Lee Vining, Calif. — For those who live near the briny shores of California’s Mono Lake, October can be a dreaded month. That’s when turbulent winds scour Mono’s exposed lake bed, or “bathtub ring,” and launch clouds of fine dust that blanket homes, ranch lands and scenic trails.

For 50 years, the vast lake has been a source of so-called PM10 particulate — a dust so fine that it can clog human airways, penetrate the lungs and aggravate serious heart and lung diseases, such as asthma.

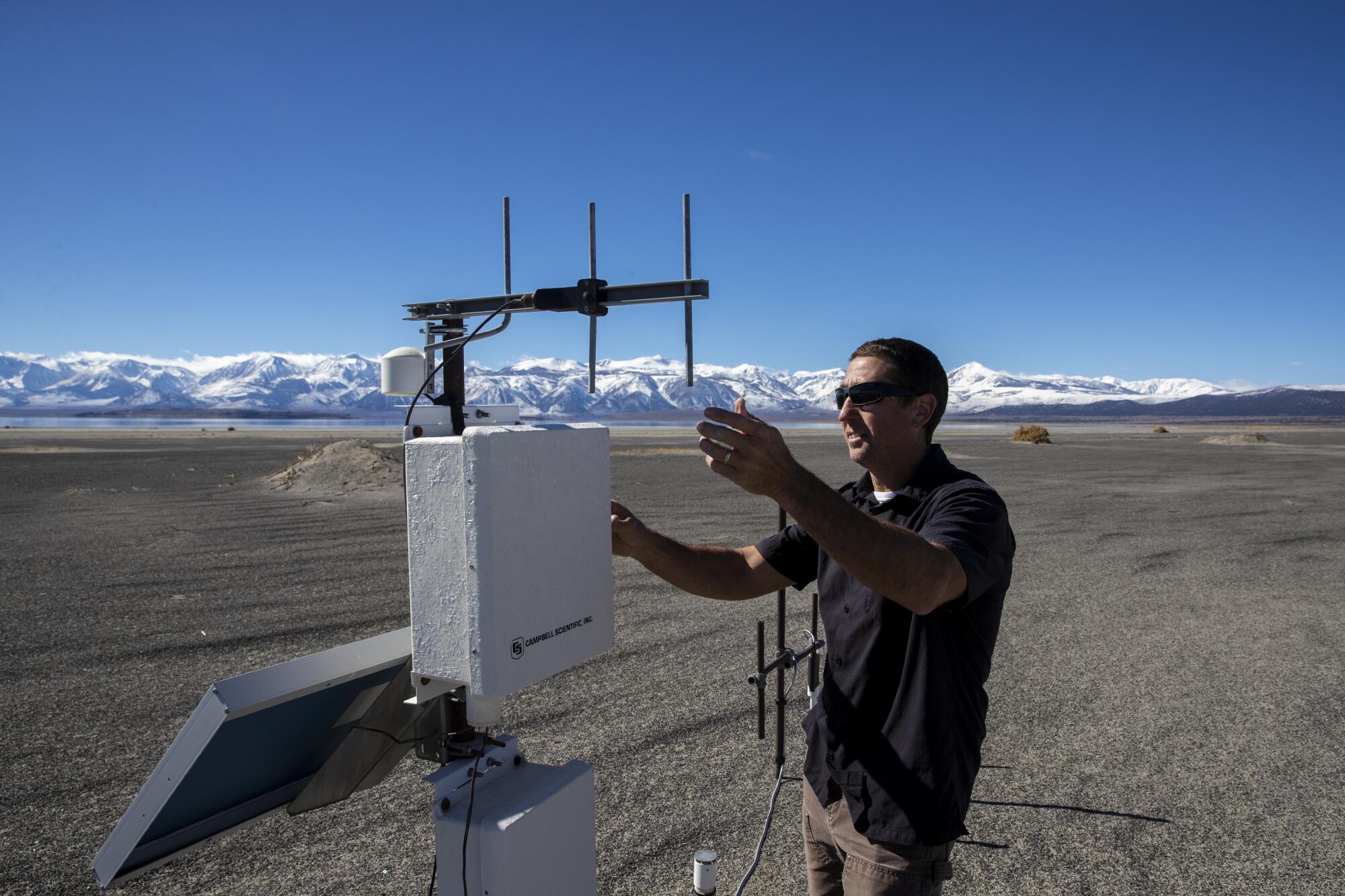

“We’ve got a public health crisis on our hands,” grumbled Phil Kiddoo, enforcement officer for the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, which oversees a battery of monitoring devices that help chronicle the dust storms rolling off Mono Lake this time of year.

Kiddoo and others have long blamed the city of Los Angeles for generating this pollution hazard. Ever since World War II, the city has diverted water from the streams that feed into the lake on the arid eastern side of the Sierra Nevada range. Without an adequate source of replenishment, critics say, the lake has been left to slowly shrink, exposing more and more of its alkaline lake bed to the air.

Now, after two years of punishing drought, Mono County conservationists, tribal leaders and air regulators have launched a campaign to raise the level of the lake. They hope to accomplish this by stopping the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power from diverting water from the lake’s feeder streams.

The campaign hinges on the novel argument that Los Angeles can afford to stop diverting water here because Angelenos are now experts at conserving water.

For its part, the Department of Water and Power said Mono County officials should first study whether the dust is coming from somewhere else before they cast blame.

