Inside the hunt for a killer who shadowed a homeless camp

Even in Los Angeles County, where hundreds of people are murdered each year, the three killings in a homeless encampment along the banks of the Compton Creek stood out.

In death, the victims came to underscore the precarious, dangerous existence of homeless people in the county. Like many others scraping out lives on the streets, they were in the grips of drug abuse or mental illness. And they belonged to a population that disproportionately falls victim to homicides and other violent crimes.

But little was known about their killer, other than the fact that he too was homeless. Now, through court records and interviews with his attorney, a detective who worked the case and others, a portrait comes into focus of a man submerged in a solitary, paranoid existence, who saw people either as “predators” or “prey.”

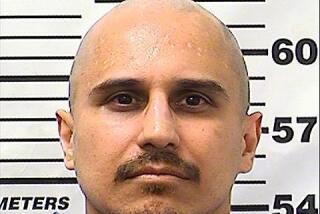

Tracy Walker does not dispute his crimes. He pleaded guilty to the three murders and recently was sentenced to 110 years in state prison. Ineligible for parole, Walker will die there.

After he was arrested, Walker talked to Los Angeles County sheriff’s detectives about the killings. His victims, he claimed, had trespassed in his tent, stolen his possessions, even held him up at gunpoint. He had been left with no choice but to defend himself, he claimed.

Detectives collected some evidence that suggests otherwise. They concede they’ll probably never know if they’ve learned the full story of why Walker killed or merely the one he chose to tell.

Three people were killed along Compton Creek in the last year. Their killer, authorities say, was a man who lived in a homeless encampment along the creek.

*

Walker was born in 1964 in Mississippi, according to a probation report reviewed by The Times. He was one of about eight brothers, most of them born to different fathers, said his attorney, Kelly L. O’Brien.

Walker, 57, declined an interview request but asked his lawyer to speak on his behalf.

When he was 21, Walker left Mississippi for Los Angeles, where he found work as a security guard. While watching over a bus yard on 77th Street in South Los Angeles early one Saturday morning, he got into a dispute with another guard and fatally shot the man, according to his lawyer and a 1991 Times report. He fled the scene in a yellow school bus.

A pair of officers from the Los Angeles Police Department stopped the bus on San Pedro Street and ordered Walker out. When Walker reached for his gun, the officers opened fire, police officials said at the time.

Walker was shot several times and spent months in a hospital. About a year later, he pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to 16 years in state prison, according to probation records.

In prison, Walker was diagnosed with “a gamut of different mental health issues,” his lawyer said, including schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from being shot by the police. At one point, Walker was declared “mentally disturbed,” a probation officer wrote in a report. He received some mental health treatment in prison.

“Clearly,” O’Brien said, “it was not enough.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Walker was released in 2001. He had been married before his stint in prison; by the time he was freed, his wife had left him and moved out of California. He was estranged from other relatives, his lawyer said.

Walker worked as a janitor, laborer and security guard, according to a probation report. His mental illnesses, however, kept him from holding a steady job, O’Brien said. “He went from a highly structured environment in prison to no structure.”

Walker became homeless soon after he was released from prison, according to the probation report. Living on the street, he developed what his lawyer called a sense of “hyper-vigilance.” He carried a knife — for protection, O’Brien said — and was arrested on suspicion of possessing the weapon in 2011.

“We can go to our homes and lock our doors at night,” O’Brien said. “He has to sleep with one eye open.”

After living on downtown Los Angeles’ skid row and then near a social services building in Compton, Walker moved to the Compton Creek. He would tell detectives later he had been looking for seclusion, a place where the police and other homeless people would leave him alone.

A waterway entombed in concrete that winds through freight yards and warehouses in Rancho Dominguez before emptying into the Los Angeles River, the creek offered Walker a measure of solitude. A few people, but not many, pitch their tents in the shadows of the trees along the creek’s eastern banks and in a nearby clearing for Pacific Harbor Line train tracks.

It was along the tracks that an engineer for the railroad company found a body one evening in June 2020.

Gustavo Carrillo and Daniel Machuca, homicide detectives from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, got to the tracks about 11:20 p.m. Patricia Loeza, 26, was lying on her back, her legs covered with a gray wool blanket. She had been dead for some time.

The youngest of four siblings, Loeza was raised in South Los Angeles by her mother after her father was deported to Mexico, family members told The Times. She began using drugs in high school and soon was cycling in and out of juvenile institutions, the relatives said. She disappeared for long stretches, sometimes because she had been sent to jail, sometimes because she was living on the streets.

