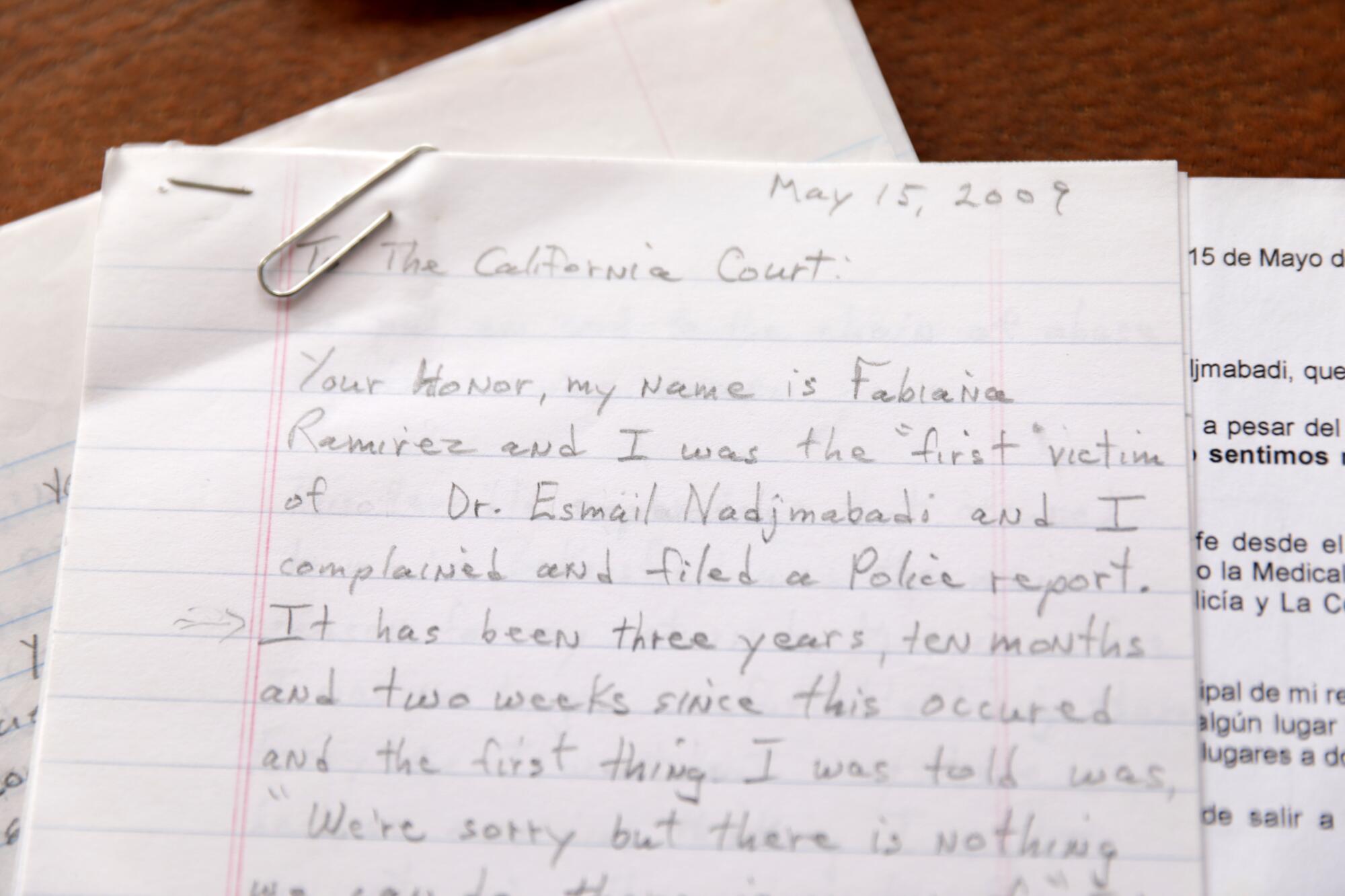

Fabiana Ramirez Flores, 51, on Sept. 29 at her home in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico. Ramirez was one of the first women to come forward after being sexually abused by Dr. Esmail Nadjmabadi in 2005.

Fabiana Ramirez Flores went to Dr. Esmail Nadjmabadi, a family friend, for a spider bite behind her knee. Alone in his exam room, he sexually abused her on the pretext of screening her for colon cancer.

“I was in shock,” said Ramirez, whose ordeal didn’t end there.