Mono officials such as Kiddoo have often spoken of possible legal action in the long-running dispute, but so far they have not resorted to the courts. Recently, however, a coalition of 18 environmental groups and the Great Basin district sent correspondence to the DWP saying that Los Angeles was conserving so much water that it could afford to stop diverting from Mono Lake’s feeder streams.

They pointed out that water use within the DWP’s service area has dropped by 22% since fiscal year 2013-2014, according to the DWP’s water management plan. Also, about 4 million Angelenos currently use 40 gallons less per person per day than they did 15 years ago, even with drier conditions.

The DWP has attributed those achievements to strategies including storm water capture, groundwater replenishment, recycling, low-flow toilets and $2 billion worth of court-ordered dust control projects at dry Owens Lake, about 140 miles to the south. Those projects use gravel, vegetation and other methods to keep dust down at Owens Lake, instead of using large amounts of water.

Mono County officials say these measures have saved the DWP more than twice the 16,000 acre-feet of water the city typically exports from the Mono Basin in a year.

“The time has come for the city to share its conservation benefits,” said Wendy Schneider, executive director of the nonprofit environmental group Friends of the Inyo. “Lives and ecosystems are at stake.”

Regional air quality officials, environmental groups and Native American tribal leaders have asked the DWP and its commissioners to enter discussions at reducing, or even halting, the diversions to minimize the city’s “potential exposure to liability and litigation that would most assuredly ensue should a more adversarial approach be taken.”

Anselmo Collins, a senior assistant general manager for the DWP’s water system, responded in a letter late last month that said the agency’s “ability to meaningfully engage” in such discussions is limited without more data and analysis of all possible sources of pollution that potentially affect air quality in the region.

With that goal in mind, Collins encouraged the Great Basin district to investigate potential off-lake sources including “burn scars resulting from wildfire, wild horse impacts, and the historic fluctuation” of lake levels “that pre-date LADWP’s diversions.”

Famous for its towering, craggy tufa formations, Mono Lake is a remnant of a vast inland sea, where fresh alpine snowmelt cascading from Sierra slopes combines with salty water that is home to brine shrimp and swarms of alkali flies that provide nourishment to migrating birds including an estimated 50,000 California gulls.

The controversy over Los Angeles water diversions from Mono’s feeder streams is one of California’s longest-running environmental battles.

By the late 1970s, tributary streams had dried up, dropping the lake level more than 40 feet and doubling the water’s salinity. What followed were smelly salt flats and choking dust storms.

Formal protests began with a lawsuit that a grass-roots coalition of residents and environmental groups filed in Mono County Superior Court in 1979 against the DWP. The suit alleged violations of public trust and the creation of a public and private nuisance by exposing 14,700 acres of former lake bed.

The breeding cycles of Western gulls became a touchy political drama for L.A. when a plummeting water level revealed a land bridge connecting an island rookery to the shore, allowing coyotes to pad across and feast on the birds and their eggs. The Army Corps of Engineers tried to blow up the land bridge with dynamite, but the muck only exploded sky high, then fell back in place.

In 1983, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand a ruling that environmentalists had the right to challenge the amount of water L.A. was exporting from the tributaries. A decade later, the state water board established rules for the DWP’s water exports from the Mono Basin.

When Mono Lake is between 6,380 and 6,392 feet above sea level, the DWP can export 16,000 acre-feet of water a year. If the lake drops to between 6,377 and 6,380 feet, the DWP’s exports are reduced to 4,500 acre-feet of water a year. If the lake is below 6,377 feet, the DWP cannot export any water.

Once Mono Lake rises above a target level of 6,392 feet above sea level, the DWP will be allowed to export all water in excess of required tributary flows of 89,000 acre feet.

Since 1994, the lake level has fluctuated between roughly 10 to 12 feet below that target level.

“The journey to raise the lake to a healthy level isn’t on schedule and the consequences are dire,” said Geoffrey McQuilkin, executive director of the Mono Lake Committee, a nonprofit that sprang up in the 1970s to try to forestall the death of the lake.

Recently, the state water board approved a 2013 voluntary agreement aimed at healing the damage to streams caused by L.A.’s diversions.

The plan is to release pulses of water from an earthen dam along a seven-mile stretch of Rush Creek to mimic annual flood cycles, distributing willow seeds and promoting healthy trout populations.

But the agreement does not affect water diversions, nor will it affect the height of the lake. Even now, declining water levels during the current drought are exposing more alkaline lake bed and threatening to again uncover a land bridge connecting the island rookery for one of the world’s three largest California gull colonies.

A mile southeast of the small mountain town of Lee Vining, a gateway to Yosemite National Park, there is a stretch of crusty shoreline where Mono Lake Committee staffers and DWP officials gather each year in early April to read a lake level gauge at the start of the new runoff year.

Maureen McGlinchy, a hydrology modeling specialist for the committee, visits the site at least once a month to gather all the information with binoculars, water sample bottles, a notebook and a gadget that measures wind speed, ambient temperature and relative humidity.

On Oct. 26, she reported the lake’s surface elevation to be 6,379.85 feet above sea level, or 12.15 feet below the target level.

“If recent hydroclimate trends continue into the future and L.A. continues to divert water from the area, Mono Lake’s recovery will remain stalled,” she said. “If, however, L.A. stops its diversions, Mono Lake would reach the target level within 20 years.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.