Column: Moldy walls, cold stoves and broken elevators: This is life at Chinatown’s Cathay Manor

I am winded and uncomfortably sweaty by the time I reach the eighth floor of Cathay Manor, one of the last remaining affordable housing complexes for seniors in Chinatown.

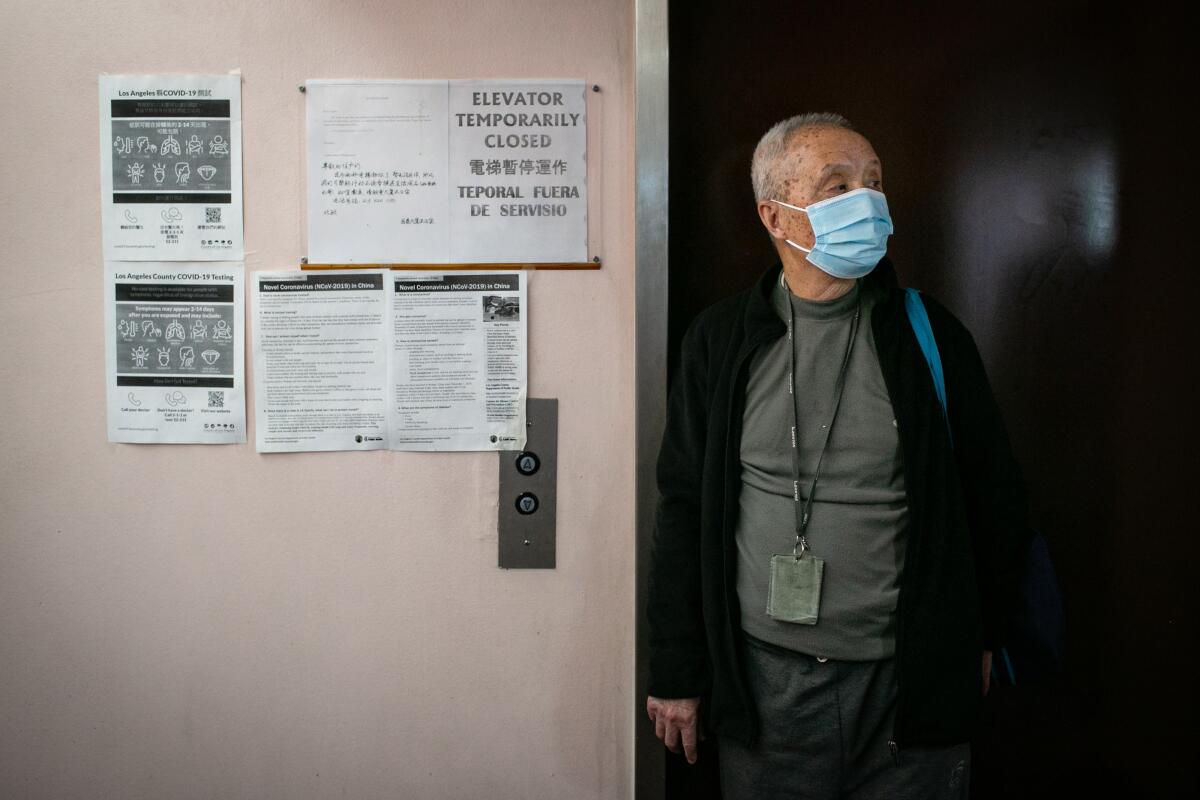

The building’s elevators have been malfunctioning for nearly a year, hence the stairs. I’m accompanying a group of volunteers from the Southeast Asian Community Alliance and the Chinatown Community for Equitable Development who have been hand-delivering one-pound bags of rice and other groceries to seniors stranded on the upper floors.

It is a tragic state of affairs for a building that was one of Chinatown’s most significant political accomplishments. Built in 1984 with a combination of private funds and federal housing grants, the bland concrete tower with Chinese architectural flourishes didn’t impress many critics.

But the building’s affordability spoke for itself. Cathay Manor had 270 units, 10,000 square feet of community meeting space, and rents stayed around $200 a month.

