A mask mandate was never going to save South L.A. from COVID-19. Here’s what might

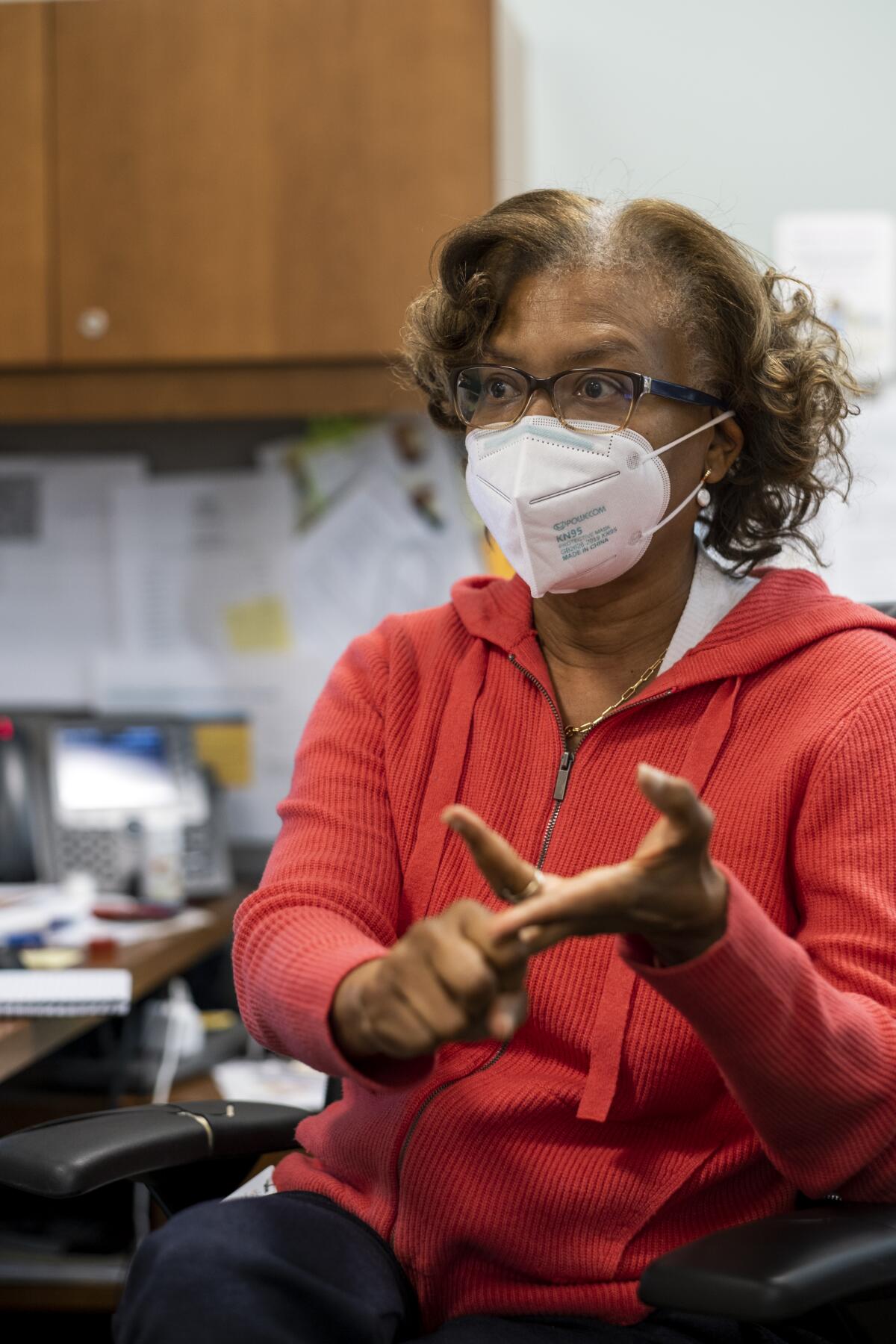

Dr. Elaine Batchlor always knew this day would come.

On Friday, Los Angeles County officially lifted its mask mandate for indoor businesses, including stores, bars, restaurants, gyms and movie theaters.

