For poor farmworkers, there is no escape from heat, high prices of California

BORING, Ore. — For 24 years, Jaime Villegas left his mobile home in the Central Valley every summer to follow a path paved by generations of California farmworkers.

He would get into a car packed with duffel bags of clothes and coolers with food and embark on a 14-hour journey through acres of agriculture fields, past giant sequoias and unmarked dirt roads to their final destination: Oregon’s blueberry harvest in a town called Boring.

He was a boy when he first started doing this trip with his parents, and in later years he went with his wife, Enedina Ventura, and their children. But the ritual was almost always the same. Friends would run into each other on the way up north. The fathers drove the cars; mothers helped in the fields while children attended school until they were old enough to help with la cosecha.

“It felt nice,” Villegas, 38, said on a recent October evening. “The good thing is family supports you.”

But that ritual has been upended. Fewer and fewer Californians are now showing up for the blueberry harvest. Experts and farmers say economics and a lack of affordable housing are largely to blame.

But it’s not the only reason. A place Villegas and Ventura and so many other farmworkers considered relatively pleasant to pick is no longer the same.

Summers in the Pacific Northwest are getting hotter and drier. Oregon’s temperatures have skyrocketed to triple digits in recent years. Several blazes, including the Bootleg fire, raged throughout the Beaver State.

Edward Taylor, distinguished professor at UC Davis’ Agriculture and Resource Economics department, said to his knowledge there isn’t a study that statistically links harvest migration to extreme heat in the Pacific Northwest. But he found it interesting and worth studying because whatever makes migration less attractive makes people migrate less.

Taylor conducted research in Mexico that showed extreme heat “significantly” drove migration out of rural communities and into other parts of Mexico and the United States.

“I can imagine in this context that anything would make farm work less pleasant than it already is,” said Taylor, who also serves as director of the Center on Rural Economies of the Americas and Pacific Rim at UC Davis. “It would simply compound this big picture we see happening out there. Fewer farmworkers. Less and less are willing to migrate to follow the crop.”

“We can ban pesticides, but we can’t ban hot weather,” said Dr. Marc Schenker, distinguished professor emeritus of public health sciences and medicine at UC Davis and founding director of the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety. “We can’t regulate Mother Nature.”

In this last summer harvest, in their Boring camp, Villegas and his family cooped up in a bedroom and could hardly sleep. Others felt the same. Some left their bunks to nap under a tree outside. The portable fans ranchers provided blew hot air.

At work, they toiled in 115-degree weather. They worked as fast as possible but couldn’t fill their tin buckets with berries. So many had overripened in the sun.

“Ay Dios mío,” Ventura asked herself. “¿Que está pasando?”

What’s happening?

The couple are part of a shrinking breed of farmworkers.

Anne Krahmer-Steinkamp, a sixth-generation berry farmer in Albany, Ore., said five years ago she employed nearly 200 Californians from Madera, Stockton and Watsonville who arrived to Krahmer-Steinkamp’s farm through phone calls made by her supervisor, Eloy Garcia. This year, only 10 Californians committed to the harvest.

Her workers — once 80% Californians, now about 20% — had been picking for just four days on the 300-acre blueberry farm before triple-digit temperatures set in. She pushed up their morning shift and told them to pick as much as they possibly could. “We set them loose and just flew,” she said.

By the second day of extreme heat, Krahmer-Steinkamp said she had lost 15% of her crop. She was lucky; other local farmers lost their entire harvest.

Villegas started working in the fields in the late 1990s. His family left their hometown of San Miguel Cuevas in Mexico’s Oaxaca state and headed north for better-paying jobs. In the Central Valley, he picked grapevine leaves until his father announced they would all travel farther north to work.

Oregon was a big change compared with the valley. Douglas firs were everywhere. It seemed as if it never stopped raining.

The first year in Boring was challenging. At the time, the Villegas family didn’t have enough money to purchase raincoats or rain boots. They donned a cap, dressed in layers and cut holes in giant black plastic bags to keep their bodies somewhat dry.

