The sense of emptiness gutted him. Sketching in his notebook in the dim light of his room didn’t bring Sergio Nuño the usual solace. He could barely summon the will to pour a bowl of cereal.

Nuño, 23, was on summer break from community college and laid low by depression and anxiety. He rarely left his parents’ apartment in Compton.

Late one night in August 2019, intrusive thoughts were telling him to bang his head on the wall. Trying to stop the suicidal impulses, he clenched his jaw and paced circles in the living room until his mother and father woke up.

The only therapists and psychiatrists his parents, immigrants from Jalisco, Mexico, ever saw were on TV. Back home, going to one branded you as crazy.

In South Los Angeles and surrounding areas like Compton, mental disorders mostly go untreated until they have caused irreparable damage.

Richard Perry, who by his own sheer grit built a middle-class life for his family in Compton, was waging battle on two fronts: Fighting against COVID-19, and trying desperately to hold on to everything he had worked for.

Many of them are inextricably tied to other calamities that befall people who live in L.A.’s poorest neighborhoods at disproportionate rates. Even before COVID-19 hit, Latino and Black people here were dealing with more poverty, addiction, unemployment, chronic disease, homelessness, disability and childhood trauma, all of which worsen mental conditions, which then further feed those underlying problems.

Behavioral health practitioners fear the pandemic has accelerated this spiral in a way they will be coping with for years and decades to come.

Under the Affordable Care Act, Medi-Cal began covering care for mild to moderate mental health conditions in 2013, but access to care has remained low in low-income areas of color. The city of Compton has just five licensed psychologists. Santa Monica, slightly smaller in population, has 361. The system is skewed heavily toward those in wealthier communities who can pay out of pocket.

“What I see in South L.A. is unfathomable,” said Dr. P.K. Fonsworth, a bilingual addiction psychiatrist who works at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in Willowbrook. “There’s two different Americas in mental health.”

Four days a week, the psychiatrist works in the emergency room at MLK and sees the relentless ravages of long-untreated mental illness.

“It’s a deep hole and you just fall into it. We call it a system but it isn’t a system.”

— Sonya Young Aadam, chief executive officer of the advocacy group California Black Women’s Health Project

With his parents’ help, Nuño found his way to MLK’s outpatient clinic on Rosecrans Avenue. He was lucky his father had a family insurance plan through his job at the Cheesecake Factory in Cerritos. Fonsworth prescribed him medication and scheduled him for biweekly follow-ups.

Within weeks, the improvement in Nuño’s mental health was palpable. He had a job at Home Depot, began selling his artwork, and was accepted to the Otis College of Art and Design for next fall. He wants to become a toy designer.

“When we invest in people and care for people, they can get better and have more meaningful and connected lives,” said Fonsworth.

But he likens to much of what he does to treating “end-stage organ damage” because the preventative care did not occur.

Mental health in South L.A. has been so neglected it is still largely uncharted terrain.

“The number of people in need is massive,” said Dr. Jonathan Sherin, director of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. “The exact number is difficult if not impossible to track because the system is so fragmented.”

A Los Angeles couple has worked hard to eke out a living and provide for their daughter, who is trans. When COVID hit, they feared who would protect her after they’ve gone.

L.A. County operates centers to treat people with more serious mental illness, but they are vastly inadequate. There is no clean hand-off from hospital emergency rooms for acute patients, or to the managed care plans for those who are improving — leaving bureaucratic fissures on both sides.

“It’s a deep hole and you just fall into it,” said Sonya Young Aadam, chief executive of the advocacy group California Black Women’s Health Project. “We call it a system, but it isn’t a system.”

The Department of Mental Health is working to bring a “full continuum of services” to South Los Angeles, Sherin said, in part with the opening next year of the $335-million Mark Ridley-Thomas Behavioral Health Center, with 32 beds for acute patients.

But one of the biggest obstacles to care in South L.A. is the overall lack of outreach to Black and Latino communities to remove the stigma from mental health care.

When you talk to someone who doesn’t understand it, it’s like talking to a wall.

