Cal State pays millions to executives after they resign, with little oversight of what they do

As California State University students struggled under the pandemic and other hardships in recent years, the public system has paid more than $4 million in salary and benefits to a small group of former executives as part of a program to help with the “transition” after they step down from their posts, according to state records and interviews by The Times.

The latest to benefit from the perk of enrolling in the CSU’s Executive Transition Program is former Chancellor Joseph I. Castro, who resigned last month amid outcry over accusations that he mishandled sexual abuse and workplace misconduct allegations when he was president of Fresno State.

Others receiving payments under the program include a former San Jose State president who stepped down amid controversy over her response to reports of sexual harassment as well as Castro’s predecessor, according to interviews and a Times review of program records since 2015.

Following his resignation as CSU chancellor, Joseph I. Castro will continue to receive his $400,000 salary for a year and a housing allowance.

As part of the deals, former executives are entitled to full medical, vacation and other benefits and their salaries accrue toward their pensions, records and interviews show. Most of them have been guaranteed lifetime faculty positions, entitling them to additional benefits.

The transition salaries have typically been paid for a year and were for work such as providing “advice and counsel” to CSU administrators, according to the records. In one instance, the duties assigned to a former Cal State Northridge president who received more than $275,000 for a year were outlined in a single sentence in a public report, which said she had been available to provide input on “matters pertaining to the California State University.” But the program does not track what officials do while being paid.

Officials with CSU have said being able to offer the program helps recruit executives in a competitive market and ensures institutional knowledge is retained once university leaders step down from their posts. Executives must have worked at least five years in a qualifying position to be eligible for the program. The UC system has had a similar transition program that pays its top executives lucrative salaries and benefits after they step down.

“The executives that are doing this are theoretically retiring, but not separating from the university. They retired from those respective positions but chose to participate in this program, which is a benefit/perk of that executive appointment,” spokesperson Mike Uhlenkamp said.

More than a decade ago, a state audit singled out the program and its failure to document work performed by those enrolled in it, prompting CSU officials to agree to better track the program.

But pressed for an accounting of how the public money has been spent, Uhlenkamp acknowledged this week that there are no records detailing the number of hours worked by the former executives or what they did for the money.

After inquiries from The Times, the CSU said the Board of Trustees would review the executive transition program in the future.

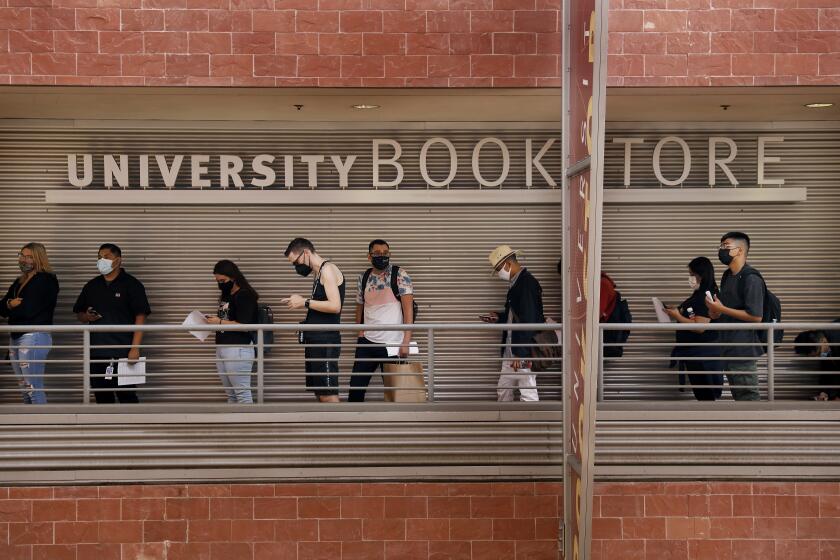

The payouts have been made during a period when undergraduate tuition increased by 5%, when admission caps were placed on entire campuses and when students across the largest four-year public university system in the nation struggled under the financial burdens of the pandemic.

About half of the approximately 430,000 undergraduate students in the system are Pell Grant recipients with exceptional financial needs and nearly a third of them are the first in their families to attend college, according to CSU data.

California State University is nearing its goal to increase graduation rates by 2025 but needs to do more work to close the equity gaps on campus between historically underrepresented students and peers.

In interviews, Cal State students questioned the justification for paying generous sums of money to top executives while students regularly face hardships.

“It’s a complete abuse of power,” said Cal State Fullerton student Ash Hormaza, 22. “As students, we’re constantly told that there’s not enough funding in the system for more mental health counselors or housing for students. Then I find out that there’s funding for former executives.”

Cal State Monterey Bay student Breanna Peterson, 29, who caught COVID-19 in 2020 while living with her high-risk parents, said many students and their families are barely making ends meet.

“A lot of students face homelessness and food insecurity — $200 for a textbook can make or break students financially,” she said. “We have students struggling in big ways.”

