meetings on the docket. He told me he reports to the office about two days a week now, and works from home the rest of the week, answering queries from other doctors and checking in with colleagues around the world.

Just looking at him, there isn’t much physical evidence that Berci is in his second century. The shoulders have rounded a bit, but he walks at a good clip (in snappy two-tone wingtips), ducking through secret passages of the hospital to get to here or there. His eyes are clear, his mind sharp.

Spending $800,000 for a single unit of homeless housing? L.A. has to do better

Part of that is just plain luck; by some combination of genetics, lifestyle and circumstance, certain people age more slowly. And part of it is a reenergizing potion of passion and purpose.

Berci puts on the white lab coat and goes to work because the job he loves is not done.

But to be perfectly honest, he was not in the best of spirits when we met. The news out of Ukraine was both horrific and haunting, given Berci’s own suffering at the hands of brutal dictators.

“I hope it will somehow improve,” said Berci, who recalled the German and Russian aggression that tore families apart in his day and cost millions of lives.

“We have to help them,” he said of the Ukrainian masses who have fled their smoldering country.

Born in Hungary and raised there and in Austria, Berci was forced into a labor camp with fellow Jews in 1942 and endured the misery of grueling manual labor while nearly starving to death. Two years later, during the bombardment of Budapest by Allied forces, Berci’s labor camp guards were distracted long enough for him and other prisoners to escape. Berci went to work in the Hungarian underground, risking his life in an operation that created and delivered fake IDs to Jews in hiding.

When the war ended, Berci picked up the violin he had played since he was a lad and planned a career in music. But his mother waved a finger at that idea.

Berci’s father and grandfather had died, leaving the family destitute, so his mother put in a vote for something more financially promising than music. She wanted him to go to medical school.

Berci still loves music, but says he is eternally grateful.

He made surgery his specialty and was working at a Budapest hospital in 1956 when Russian forces crushed an anti-Communist uprising, killing thousands. Bloodied victims arrived by the hundreds at the hospital, and when the drama subsided, Berci began plotting a course out of Europe.

A fellowship took him to Australia, where he keyed on ways to improve surgical technique. His innovations came to the attention of Cedars-Sinai, which recruited him in 1967. There, he began developing endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques that are now in widespread use to diagnose and surgically treat diseases of the kidneys, colon and gallbladder — the list goes on.

In earlier times, a surgeon carved into the body. But with new sets of tools, the work is less invasive and performed through small incisions or orifices. Berci had studied mechanical engineering as a young man and helped develop the tiny camera used in these procedures, allowing surgeons a clear view inside the body as they work.

Berci has written dozens of books and scientific papers on all of this. He told me his latest book about the history of biliary surgery — “No Stones Left Unturned,” co-authored by Dr. Frederick Greene — was a labor of love that involved years of research.

Mental illness is a primary driver of homelessness in Los Angeles. We have the tools to make things better.

He is driven in large part, Berci told me, by a desire to reduce healthcare costs and reach more patients. Less invasive and more effective surgeries mean shorter hospital stays and faster recoveries.

“There is no doubt that his ideas and his work have changed the face of surgery,” Dr. L. Michael Brunt said in 2013 after producing a documentary on Berci’s life and career. The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons now has a lifetime achievement award in Berci’s name, even as Berci adds to his own achievements.

“He’s constantly attending all of our conferences and making cogent references, and he’s remarkable,” Gewertz said.

Berci’s current obsession is to educate the next generation of surgeons and their mentors on refining gallbladder surgery, so that all stones are removed and follow-up surgery is not needed.

“He’s put together a coalition of all the senior gallbladder surgeons in the country to make that an expectation of our training programs,” Gewertz said.

Berci’s daughter, Katherine DeFevere, said her father has always been able to rise “above the horrors and figure it all out. … He is the most resourceful person I have ever met, and he has the most amazing survival mechanism — this drive to survive and re-create yourself.”

But that can be challenging as you age, Berci told me. He is troubled and disappointed both by the state of the world and the degree of political division in the United States, and he is still mourning his wife’s death three years ago.

“If you’re alone, it’s a different ballgame,” Berci said, and though he still has his beloved Italian-made violin, “it doesn’t work so well with 100-year-old bones.”

But Berci gets out of bed at 5:30 a.m., and if he doesn’t go for a walk, he goes to a gym.

He watches what he eats. He does not drink. He follows the Lakers.

And he is still, at 101, always eager to get to work.

Any plans for retirement? I asked.

He responded flatly, as if the very notion was preposterous.

“The answer is no,” Berci said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.