— Courtney, who summoned the courage to seek treatment 11 years ago

Courtney, 35, first summoned the courage to seek treatment with the county 11 years ago. When she got off the bus on East 120th Street and saw the sign for the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Building, she flushed and walked in the other direction, terrified someone she knew might see her.

When she saw no one paying attention, she switched course and slipped inside.

Courtney, who is Black and asked to use only her first name, was raised at first by her father’s mom in Perris in Riverside County. Her grandmother was nurturing, and they slept in the same bed, talking as they fell asleep. When her “Nana” sensed Courtney was awake in the morning, she’d tickle-scare her: “Raaa!”

But Courtney’s life was upended at age 8 when her mother came to take her to L.A. “I can’t live with Nana anymore?” she cried.

She does not remember if she was sad before that day, but she has felt lonely ever since.

She was bullied and isolated in school and at home by her seven siblings. Dark thoughts crept into her mind. She questioned her own existence. “I felt like wasted space,” she said.

Even if she turned to her closest aunt, her dad’s sister, she was rebuffed. “You should just shake it off.” She didn’t even bother telling her mother.

No medical procedure more visibly demonstrates how COVID-19 became especially deadly in these neighborhoods than diabetic amputation.

“When you talk to someone who doesn’t understand it,” she says, “it’s like talking to a wall.”

As she grew older, she saw movies with white people seeing therapists, and ads for antidepressants asking: Do “you feel sad or lonely?” Slowly she developed a nascent awareness of the concept of mental health care.

And so she found herself at Augustus Hawkins that day, speaking to the therapist, releasing a lifetime of bottled-up emotion. She felt like she could breathe for the first time.

While her anxiety and depression did not vanish with therapy and medication, they became more manageable. She began to socialize more.

But the stigma was pervasive and painful. Her friends and several boyfriends made comments about her medication.

“The meds are fake,” one said. “It’s a way for the industry to control you.”

“Depression’s not a real thing, everyone feels bad sometimes.”

“That’s for white people.”

And when she started feeling better, she wondered if she truly needed the drugs. She fell into a cycle of dropping out of treatment, then deteriorating, then going back to Hawkins.

When she wasn’t working as a security guard, she stayed in her apartment in the Nickerson Gardens Public Housing Project in Watts, cartoons playing on the TV on mute. Eventually she stopped going to Hawkins altogether.

For many patients, intubation can be a last effort to stave off death. But that doesn’t mitigate how terrifying the experience can be.

In 2019, Courtney landed in the emergency department of MLK Community Hospital in severe pain from endometriosis. As part of a new initiative to integrate behavioral and medical care, a mental health counselor screened her and referred her to Fonsworth.

Since the privately managed hospital opened in 2015 as a linchpin of healthcare in South L.A., practitioners there have been struck by the degree of mental illness and addiction in patients who came to the hospital for complications of diabetes, cancer, heart disease, emphysema.

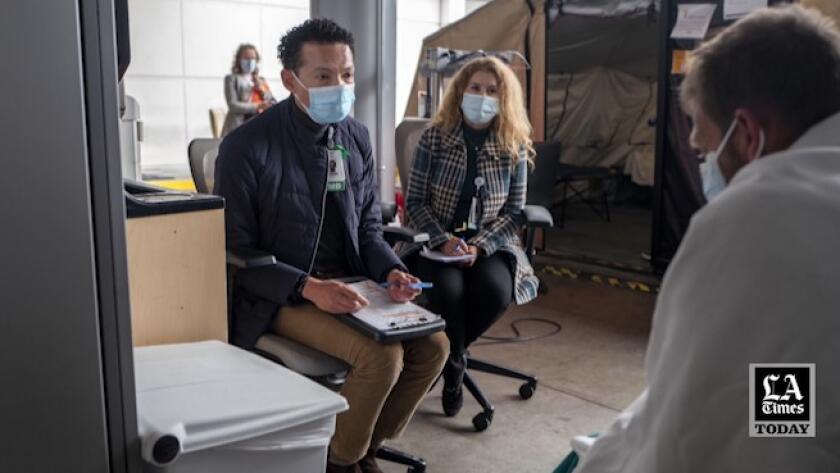

The hospital set up a team of social workers and counselors to get those patients into long-term treatment within its own health network and outside it. Just in the first two months of 2021, Fonsworth and a mental health counselor identified 113 people in the emergency department or other wings of the hospital in need of some kind of residential or outpatient therapy. Only 29 declined the referral.