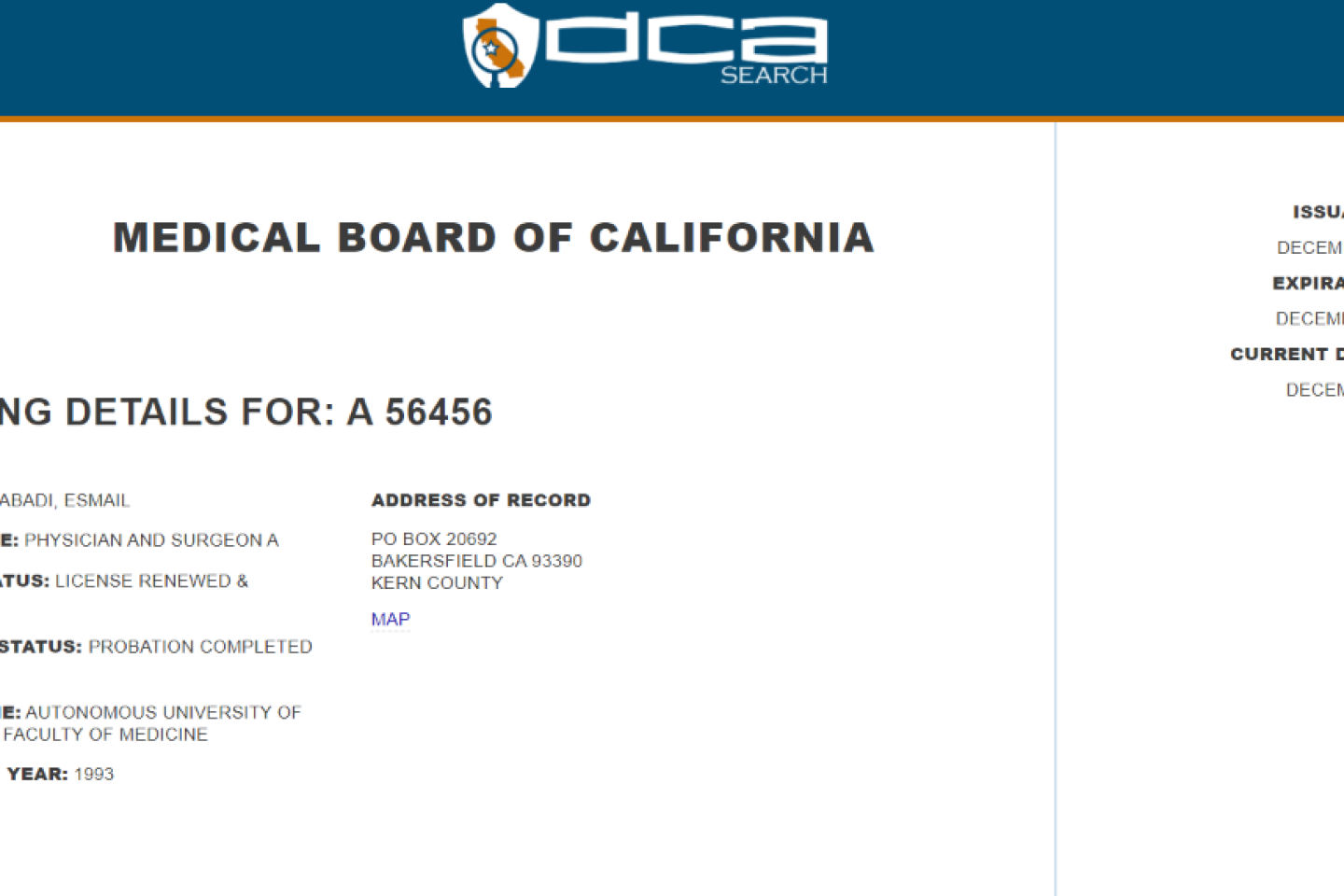

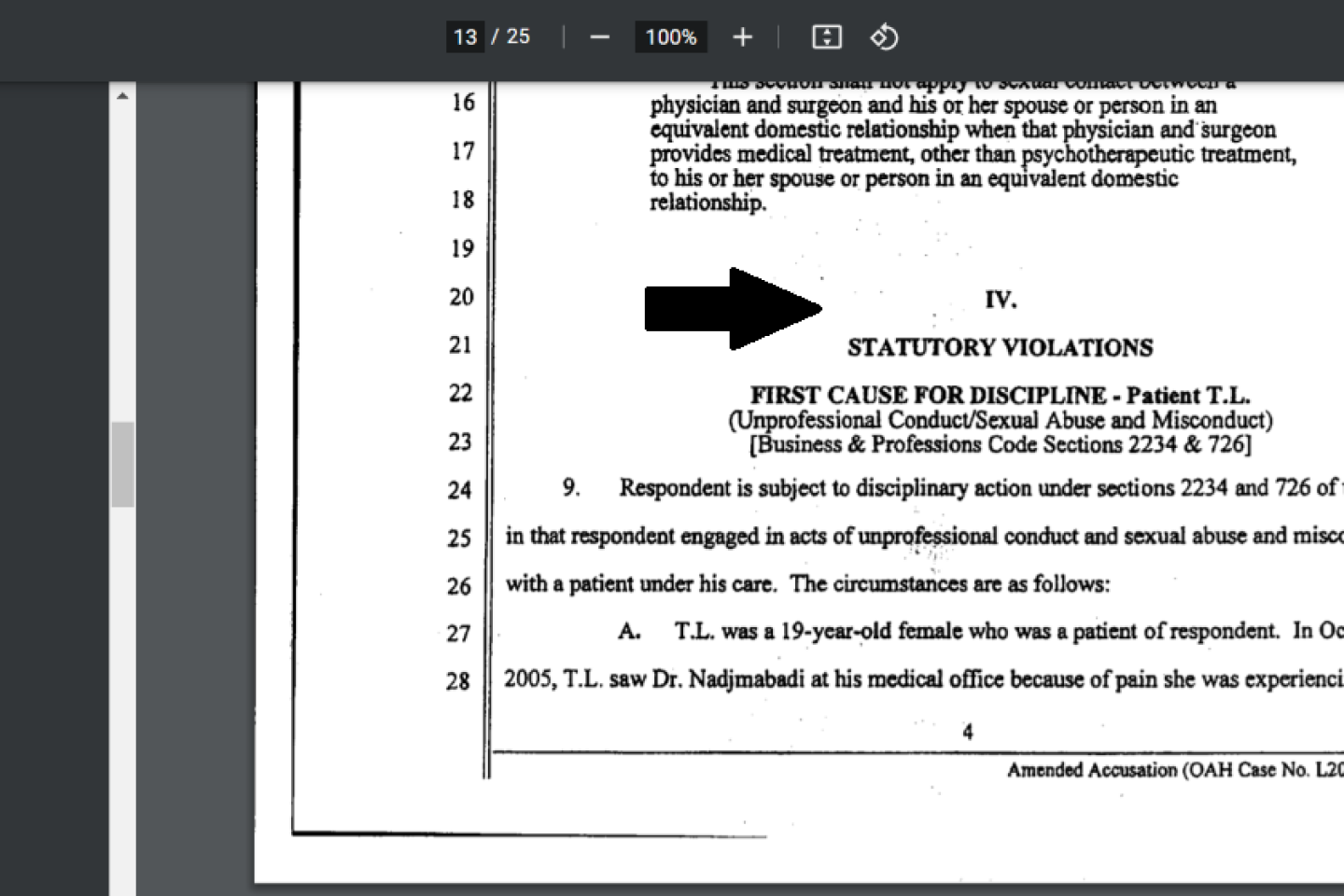

Nadjmabadi, a Bakersfield internist, persuaded a female staff member to lie to police about being in the room, according to an accusation filed by the Medical Board of California. Then he reported Ramirez and her husband — both undocumented immigrants from Mexico — to immigration officials in a bid to make them “unavailable” to investigators, Medical Board records said.

Five other female patients — including one in her mid-teens — told police and state regulators about similar sexual misconduct by Nadjmabadi. In 2009, he pleaded no contest to a criminal charge of sexual exploitation by a physician involving two or more women and the following year surrendered his medical license.

It appeared his career was over until five years later, when he petitioned the Medical Board for reinstatement. The board granted his wish. It was a surprise to Ramirez and the other women he abused.

“I don’t know how they can return a license to someone like that,” Ramirez said after learning of his reinstatement from a Times reporter. “He was taking advantage of vulnerable women.”

A Times investigation found that Nadjmabadi was one of 10 California doctors since 2013 who successfully regained their licenses after losing them for sexual misconduct.

The state Medical Board reinstated more than half of all sex abusers who sought to get their licenses back, a rate significantly higher than for doctors who lost their licenses for all other reasons, a Times review of board data found.

Any sexual contact with patients violates a physician’s code of ethics as laid out by the American Medical Assn. and violates California law.

But the board has wide latitude when considering applications for reinstatement, even in cases of severe misconduct such as physically assaulting patients, sexually abusing minors or lying to police.

The list of those reinstated physicians includes Dr. Zachary Cosgrove, 57, a Bakersfield family practitioner who slept with three female patients, then turned violent when they reported him to authorities, according to the Medical Board accusation. He kicked and punched one, threw furniture at another and told the third, “You’d better just kill yourself. ... That’s going to hurt less than what I’m going to do to you,” the accusation states. Cosgrove admitted to the allegations as part of his petition to be reinstated.

Also on the list is family practitioner Dr. Hari M. Reddy, 68, of Victorville in San Bernardino County, who inappropriately touched two teenage patients during exams and harassed one at home after hours, according to Medical Board records. He called, asked her to a restaurant and said, “Oh, I bet you’re naked. I bet you’re sitting there on your couch naked.” Then he made kissing sounds into the phone, according to board records, which state that when she threatened to report him to police, he said, “It’s your word against my word.”

Both doctors are currently practicing.