In the Cal State system, records show that a transition program was first established for Cal State executives in 1981 and has been modified three times over the years to expand the pool of eligible executives and change approval requirements, among other revisions.

After media reports in 2006 disclosed that the system had paid roughly $4 million over a decade to departing executives, the union representing CSU faculty filed a lawsuit and the state launched an audit of CSU compensation, including the Executive Transition Program.

The audit concluded a year later that there was lax oversight of the program, that agreements were brokered without public notification and that former executives were also allowed to take other paid jobs while receiving state compensation.

In the aftermath, Cal State officials reformed the program by preventing former executives from receiving transition payments while working other jobs and requiring the payouts to be reported in public sessions of the CSU Board of Trustees.

In their response to the audit, CSU officials also agreed to include a “report of accomplishments and deliverables” in annual reports presented to the trustees. Times reporters reviewed all board minutes, including annual reports, since 2015 and found that no such information had been disclosed. A second audit from 2017 found no existing procedures for how executives report their duties.

The program is currently available to presidents at the 23 campuses as well as the chancellor, general counsel and six vice chancellors at the system headquarters in Long Beach. All of them are among the highest paid administrators in the CSU, records show.

Since 2015, CSU records show, 11 former top officials have benefited from the program.

Under CSU policy, the chancellor negotiates and approves transition packages for presidents, and the chair of the Board of Trustees approves the package for the chancellor. Full board approval is not required, but records show that board members are informed of executives who enter the program, salaries and stated duties.

Salaries are calculated at the midpoint between an executive’s final salary and the maximum of the salary range for a full-time professor, which is typically lower.

In all but one instance since 2015, records show, the transition salaries continued for a year. The exception was former Chancellor Timothy P. White, who resigned in January 2021.

White is receiving an annual salary of $327,744 for two years until the end of this year. He also receives a $24,000 car allowance for the period and payment for any CSU-related travel costs and incidental expenses, according to his agreement, which was approved by board Chair Lillian Kimbell.

Under terms of the agreement, White “will be available to the board and the chancellor for advice, counsel and other duties mutually agreed upon.” He also co-chairs a task force for the American Council on Education and participates in “other activities in California and nationally that are related to public higher education.”

White also holds “retreat rights,” guaranteeing him a tenured professor position in the College of Health and Human Services at Cal State Long Beach when the program concludes.

In White’s executive transition agreement, Kimbell said he was also eligible to participate in an early retirement program for faculty, which could guarantee him full benefits even though he was teaching half-time. The program is available to all tenured CSU faculty who reach retirement age.

“This is handled on the campus,” Kimbell wrote, “so you will need to let the president and provost know to ensure you will be considered appropriately for a teaching appointment.”

White could not be reached for comment.

While serving as chancellor, White advised Castro, then-Fresno State president, as he was negotiating a secret settlement with a former campus vice president accused of sexual harassment, bullying and retaliation, according to Castro.

Weeks after the settlement was finalized, Castro was selected as CSU chancellor to replace White. Castro previously told The Times that he did not tell the board about the settlement or investigation, believing White would do so if he felt it necessary.

In recent weeks, former trustees confirmed that they were unaware of the settlement prior to selecting Castro as chancellor.

Castro resigned last month amid outcry over his handling of the allegations. He will receive an annual salary of $401,364 until February 2023 and a $7,917 monthly housing allowance for six months — all of it funded through the transition program, records and interviews show.

Records show that former Cal State Northridge President Dianne Harrison, who resigned in January 2021, was paid $277,932 for a year under an agreement approved by White.

In a public report to the trustees, her duties were described in a single sentence: “Dr. Harrison has been available to the chancellor for advice and counsel on matters pertaining to the California State University.”

Harrison told The Times that she was not required to document her work performed under the program.

“My focus was on responding to requests or a particular project, whether it took 10 minutes or 10 hours,” she said in an email response.

Harrison added that she served as a “source of historical information and organizational context” during multiple conversations with students and staff at the Northridge campus and spent time as a member of university committees. Harrison told The Times that she did not document her time because she was not required to do so.

Former San Jose State President Mary Papazian, who resigned last year after outside groups and the U.S. Justice Department were critical of her handling of sexual abuse allegations, also is participating in the transition program. She is being paid an annual salary of $290,580 until December, according to her agreement.

Records show that her duties are to prepare for a “return to a teaching position” and be available to the “chancellor and to other system executives/vice chancellors on matters pertaining to the CSU.”

When her transition payments end, Papazian will be eligible to become a faculty member on the San Jose campus in the Department of English and Comparative Literature.

Papazian said in an email response that she has advised colleagues and made herself available regarding advice to “navigate the challenges of leading their campuses during a time of significant complexity, disruption, and transformation.”

“I am using the transition year,” she said, “to reconnect with my discipline, rethink my research and writing agenda, and prepare for my engagement with a learning environment and a new generation of students very different from that from which I stepped away over 20 years ago.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.