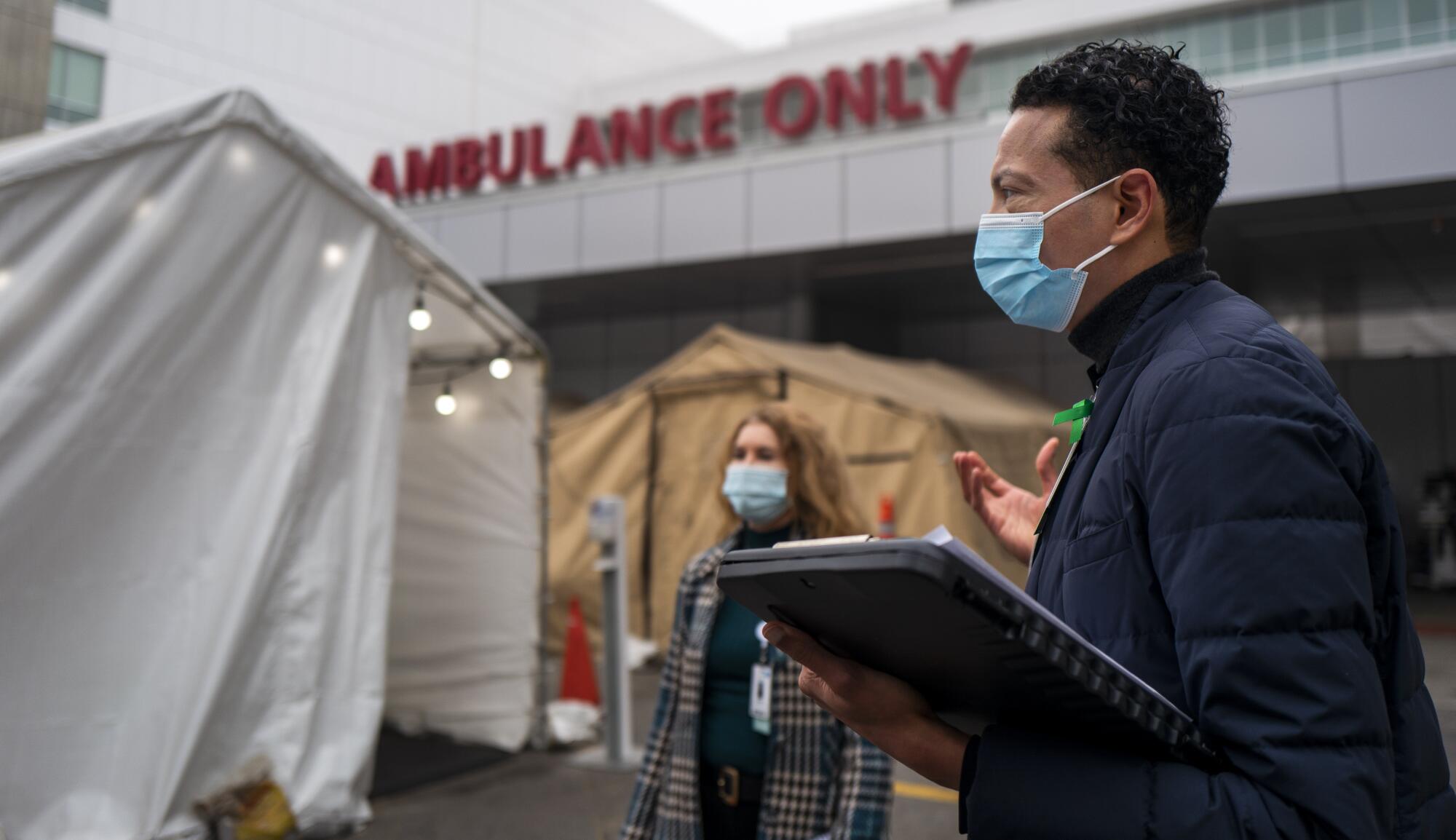

On Dec. 2, while assessing patients in the hospital for psychiatric problems, Fonsworth examined a 42-year old homeless white man, David Varvarosky, a day after he came to the emergency room in a state of psychosis with sores all over his hands. He had tested positive for methamphetamine and marijuana.