A juice carton and receipt found next to Loeza’s body led Carrillo and Machuca to a grocery store in Long Beach. After identifying a possible suspect on footage from one of the store’s security cameras, the detectives showed images of the man to homeless people living near the creek.

At an encampment near Del Amo Boulevard and the 710 Freeway, one person said he recognized the man in the picture. His name, the person at the encampment told the detectives, was Solo. He stayed away from other people and didn’t get along with anyone.

Loeza’s sisters, meanwhile, had decided to take the search for her killer into their own hands. They walked along the Compton Creek, looking for evidence and witnesses. After finding a long kitchen knife and other knives in a tent, they called Machuca and asked him to meet them at the creek, according to an affidavit the detective wrote in seeking a search warrant. Machuca declined to be interviewed for this article.

As they were talking, a man approached them and said, angrily, that his tent had been rifled through and vandalized. Machuca recognized him from the grocery store video.

The detective calmed him down and asked his name.

“They call me Solo,” he said.

Carrillo and Machuca reached out to a team of deputies at the sheriff’s station in Carson who patrol homeless encampments. The deputies knew Walker well, Carrillo recalled. He kept to himself and didn’t cause problems.

A psychiatrist the detectives consulted recommended one of them try to slowly build a rapport with Walker. Because he had already spoken with him, Machuca was the logical choice. He ditched the suit and tie he customarily wore as a homicide detective for a deputy’s traditional khaki uniform. A Carson officer who knew Walker re-introduced Machuca to him as “just another deputy,” Carrillo said.

Machuca and the suspect talked about Walker’s life on the street — where he’d lived before, why he’d come to the creek. In subsequent visits, Carrillo said, Walker expressed an interest in reading, so the two talked about books. Sometimes the detective would bring him a hamburger. Each time, he’d ask about the woman found dead near the creek; each time, Walker would say he didn’t want to talk about it, Carrillo recalled.

Six months went by. Then Kenneth Jones was found dead.

Jones, 26, had struggled with drug addiction since he was a teen. He flitted for years between living on the streets, in a home operated by a church and with relatives. Jones shoplifted and stole bicycles to support his addiction, according to a relative and a probation report. His girlfriend told the police that the bicycle thefts angered some people, the probation report said.

The afternoon of Jan. 15, a homeless woman found Jones’ body on a bank of the Compton Creek.

A different pair of detectives were assigned to investigate Jones’ death, but Machuca and Carrillo suspected Walker may have killed him, Carrillo recalled. There were similarities to their case, but also differences: Jones’ body was found not far from Loeza’s, but he had been beaten over the head; Loeza had been stabbed.

“It was just a hunch,” Carrillo said.

Three weeks later, Carrillo got a call from the Carson station deputies: Another body had turned up at the creek.

Cesar Mazariegos, 30, had struggled to find work since being released from prison 11 months earlier, his mother recalled to The Times. He’d report to a staffing agency near where the Compton Creek flows beneath Del Amo Boulevard, hoping to pick up work loading and unloading retail goods at warehouses, his mother said. He slept at friends’ homes, motels and sober living centers.

Mazariegos was found beneath a pile of tumbleweeds, a piece of carpet and a canvas tent. Sheriff’s detectives asked Walker if he knew anything about the death. Describing himself as a “loner,” Walker said some members of the Eastside Longos gang had thrown a “meth party” the previous evening, but he denied knowing anything about a murder, a probation report says.

Two days later detectives found footage from a security camera that showed Walker using a furniture dolly to roll “an odd-shaped heavy object” into a wooded area and then return later carrying a tent, a large piece of carpet and several tumbleweeds, a deputy wrote in an affidavit seeking a warrant to search Walker’s tent and a storage unit he rented near the creek.

In the unit, they found bicycles, dollies, shopping carts, four pairs of bolt cutters, stained clothing, six cellphones, a safety deposit key, a blue bandana, a black “Long Beach” hat, a “Malcolm X textbook containing handwritten writing” and about 50 knives, according to search warrant returns and a probation report.

Detectives arrested Walker, who denied killing anyone. He grew angry when a detective said they considered him a “cold-blooded killer” and refused to speak with them, according to a search warrant affidavit.

The next day, Machuca and Carrillo drove to the Carson sheriff’s station. Walker recognized Machuca immediately, and started talking.

“He’s still telling us the same story,” Carrillo recalled: He didn’t do anything wrong. He didn’t kill anyone. Walker was adamant that if they tested a knife seized from his tent, they’d see it wasn’t used to kill Mazariegos.