The California Medical Board has long battled allegations that it goes easy on bad doctors and fails to protect patients. The majority of the board’s members are doctors. A Times review of Medical Board records found that the panel relies heavily on a doctor’s evidence of rehabilitation, usually with the testimony of therapists hired by the doctor, and no input from the patients who were harmed.

Board President Kristina Lawson refused to discuss the details of individual cases or explain why the board granted specific reinstatements, citing privacy laws. Lawson defended the panel in a recent interview, saying, “My colleagues on the Medical Board, 100% of them, are dedicated and committed to protecting California consumers. It’s the number one, top-of-mind consideration for all of them in all of the work that they do.”

Lawson conceded that the board has “room for improvement.” She said it is bound by state regulations that, among other things, prevent it from deeming some offenses — such as sexual misconduct with a minor — permanently disqualifying.

“I can’t go rogue,” she said. “We have to operate within the confines of the law.”

But once a physician’s license has been revoked — a rare and extraordinary step in California — there is nothing that requires Lawson and her colleagues to reinstate it. That is up to the board’s judgment.

The Medical Board of California was established to protect patients by licensing doctors and investigating complaints. The board has a long history of going easy on troubled doctors, a Times investigation has found.

In the wake of questions raised in this report, Lawson said she has directed the staff to look into notifying victims before reinstating doctors’ licenses and providing a venue for victims to be heard during the reinstatement process.

::

Former Fountain Valley physician Dr. Shahab “Sean” Ataee was convicted of sexual abuse in 2001 in New York for groping the daughter of a patient in an intensive care unit. While ostensibly showing the daughter how to stretch her comatose mother’s legs, Ataee fondled the young woman’s breasts and attempted to shove his hands down her pants, according to California Medical Board records.

After his conviction, Ataee tried his luck out West. He applied three times for a California medical license. Each time, the California Medical Board rejected him, citing his record of sexual abuse. The third time, an administrative law judge examining the evidence noted that Ataee “continued to adamantly deny having committed any sexual offense” and “had not made a sufficient showing of rehabilitation,” according to board records.

Ataee took a different tack the fourth time. He enrolled in an intensive sex offender treatment program and participated in follow-up therapy “intended to prevent future problems,” according to board records.

Part of his plan was to have a chaperone in the room whenever he treated women.

“This administrative law judge was very impressed with [Ataee’s] showing of rehabilitation,” wrote Greer D. Knopf, who reviewed the new application and recommended that the board grant him a license, which it did in February 2009.

Even when it accuses a doctor of paralyzing or killing patients, the Medical Board of California often lets the doctor keep practicing.

The rehabilitation didn’t last long.

In April 2012, a woman who’d hurt her back in a car accident went to the Mission Viejo clinic where Ataee was working.

There was no chaperone in the exam room when he told her to undress, according to the lawsuit claiming sexual battery she filed soon afterward. While she lay on the exam table, he put his hand between her legs and “moved his fingers around” her pubic area, she alleged. She didn’t realize he wasn’t wearing gloves “until she saw him sniff his fingers,” according to the lawsuit.

Ataee didn’t admit to the allegations, according to Medical Board records, but the owner of the clinic, who said Ataee never told him about the conviction in New York, paid $1 million to settle the lawsuit. The Medical Board, which is required to be notified of any malpractice settlement greater than $30,000, took no action. Asked whether they knew about the settlement, Lawson and board spokesman Carlos Villatoro said they are prohibited by law from discussing specific cases.

“It amazed me he had a license,” said William Seegmiller, the patient’s attorney at the time. It seemed to him that lenience was baked into the culture of the Medical Board: “It makes a fertile ground for these folks. They get some psychological counseling [and] say, ‘I’m fixed.’”

In 2016, another woman, a registered nurse, sought relief from neck and shoulder pain at a Fountain Valley clinic where Ataee worked. The two were alone in the exam room, according to Medical Board records.

During the treatment, as Ataee bent over her, he fondled her breasts repeatedly after she told him to stop, she said. She could also feel his groin pressing against her arm. She pulled her arms closer to her body and “tried to make herself smaller,” according to the records.

Resources are available, but checking your doctor’s track record can be difficult. Here are some tips.

Then he told her to stand up and walk in circles. He followed, putting his hands on her hips and working his right hand down the front of her underwear until his fingers rested on her genitals. She then felt him “press his hardened groin against her butt,” according to board records. When he told her to bend over, she refused, ending the session.

The receptionist for the clinic later told investigators there had been two similar complaints about Ataee, according to board records.

Ataee denied the allegations, but the Medical Board revoked his license in 2019. Ataee did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this report.

Ataee has not sought reinstatement; doctors must wait three years before applying.

But 10 of the 17 physicians who lost their licenses for sexual misconduct and petitioned for reinstatement since 2013 succeeded, board data show — a rate of 59%. By contrast, The Times found, 47 of the 105 doctors who lost their licenses for all other reasons — fraud, substance abuse, gross negligence — got theirs back, a rate of 45%.