Broken elevators have become a common occurrence at Cathay Manor since residents moved in four decades ago, and there have always been complaints about its maintenance. But conditions have never been worse at Cathay Manor.

A building inspection in December revealed more than 300 different code enforcement violations. And the building’s landlord, Don Toy, faces 16 criminal misdemeanor charges related to his failure to fix the elevators and meet fire code regulations in a lawsuit filed by City Atty. Mike Feuer in October.

Cathay Manor was once hailed as the gateway to a new, revitalized Chinatown. Now there are toilets that flush endlessly, chirping smoke detectors and leaky faucets that have gone unfixed for so long that desperate residents use tape to stop the water.

It was a rare berth of affordability in a sea of rising rents and gentrification, with convenient access to employment centers. But residents — most are on a fixed income — now say that they’re forced to pay out of pocket for maintenance calls, which can take months to arrange: $20 for a changed light bulb, $50 to get a stove working again.

Many of the violations are small issues like broken door closers, torn window screens and carpet, and drawers off their tracks. But all over the building, there are sinks and bathtubs that don’t drain, unpowered smoke detectors and endlessly flickering lights.

Among the violations rated “high” severity are multiple instances of broken, damaged and uncovered outlets near sinks and bathtubs, a life-threatening electrocution risk.

Local, state and federal agencies are investigating Toy and the Chinese Committee on Aging, the nonprofit that developed Cathay Manor.

In September, Councilmember Gil Cedillo directed the city’s building officials to oversee the elevator repairs. In November, federal housing officials found the building in violation with federal health and safety standards. Last month, U.S. Rep. Jimmy Gomez staged a press conference at Cathay Manor and called for Toy to be fired.

Residents say the problems began when Toy fired the professional management company a few years ago and put his own employee in place. Toy defended the management change as a cost-cutting measure needed to maintain affordable rent.

In a phone interview, Toy acknowledged the building is not in good shape but claimed there were reasons for the delays. He said that CCOA is committed to fixing the problems with the building, and that they can’t fix problems that they’re not told about. He admitted it is current practice to charge for small jobs such as replacing light bulbs. He blamed the elevator repair delays on missing parts and pandemic supply chain disruptions.

“We were not trying to make money. We are trying our best to offer the best product and not raise the rent,” Toy said.

He attributed the lag in responses to repair requests to a leadership vacuum created when the building manager died last year. Toy said federal authorities have taken months to approve a new one.

But it’s surprising to hear about cost-cutting measures because Toy and CCOA receive about $3.5 million in federal funding every year.

“We don’t ask for very much — just food, water and electricity. We just want the most basic existence, and we can’t even get that,” said Muyi Yang, 82.

As Yang and her friends led me on a tour of their apartments’ woes, we walked through cracked door frames splintering from the walls. One woman lifted a curtain in her closet to reveal a large bloom of black mold. In one apartment, there were food-storage containers under the sink to catch leaking water. In another, the faucet was dry and inoperable.

At one apartment, the doorknob was covered with tape to hold the door open or else it would swing shut and lock the resident out permanently. Other doors were held closed with tape because they would not lock or close at all.

“There’s just a lack of humanity and caring,” said Momo Hu, 87.

Mr. Chu, who declined to give his first name for fear of retaliation, has tried to complain about the building’s problems before. In 2014, Chu contacted the World Journal, a Chinese-language newspaper, which ran a story about the broken elevators.

Instead of fixing the problems, management tore down the copies of the newspaper he pasted around the building, Chu said. He was called into the manager’s office and yelled at for contacting the newspaper.

“This is America,” Chu said. “This is Los Angeles. Things are not supposed to be like this. It’s just too much hardship.”

Cathay Manor deserves better. Despite the building’s longstanding issues, it remains one of the only places that seniors in Chinatown can afford to stay. The waiting list is thousands of people long.

When the slightest rumor of open units spreads through the community, the line of hopeful tenants at the leasing office stretches down the block.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.