The detectives read him his rights and let him talk. Wanting to preserve the rapport that Machuca had built with their suspect, Carrillo was the one who delivered the bad news. He told Walker detectives had searched his storage unit.

Carrillo asked Walker what he thought they’d found. “They found something in that storage to incriminate me for a PC one-eighty-seven,” Walker said, according to a search warrant affidavit.

One of the items seized from the storage unit, Carrillo said, was a copy of California’s penal code. Section 187, the section of the code that spells out the crime of murder, had been highlighted, the detective recalled.

“It’s all over,” Walker told them. “I’m remanded in custody and it’s gonna be a plea bargain agreement. Life without the possibility of parole or death penalty.”

From that point on, Carrillo said, Walker was “completely open and honest.” Machuca asked the questions. “All I did was sit and nod my head, up and down. I just agreed with whatever he was saying, stayed sympathetic.”

They showed Walker a photograph of Loeza. Walker said he had caught the woman inside his tent, stealing his belongings. Her last words, he recalled, were: “I’ll give you everything I got.” Walker said he responded: “If I catch you wrong, it’s up to me to teach you a lesson. I’m dangerous prey.”

They showed Walker a photograph of Jones. Walker said he’d found Jones using a pair of bolt cutters to steal his bicycle. Before he went to sleep, Walker chained the bicycle to his tent so he could feel it shaking if anyone were to steal it, his lawyer said.

Jones was walking away with the bicycle when Walker ran up to him and stabbed him in the chest, he told the detectives. In the ensuing struggle, Walker put Jones in a headlock, “trying to break his f— neck,” he said, according to a probation report that quotes his interview.

Jones bit Walker’s left hand, and Walker said he “bashed his f— skull in” with the bolt cutters, according to the report. He dragged Jones’ body into the bushes and tossed the knife in some weeds. He wiped the bolt cutters clean of Jones’ blood and hid them in his storage unit.

When Jones tried to steal his bicycle, “he was f— with dangerous prey,” Walker told the detectives. “He just didn’t know it.”

Walker then asked to see a photograph of “the Eastside Longo.” Shown a photo of Mazariegos, he said he had returned to his campsite from a trip to the storage unit when Mazariegos confronted him with a Tec-9 handgun and tried to rob him. By the way Mazariegos handled the gun, Walker could tell that he wasn’t familiar with it, he told the detectives.

Walker said he rushed Mazariegos and wrestled the gun away from him; at this point, he got down on the floor of the interview room and demonstrated how the two had struggled, Carrillo said. When he was done, Walker sprang to his feet “like an offensive guard,” the detective recalled. He and his partner were startled, almost unnerved, by the quickness shown by their 6-foot-1, 360-pound suspect.

*

“If Tracy is telling us the truth,” Carrillo asked, “if these ‘predators,’ as he called them, didn’t do what he said they did to him, would he have killed?”

Parts of Walker’s story were backed up by evidence. He told detectives, for example, where he had buried the gun he said he had wrestled from Mazariegos. Deputies dug up the weapon and confirmed Mazariegos was carrying the same type of gun before he was killed, according to a probation report.

Of course, Carrillo noted, Walker is the only one alive to tell the story. He might be an unreliable narrator, having killed the only people who could contradict his version of events.

And then there were the “trophies” that Walker said he took from “battle” and “warfare.” He kept them in his storage unit: a Cricket Wireless cellphone from Loeza, the bolt cutters from Jones, a blue bandana and black “Long Beach” hat from Mazariegos.

“This is an individual who has killed before,” said Deputy Dist. Atty. Hilary Williams, who prosecuted Walker. “He has now killed three additional victims — that we are aware of — and he keeps a trophy, a token if you will, from each of his most recent victims. It’s hard to reconcile that with the idea that he’s prey, that he’s being victimized, that he had to act in self-defense.”

Once Walker told them he kept “trophies,” the detectives examined the other trinkets he kept in his storage unit — in particular, six cellphones and several ID cards in other people’s names. The phones, Carrillo said, were either too old or too damaged for a tech team to download their contents and learn to whom they had belonged. Detectives determined that the people whose ID cards ended up in Walker’s unit were all still alive. They assume he either found the cards or stole them.

The detectives also had tested all 50-some knives seized from the unit for human blood, Carrillo said. None came back positive.

They asked Walker if he had killed anyone other than Loeza, Jones and Mazariegos. He said he had not.

“At this point, we have no other cases to link him to,” Carrillo said. “As far as we’re concerned, this is it. These are the only three he’s done. That’s not to say that couldn’t change.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.