Serious malpractice leading to the loss of limbs, paralysis and the deaths of patients wasn’t enough for the California Medical Board to stop these bad doctors from continuing to practice medicine.

Lawson said she was “unable to verify” The Times’ numbers. She declined to say whether she would ever seek treatment from any of the doctors who committed sexual misconduct, contending that it was not a fair question. She encouraged patients to do their own research on the Medical Board’s website.

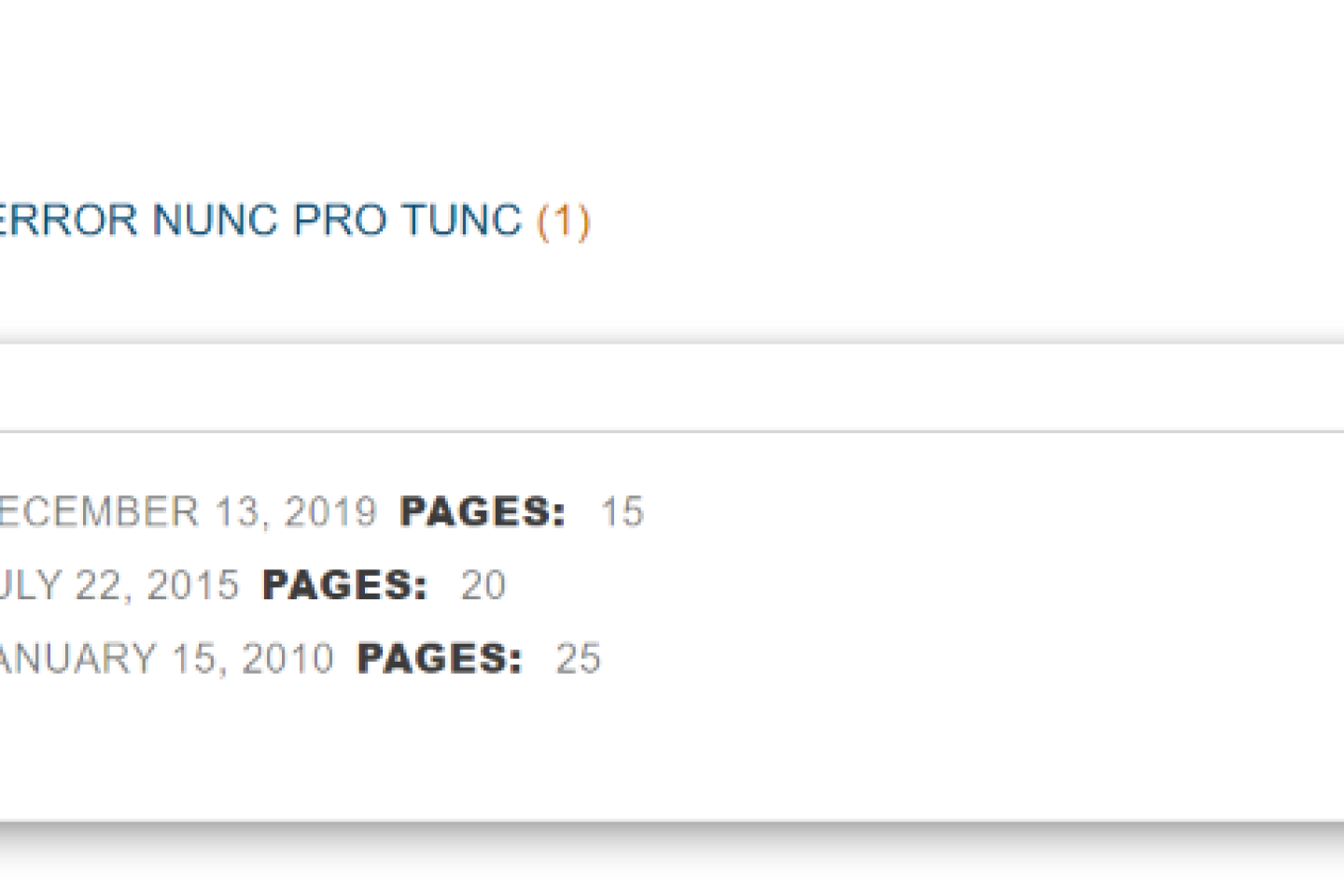

But the first two pages of the profiles for Nadjmabadi and Reddy offer no details about their misconduct beyond a cryptic and easily overlooked notation of “Probation completed.” To find details of what they did, a patient must scroll far down the second page, know that the important information is buried behind a link labeled “Decision,” then plow through the legalese in dozens of pages of PDFs.

Doctors seeking reinstatement appear before administrative law judges and must present “clear and convincing” evidence of their rehabilitation. Some seek to bolster their cases with the results of mental health therapy sessions or psychiatric evaluations.

The administrative law judges recommend whether to reinstate, but the final decision rests with the Medical Board.