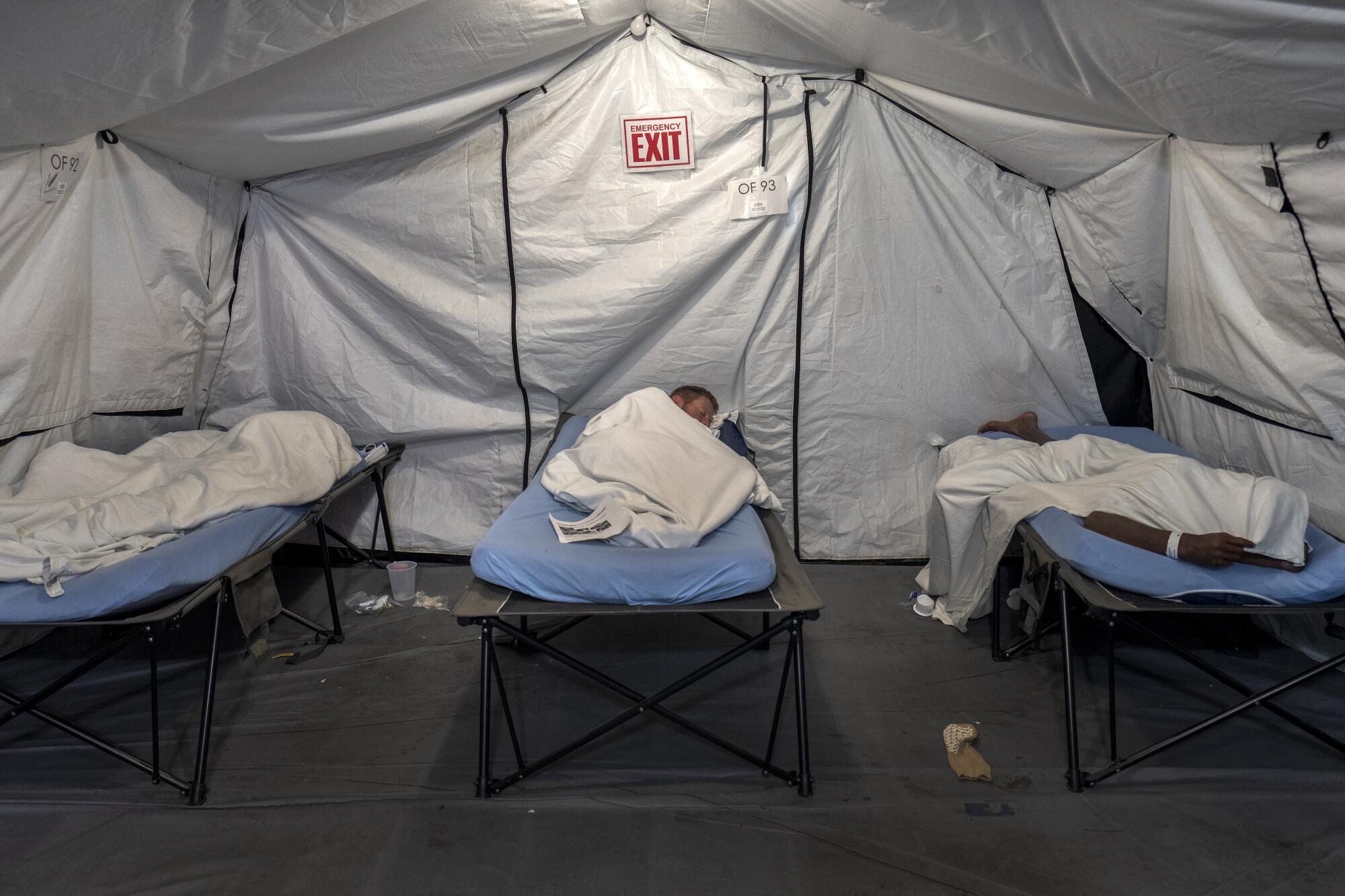

Varvarosky rested in a heated tent by the entrance of the overcrowded ER. He came out and sat in a chair, swiveling his head around, twitching slightly. Fonsworth delicately questioned him about his life.

