California’s next attempt at universal basic income could be on college campuses

SACRAMENTO — California could send $500 a month with no strings attached to college students from low-income families as part of the Legislature’s latest approach to a guaranteed basic income plan.

State Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San Jose) is considering legislation that would create a pilot program at select California State University campuses, issuing monthly stipends for one year to students whose family income is in the bottom 20% of earners in the state. Up to 14,000 students could be eligible.

Nearly 11% of the CSU system’s 480,000-plus students said they experienced homelessness in 2018, according to a report from the Office of the Chancellor. More than 40% of CSU students reported food insecurity. For Black, first-generation college students, it was worse, with nearly 70% reporting food insecurity and 18% experiencing homelessness.

“College students are couch surfing and sleeping in their cars. This could be enough money to rent a room, and if you don’t need a room, by all means, use it for what you do need it for,” Cortese said in an interview. “It’s like a booster shot. It could help get them off of this treadmill and stop them from dropping out, being on the streets and becoming homeless long term.”

A three-campus plan would cost the state about $57 million, and a broader five-campus plan would cost about $84 million, according to Cortese’s preliminary estimates, which are based on student income data.

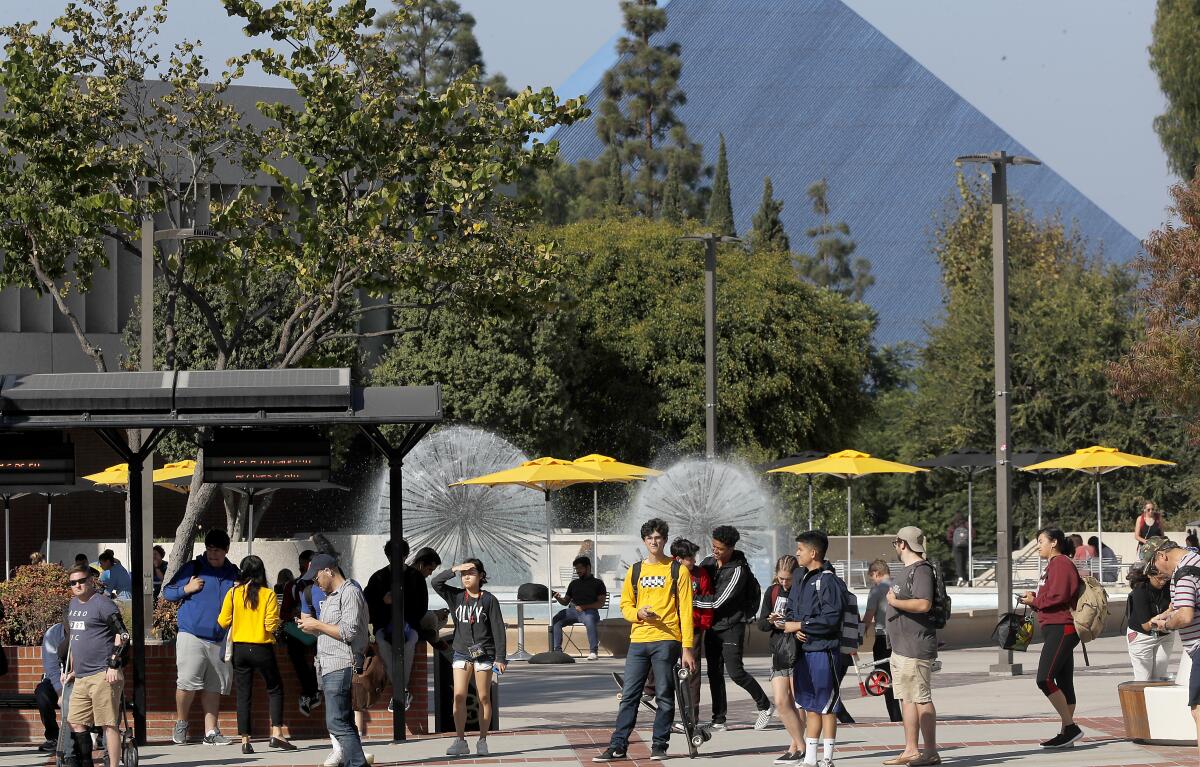

Campuses under consideration for the pilot program include CSU Los Angeles; San Francisco State; CSU East Bay; San Jose State and Fresno State.

Cortese said he will move forward with the proposal only if protections are in place so that students who receive the funding do not receive less from other financial aid programs because of an increase in income from the stipends.

The idea, he said, is to make guaranteed income stipends permanent for college students experiencing the most poverty, banking on positive results from the pilot programs.

Other universal basic income programs in the state have shown promise.

A Stockton program created in 2019 by former Mayor Michael Tubbs, now an advisor to Gov. Gavin Newsom, gave an unconditional $500 a month to income-eligible residents for two years. Preliminary findings showed the program reduced “income volatility,” enabled recipients to find full-time employment and bettered their health, according to a bill analysis by Cortese.

Last year, Los Angeles became the biggest city in the nation to launch a $1,000-a-month guaranteed basic income program.

And as part of last year’s state budget, Newsom put $35 million toward a guaranteed income pilot program for interested cities and counties, focusing on assisting foster youth who are pregnant or parents, former foster youth and other low-income Californians. Access to that program is not yet available, with applications expected to open next month, according to Newsom’s Department of Finance.

Cortese, who was also involved in developing the statewide program, said he suspects it won’t be enough to keep up with demand. Targeting the new proposal toward college students, a demographic for which the state is able to track and obtain financial information, is a smart solution to chip away at the problem, he said.

“We’ve got a captive audience, and we know where they are: in our state institutions,” Cortese said. “I would just as soon administer a program to people on the streets as well, but there’s something to be said about doing anti-displacement work amongst a population that is so reachable.”

The plan was inspired by the Silicon Valley Pain Index, a report created in 2020 by the San Jose University Human Rights Institute that focuses on wealth and racial inequalities.

Scott Myers-Lipton, lead author of the report and a professor at San Jose State, is working with Cortese on the plan and said universal basic income programs work because they cut through “bureaucratic rules” that can make it difficult for students to get the help they need.

Even critics of universal basic income, who are skeptical of the effects on the economy and joblessness, will have a hard time arguing with this college-based proposal, Myers-Lipton said.

“By having the income information of students, there could be no doubt about the fairness of it. We’ve got students sleeping in the library and living out of tents,” he said. “I would ask, ‘What’s your solution for college homelessness?’ Because what’s happening right now isn’t cutting it. We’re talking about the people that are going to be our future leaders. It’s a no-brainer.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.