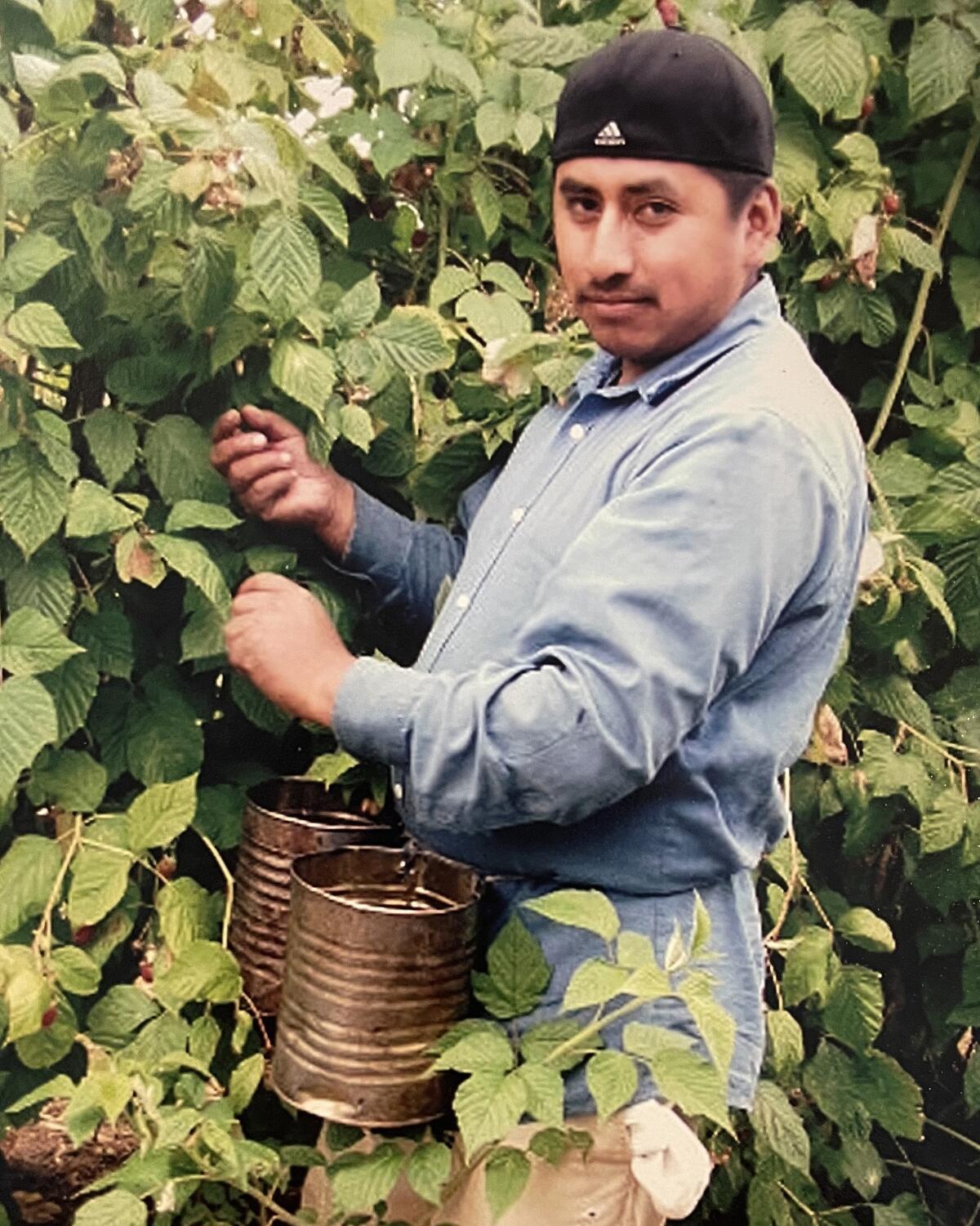

Villegas trudged through the mud, lugging two tin buckets strapped around his waist. His numb fingers clumsily plucked berries off twigs. Rain thudded against his body as he made his way down rows of blackberry bushes.