Although many people will surely continue to wear masks and many businesses will no doubt continue to require them, doing away with the blanket mandate marks a major departure from the hell of sickness and death that has been the past two years.

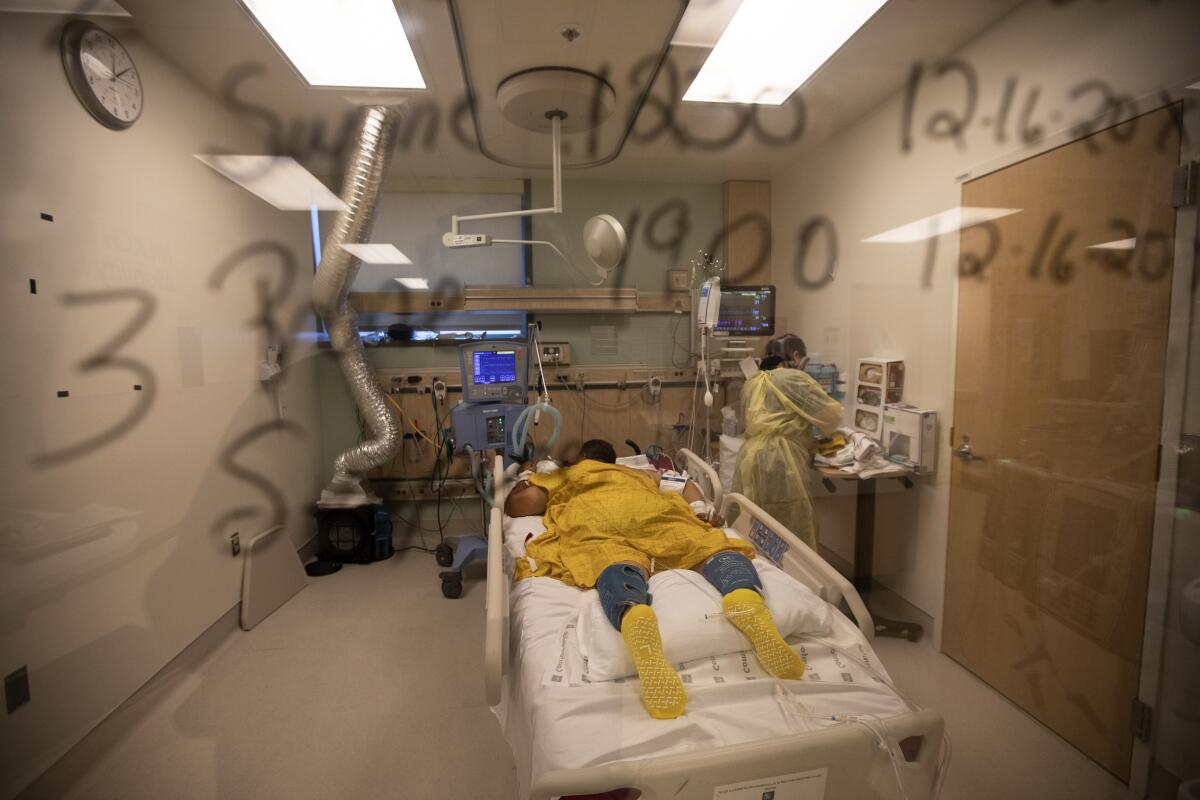

Still, Batchlor is understandably a bit uneasy about it. She is chief executive of the South L.A. hospital that, for months, was the most overrun in the county with COVID-19 patients.

“At some point,” she acknowledged, “we have to start getting more back to normal. The number of patients that are hospitalized is way, way down,” including at her Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital.

But, she added, “communities like South L.A. that have been hit hard and disproportionately affected by COVID remain at higher risk.”

Los Angeles County ended its indoor mask mandate after entering the low coronavirus community level set by the CDC.

That’s why, even as most Angelenos celebrate being able to ditch their masks, Batchlor has started pushing a deeper solution to the still dangerous disease, far beyond the use of masks and even vaccines.