The process is inherently flawed, said some experts, because the board allows mental health providers to be selected and paid for by the doctors.

Many choose to see family and marriage counselors or sex-addiction specialists, when what they really need are certified sex-offender therapists who will provide more rigorous and appropriate treatment, said Rory Reid, a UCLA research psychologist and assistant professor of psychiatry who has treated compulsive sexual behavior disorder and sex offenders.

Doctors accused of sexual misconduct should be required to pick from a provider list approved by the Medical Board to ensure they receive appropriate therapy, Reid said. But the board maintains no such list.

All the doctors who committed sexual misconduct and got their licenses back provided testimony from therapists who said they were safe to resume practicing, The Times found. They also acknowledged that their accusers had been telling the truth. Most also mentioned receiving spiritual guidance.

Cosgrove, the Bakersfield family practitioner, hit all three points during his successful bid for reinstatement in 2016.

In January 2003, Cosgrove began a sexual relationship with a 27-year-old patient. He stayed at her apartment two or three nights a week until June, when he pushed her against a wall and threw a shoe rack at her, according to board records. Bruised and shaken, she gathered her kids and fled before contacting police. She got a restraining order against Cosgrove, which he soon violated. He pleaded no contest and served a year’s probation for the violation, according to board records.

Another patient told investigators she initially consented to sex with Cosgrove in July 2004. But then he held her by the neck and rammed “his penis back and forth inside my mouth” so forcefully her eyes watered and she struggled to breathe and nearly blacked out, she said. Later, when she threatened to report him to authorities, he showed up at her apartment, where he became enraged, according to board records. He punched her, kicked her and told her, “I’m not going to lose my career.”

In 2006, Cosgrove turned up drunk and shoeless at the door of a third patient he’d been dating for a few weeks. She asked The Times to identify her only by her initials, T.T. Cosgrove helped himself to a few of her prescription Xanax tablets, and they had sex. A few days later, T.T. reported Cosgrove to the human resources department at the clinic where he worked.

Soon after, Cosgrove appeared at T.T.’s door again. He barged in uninvited and demanded that she call the clinic back and say her complaint against him was untrue. T.T. said she refused. Then Cosgrove told T.T. — who he knew was being treated for depression and an anxiety disorder — to kill herself because it would hurt less than what he was going to do to her.

“He knew that I was vulnerable,” T.T. told a Times reporter in a recent interview. “He knew that I was depressed, and I was taking antidepressants, and he said for me to kill myself,” she recalled before starting to cry. “Who does that?”

Cosgrove was arrested for making a felony terrorist threat, felony assault with intent to cause great bodily injury and felony witness intimidation, according to board records. He pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of dissuading a witness.

Times reporters’ dedication to accountability reporting inspired countless stories ranging from breaking news to features to hard-hitting investigations. Here are some of those stories.

Cosgrove surrendered his license in 2008. Despite counseling and letters of reference from two church pastors, his first attempt to get reinstated in 2011 failed.

At the hearing for his second attempt in 2015, Cosgrove offered a new reason for his prior behavior: addiction to methamphetamine, which he said led to “hypersexuality.”

He had smoked the powerful drug twice a day the entire time he had practiced in California — eight years.

But he had been sober since December 2006, Cosgrove told board members. “I went off the rails. I admit that, and my behavior was abhorrent, but I’m back,” he said. “I’d like the chance to redeem myself and help people.”

Supervising Deputy Atty. Gen. Robert Bell, representing the state at the hearing, was skeptical of the psychiatrist Cosgrove visited between his first and second hearings, describing him as the kind of doctor a lawyer sends a client to because they are “in the business of getting people their licenses back.”

An insider’s complaint asks the state to investigate the board, which he says fails to properly discipline doctor misconduct and dismisses patients’ claims.

The psychiatrist, located in Texas, did not appear at the hearing. His testimony, that it was safe for Cosgrove to practice if he stayed away from drugs and alcohol, had been submitted in writing.

Howard W. Cohen, the administrative law judge who heard the case, advised against giving Cosgrove’s license back. The board, however, found that Cosgrove was sufficiently “remorseful” and “committed to not failing again” and reinstated his license in February 2016.

T.T., now 45, said she never heard from the Medical Board about Cosgrove’s reinstatement.

“It’s kind of like a slap in my face,” she said. “Whoever authorized him to get his license back — would they be fine having their daughter, wife or sister see him? Why don’t they put themselves in our shoes?”