“David, help me understand, do you have any trouble with drugs or alcohol?”

“I do drugs and alcohol, but I don’t have trouble with them.”

“Have you ever been to rehab?”

“No.”

“David, is rehab anything you’re interested in?”

“No, I don’t have a drug problem.” He mumbled about God creating drugs for a reason. “Jesus drank wine.”

“David, have any psych meds been helpful for you?”

“Yes, Buspar and Wellbutrin,” Varvarosky said. He had been in treatment at some point.

Fonsworth tried to get more at his troubles.

“David, anyone in your family die from suicide?”

“Yeah.”

“Who was that?

“My dad.”

“What was going on with your dad, what happened?”

Varvarosky closed his eyes and turned away, clearly not wanting to talk about it. “I don’t know, he just shot himself.”

He was done. He just wanted to get his sores treated and get back on the street, and the next day he walked out of the emergency room with the only relief Fonsworth could give him — a month’s supply of medications.

Far more rewarding to Fonsworth are the patients who are open to the benefits of long-term treatment.

Adrith Felix, 25, sank into paralyzing depression as a child when her father left the family to live with another woman in Chicago. She would sit in the one bathroom of her tiny apartment and silently cry. Her mother, Blanca, an immigrant from Nayarit, Mexico, couldn’t understand her moods. On the surface, Blanca had had a much more difficult childhood than her daughter.

“Oh, you should be thankful that you have me here,” Blanca would say. “I didn’t have my parents because I came over here and I had to do things on my own.”

Felix learned to keep her emotions silent, until she was 13, and took about a dozen Naproxen pills and was taken to the emergency room, then to a psychiatric hospital in Costa Mesa.

Her father flew from Chicago and lectured her. “You’re smarter than this,” he said.

Nurses removed her shoelaces and the wire in her bra to prevent another suicide attempt. Felix felt ashamed, and scared to be alone in a hospital filled with patients she saw as crazy.

But group counseling taught her she was not alone, and she left three weeks later with insight into her condition and a referral to therapy at Augustus Hawkins.

With the help of social workers, her mother gradually understood her daughter’s need for treatment.

After high school, Felix enrolled at Cal State Northridge and majored in psychology, hoping to return and help her community in South L.A. She had gone to white therapists whom she simply couldn’t connect with because they didn’t understand her background. She knew there needed to be not just more Latino and Black practitioners, but doctors and counselors with training in the cultures of the communities they worked in.

She was busy at Northridge as a student advisor for Latinas on campus and a listener at a crisis intervention line, buoyed by the social network of her fellow students.

But when Felix graduated and came home, she lost that network and her thread of purpose. She got a job helping autistic students navigate the classroom, and otherwise stayed in her apartment, watching Netflix. She had gained 40 pounds, and didn’t feel like she was worthy of grad school.

She called her mom’s insurance plan and was referred to a therapist, Linda Espinoza, at the MLK clinic on Wilmington Avenue. She hit it off with Espinoza, who urged her to reconnect with old friends, get exercise and keep a self-esteem journal. Fonsworth helped explain how a better diet could improve her mental state.

She rebuilt her confidence and now runs three miles a day, and this winter break is sending her applications for master’s programs in social work.

Nuño has turned 25, and will be off his dad’s insurance on Jan. 1. He is worried that, even if he gets Medi-Cal, he won’t be able to see Fonsworth or will have a gap in his medication.

Courtney’s managed care through Medi-Cal stopped approving visits to Fonsworth, and she dropped out of treatment, not up to the struggle of finding another provider who understands her. Her anxiety is growing worse and she now fears taking medication. She’s gone to the dentist six times and each time left in a panic before she got in the chair.

But she is managing, as she always has. She wonders what her life would have been like if her mom took her to treatment in her formative years. Would she have gone to college? Would she have a profession?

“I just can’t imagine what I could have done with that help.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.