“It used to get so cold here, the fruit froze,” he said.

Ventura remembers those days as well. She first arrived in Oregon as a 13-year-old, after living in Fresno for a week. Ventura’s older brother lived and worked in Oregon for years and showed her the sights before the strawberry harvest.

“It was very difficult,” Ventura, 32, said as she watched her daughter play in the living room back in Fresno. “In that time, there was so much rain. Day and night, rain. Day and night, more rain. It rained and we just had to keep working and we would get so dirty.”

The work presented new challenges when she became a mother. She woke up earlier, preparing breakfast at 4 a.m. and getting her children ready for school before dawn. Then, she was off to work with Jaime.

But Oregon’s greenery and weather were a reminder of her hometown in San Miguel Cuevas — a mountainous place with dirt roads, lush greenery and fog blanketing the area. She returned every summer to Oregon after her first visit, where she met Jaime.

Ventura spoke fondly of the pine trees and chilly weather — a stark contrast to her Fresno home. “I also like it because I see nature more than I do here,” she explained. “It’s city life here, but out there I see so many trees and pines and I feel like the air is different.”

How Oregon has changed since she fell in love with its charm.

This year, Oregon was hotter than any place in the United States except for Death Valley, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting. At least one farmworker died from heat-related causes while working in June at a nursery in St. Paul, a tiny city in the northern part of the state.

“2021 was a storm for disaster,” Krahmer-Steinkamp said.

Garcia, her supervisor, said it became harder to find farmworkers willing to travel from California.

“They say, ‘I want to be there and help you, but can you find a room for me and my friends?’” he said. “I did that before … but I stopped because sometimes I lost my money. They promised me, ‘Let me finish my job here and I pay you money at end of the season.’ And they left a week before the end.”

“We go because it’s too hot here in the summer and the weather is beautiful there. But now, what’s the point in going if it’s the same as here?”

— Enedina Ventura

Villegas and Ventura, who eventually had four children, noticed the familiar faces they had seen over the years dwindle at camp.

Workers could no longer afford to rent rooms. Some grew too old to make the journey. Some stayed permanently, lured by the still-cooler weather compared with the Central Valley. Some left the fields to take on other jobs, marking another trend seen in farm work nationwide, where younger generations are opting for better-paying jobs.

About a mile down the road from Krahmer-Steinkamp’s farm, Oscar Cruz saw the long-held tradition wane within his own family.

In 1992, Cruz left his home in Costa Rica, a town in Mexico’s Sinaloa state, to follow the strawberry harvest in Oregon, where he permanently settled. In the fall, he migrated south to California to pick olives and visit family members before returning to work at home. Back then, he said, 500 people arrived in Oregon ready to work even if it meant sleeping in their cars for weeks.

He loved the tranquility of working in the fields and hoped his children would one day follow in his footsteps. And for a few years, his family joined him.

But the adventures stopped after four years when his family craved a stable life. Cruz became a ranch supervisor at an Albany blackberry farm, overseeing workers. When two of his daughters and one son picked blackberries, only one daughter, Sarai, 20, fell in love with the work.

Another daughter, Cruz said, couldn’t handle the heat. Instead she’s studying nursing at Clackamas Community College. His son is considering returning one day for the money.

Villegas and Ventura hope their children will pursue something greater. If given the chance, the couple said they would’ve pursued different jobs.

After this year’s sweltering season, the couple are unsure whether it’s worth continuing their Oregon run.

“We go because it’s too hot here in the summer and the weather is beautiful there,” Ventura said from home in Fresno. “But now, what’s the point in going if it’s the same as here?”

Aware of the lack of work, the Boring rancher begged them to not move on to another farm, the couple said. Their boss, they said, asked them to pull weeds and organize materials in hopes the next crop would yield better results.

“It’s only going to keep getting worse the way we’ve been treating our planet,” Villegas said.

The rain attire they purchased long ago is no longer necessary. It’s always packed in their duffel bag, but it’s never worn.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.