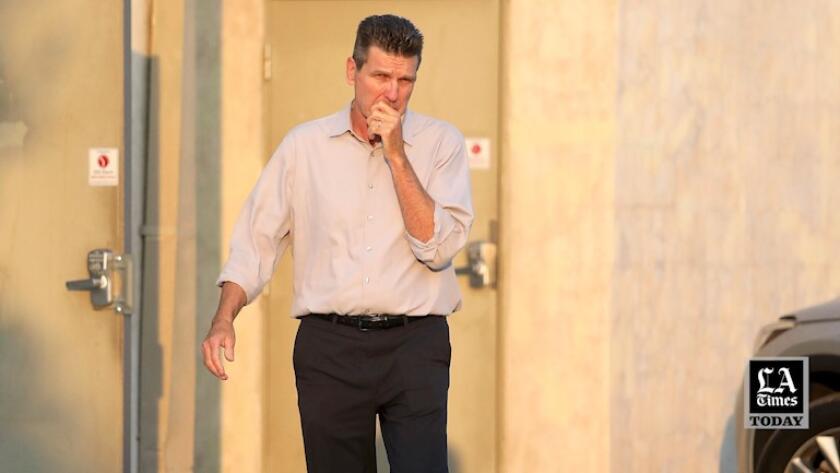

In a brief interview outside the Industrial Medical Group in Bakersfield, where he now works, Cosgrove said he “absolutely” deserved to get his license back. “I went through a lot of rehabilitation,” he told a reporter. “I think second chances are a good thing.”

Cosgrove, who told The Times he “went through a lot of pain and suffering” after the women reported him, said there was no need for the Medical Board to inform his victims about his reinstatement.

“Those hearings weren’t about them,” Cosgrove said. He had already admitted his guilt, “so why do they need to be heard from?”

Reddy, the doctor in San Bernardino County, found a counselor who was willing to cast at least partial blame on the victims.

In January 1998, an 18-year-old woman came to the emergency room at an Upland hospital complaining of severe itching all over her body.

Reddy examined her genitals with an ungloved hand, according to an accusation filed by the Medical Board, which said he also touched one of her breasts.

He later made a series of phone calls to the young woman at her home and workplace. The doctor, then in his mid-40s, pressed her with questions about school and her boyfriend, according to the Medical Board.

The young woman threatened to report Reddy to his employer or the police, but he told her no one would believe her, Medical Board records state.

The next year, in August 1999, Reddy examined a 15-year-old girl who suspected that medicine he prescribed for her stomach problems was irritating her genitals. Reddy instructed her to lie on the exam table, lift her shirt and bra and raise her hands over her head, according to a Medical Board accusation.

While examining her breasts he told her she had “beautiful lips.” He later kissed her head and quizzed her with explicit questions about her sexual habits, the accusation said.

Finally, Reddy grabbed the teenager, pulled her toward him and tried to kiss her on the lips, the accusation states. When she pushed him away and said, “No!” he walked out.

The girl reported the encounter to the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department in Victorville, which then recorded a call between her and the doctor. When she asked why he tried to kiss her, he apologized, according to Medical Board records, and when told that he had made her uncomfortable, he promised not to do it again.

Reddy was charged with three counts of lewd acts on a child. In April 2002, he pleaded no contest to a reduced charge of battery, and a judge placed him on probation for 36 months.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

That July, the board sought to revoke his license, accusing him of sexual misconduct with five female patients, including the 18-year-old and the 15-year-old. Reddy denied the allegations.

To satisfy terms of his criminal probation, Reddy received counseling from a licensed clinical social worker, who also was a licensed marriage, family and child counselor. The therapist concluded that there was “a cultural factor” at play in the allegations against Reddy and that his “friendly, easygoing approach” might have been misread by some female patients.

“They can interpret friendliness as an invitation into sex or romance,” the therapist said, according to board records. “I have helped Dr. Reddy spot that kind of situation and helped him develop techniques to keep such patients at proper distance. In a way, it is sad that professionals have to conduct themselves this way; however, it is a reality of modern life.”

Roy Hewitt, the administrative law judge, rejected the therapist’s findings, concluding that Reddy had exhibited “predatory conduct over a period of time” and had lied about it.

“He was literally and figuratively ‘feeling his patients out’ to see if they were interested in pursuing relationships with him; and, he did so under the guise of conducting medical examinations,” Hewitt said in his decision.

The board revoked Reddy’s license in 2003.

In 2005, after completing probation, Reddy successfully petitioned the court to set aside his conviction. The benefits of that expungement include not having to disclose convictions on job applications.

The next year, Reddy filed for reinstatement of his medical license and, at a hearing, admitted that he’d been untruthful in denying the acts of sexual misconduct, board records state. He said he accepted responsibility for his misconduct after going through “a long healing process” that included psychotherapy.

The board denied his petition in 2008. Two years later, Reddy filed another petition and submitted evidence that he had completed a program called Sex Offender Solutions, with more rigorous testing, including polygraphs and penile plethysmography, which measures sexual arousal.

The sex-offender therapist testified that Reddy had been rehabilitated and “does not suffer from a mental disorder that predisposes him to sexual crimes.”

Reddy expressed remorse, according to Medical Board records.

The battle between would-be reformers and the California Medical Assn. gained fresh momentum this week in the wake of a Times investigation that found the Medical Board of California consistently allowed doctors accused of negligence to keep practicing.