As my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Luke Money reported earlier this week, Black and Latino residents of the county’s poorest neighborhoods are still getting severely sick and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionate rates.

These disparities have persisted even as coronavirus cases have plummeted in recent weeks. And, more important, they’ve persisted regardless of the population’s vaccination status.

You read that right.

According to recent data analysis by L.A. County public health officials, vaccinated and boosted Latino and Black residents ended up in the hospital for COVID-19 at more than twice the rate of vaccinated and boosted white people.

Hospitalization rates were even more stark for the unvaccinated, of course, but the disparities remained.

That’s because ultimately, beyond masks and beyond vaccines, much of the blame lies with the underlying health conditions of the people contracting COVID-19. Black and Latino Angelenos lack preventive care for the simple reason that a disproportionate number live in poor neighborhoods where doctors, nurses, pharmacies, hospitals, even urgent care clinics are impossible to find.

Neighborhoods such as Willowbrook in South L.A., where Batchlor runs Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital.

“It’s really clear that where you live and where you work has an impact on your health status. It’s no different for COVID than it is for a host of other illnesses,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said at a recent briefing. “Certainly where you live has a tremendous impact on what’s available to help you be as healthy as possible.”

So what’s the solution?

Batchlor insists she has one — at least for South L.A.

Currently making its way through the California Legislature is Assembly Bill 2426, which, if passed, would increase funding for Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital. Introduced by Assemblymember Mike A. Gipson (D-Carson), AB 2426 would make it easier for Batchlor and her staff to spend money on prevention and disease management.

“Our vision is to create an integrated healthcare system that provides affordable, accessible, high quality healthcare to people who live in South L.A.,” she told me. “You have doctors in the community, you have programs that address people who have chronic conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure and heart disease. They’re getting the medication and the education they need to manage those conditions and to prevent those conditions from getting worse.”

That sounds like what every neighborhood should have but is sorely lacking on the streets around Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital.

By Batchlor’s count, the surrounding neighborhoods — home to hundreds of thousands mostly Black and Latino residents — need an additional 1,300 doctors.

That means that when people get sick, they don’t go see a physician. Instead, they wait, and then they have to go to the emergency room as their primary source of care. All of which explains why so many diabetics in South L.A. have to get their limbs amputated — a procedure of last resort, as my colleagues Joe Mozingo and Francine Orr have reported.

State regulators impose largest-ever fines on L.A. County’s public health system — which serves the county’s poorest residents — for long delays in care.

Under Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital’s current funding formula, which is heavily dependent on Medicaid, it is losing money on emergency room visits.

“The hospital was initially designed to care for about 40,000 to 45,000 patients a year in our emergency department. And we’re seeing close to 100,000,” Batchlor explained. “We also see the results of people going without medical care in the community. So we have people coming in with chronic illnesses that have progressed to serious complications because of the lack of access to doctors.”

If AB 2426 passes, the hospital would have more money to recruit and actually pay doctors enough beyond the low payments of Medicaid to practice in South L.A.

“Ultimately,” Batchlor said, “our goal is to reduce the number of people who need to come to the emergency room.”

A South L.A. where people have widespread access to preventative care is a South L.A. where people are healthier and aren’t as vulnerable to being hospitalized or dying from COVID-19, or whatever the next plague that comes our way.

So far, Batchlor said, the response to Gipson’s bill has been mostly positive. She is “hopeful” it will pass.

Wealth, poverty and race dramatically affect the toll of the coronavirus, with Latinos and Black communities in the county continuing to be hit hard.

In many ways, mask mandates and vaccines are just short-term fixes for the longer-term disparities that have yet to be meaningfully addressed.

“The pandemic highlighted the lack of healthcare in underserved communities and the vulnerabilities of these communities,” Batchlor said. “It’s time for us to move from talking to actually solving the problems, and solving the problems is going to require changes in policy and investment.”

With the mask mandate ending and coronavirus transmission dropping, there’s definitely a risk of Los Angeles moving on from COVID-19 and leaving the residents of South L.A. to suffer. But Batchlor insists she is cautiously optimistic.

“I think that people are motivated to address these inequities,” she said. “There’s got to be a will to do that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.