“I now acknowledge that what I did was wrong,” he said. “I broke the trust of my patients. I feel terrible about it. I feel humiliated. Under the guise of providing medical care, I exploited patients for my own sexual interests.”

The administrative law judge and a deputy attorney general agreed that Reddy’s petition should be granted. The Medical Board reinstated his license in 2012 and placed him on probation for seven years.

He completed probation in March 2019, and his license was fully restored a year later.

Neither Reddy nor his attorney in the reinstatement proceedings responded to repeated requests for an interview. When contacted in person at Desert Valley Hospital in Victorville, where he works, Reddy declined to comment.

Melissa Cardoza was 29 when she went to Nadjmabadi, the Bakersfield internist, in 2005 for a shoulder injury suffered in a wakeboarding accident.

He did a lot of sick things to me. He is a sick man.

— Melissa Cardoza

Alone with him in the exam room, he told her to pull her jeans and underwear down a little so he could examine her. He had her bend over and touch her toes as he stood behind her, according to board records.

Then he told her to remove her jeans and underwear from her right leg, exposing her genitals, and touched her inappropriately, according to board records and a lawsuit she filed.

Nadjmabadi scared her into thinking she might have colon cancer, Cardoza told a Times reporter in a recent interview. She didn’t need to see another doctor, he assured her; he could do the necessary exam himself. He also offered to do a Pap smear, which is usually performed by a gynecologist to check for cervical cancer. There was never a medical assistant in the room during any of the exams, Cardoza said.

“He did a lot of sick things to me,” Cardoza said. “He is a sick man.”

When reached outside the Bakersfield clinic where he works, Nadjmabadi declined to answer questions, saying, “That’s ancient history; it’s over. I’ve moved on with my life. Life is good.”

Ramirez, who saw Nadjmabadi for the spider bite, immigrated to the U.S. from Guadalajara in 2004 with her husband and three daughters. She said she felt safe seeking medical attention from Nadjmabadi because she had befriended his wife while living in Bakersfield.

There was no one else in the exam room when she showed him the dark-brown spider bite behind her left knee. Ramirez said she felt disoriented during the visit from medication prescribed by another doctor for the bite.

Nadjmabadi asked her to remove her pants and shirt to check for any other bites.

“I’m sorry, I’m just very meticulous,” she recalled him telling her repeatedly.

When she returned for a follow-up visit, Nadjmabadi insisted he check her for colon cancer.

“You’re in a country that’s not yours, you don’t know another doctor, you’re trusting in what the doctor tells you,” Ramirez told The Times.

While the two were alone in the room, Nadjmabadi coated his fingers in lubricant and put one in her vagina and another in her anus, according to Ramirez and the board accusation. She recalls him asking at one point if she felt comfortable.

“In addition to feeling physically terrible, I felt horrible emotionally,” she said. “I was in shock.”

When she got home, Ramirez said, she cried until exhaustion forced her to stop. She immediately showered, feeling dirty.

“This was abuse, and he’s going to pay,” Ramirez thought to herself. “He needs to know that I know what he did.”

Her complaint to police, and the ensuing Medical Board investigation, forced Nadjmabadi to surrender his license in 2010.

For Nadjmabadi, admitting that his accusers were telling the truth when he applied for reinstatement was an abrupt about-face. He’d previously insisted that they were liars, including the claim in a lawsuit against the board demanding the return of his license that he appealed to the state Supreme Court — to no avail.

At his 2015 reinstatement hearing, he introduced a report from therapists who had evaluated him.

Nadjmabadi said he had always been a “goody two shoes,” according to the report, but he had become “a little bit heady with the power of being a well-respected ... provider in the community.”

Nadjmabadi, who was married, was shy with the opposite sex, the therapists found. “He has had very little experience dating women and therefore is not well versed in the language of bantering and seduction,” they wrote. “He now realizes he misread some cues during his interactions with these patients and that he may have perceived consent where none was given.”

But once Nadjmabadi began abusing his female patients, he started asking himself “how far he could go,” the therapists reported.

They concluded that Nadjmabadi was “appropriately remorseful” and had done his best to “make amends” but also recommended that he have “a chaperone in attendance during all interactions with female patients.”

H. Stuart Waxman, the administrative law judge who heard the case, determined that Nadjmabadi had matured sufficiently to resume practicing medicine: “He no longer views his position as one from which he can control his patients, but as one from which he can serve them.”

Nadjmabadi’s license was restored in 2015.

That came as a shock to Ramirez, who had left Bakersfield to avoid ever running into Nadjmabadi or his wife. No one from the Medical Board contacted her — or any of the other accusers — beforehand.

“If they had asked us, I don’t think he would have gotten his license back. We all would have been against it,” she said. “I have three daughters. I’m not going to risk a man like that touching them inappropriately.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.