On a sweltering Saturday last month, Sheryl Bell looked around the banquet room at the Morongo Golf Club at Tukwet Canyon in Beaumont.

Before her, about 75 people enjoyed a taco lunch after a morning round of 18. Behind Bell, tables groaned with items donated for an auction: lithographs, coffee machines, vintage Mickey and Minnie Mouse plush dolls. Toward the back of the room was a small display in honor of her late son, Julian Alexander.

“I hope you had the chance to at least read the bio about Julian,” she said, gesturing to the pamphlets on each table.

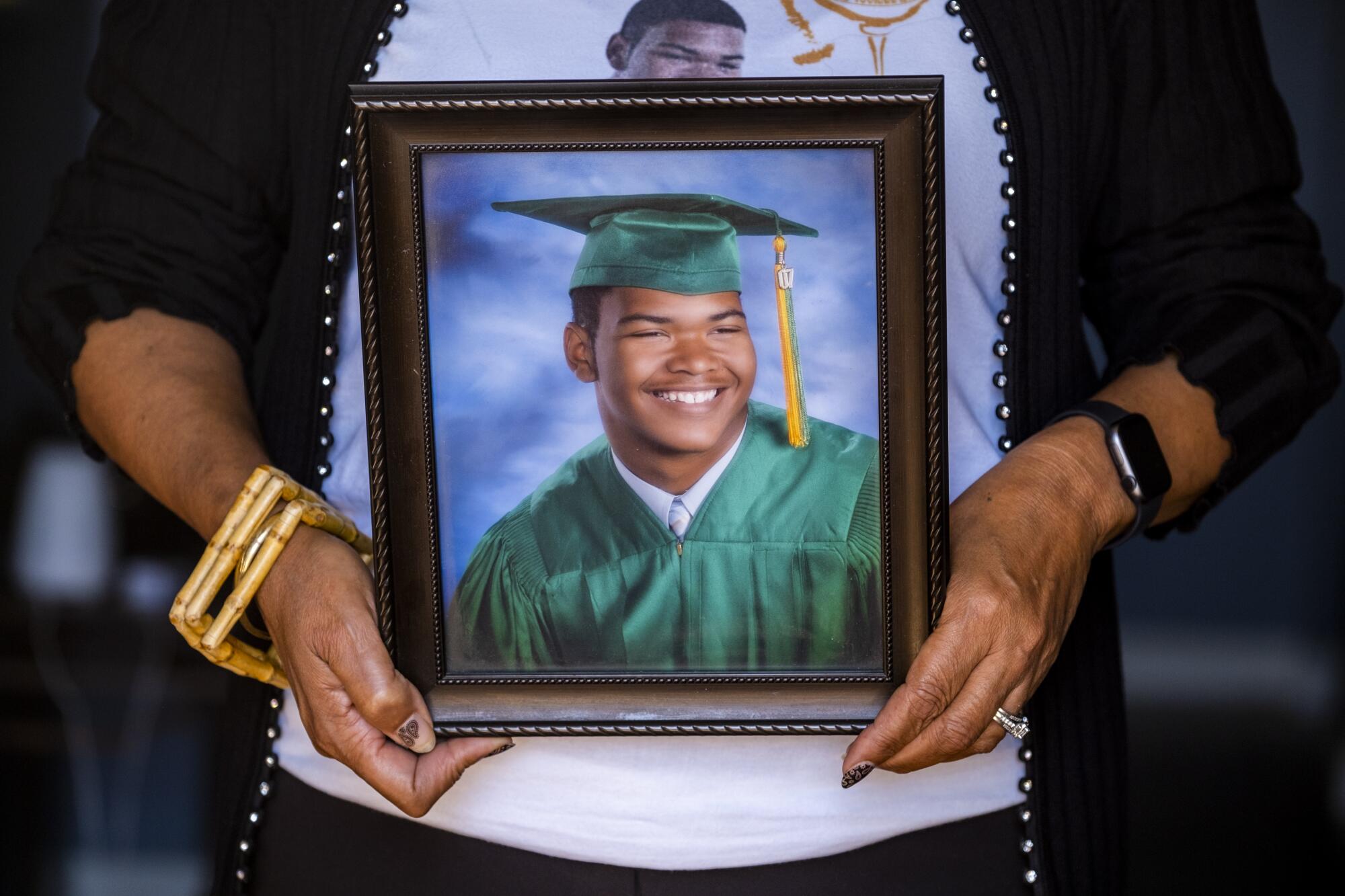

The Julian Alexander Memorial Golf Tournament, it read, has awarded more than $75,000 in scholarships to high school seniors since 2009. The front page featured a photo of him, smiling and sitting while showing off his letterman jacket from Notre Dame High School in Riverside.

“He was a beloved son, new husband, and soon to be father,” the inside page read, just after it listed his cause of death: An innocent man killed by an Anaheim police officer.

In the early morning of Oct. 28, 2008, Alexander awoke after he heard a noise outside the home of his in-laws in Anaheim. He and his wife had married just a week earlier, a day after Alexander’s 20th birthday. The two were expecting a child that December.

Alexander went out to the front yard with a broomstick to investigate the commotion. Men were fleeing Officer Kevin Flanagan, who suddenly stopped when he saw Alexander. The 10-year veteran told Alexander to drop the broomstick, then shot him twice when he didn’t, killing him.

Anaheim’s police chief at the time called Alexander’s death “tragic” but kept Flanagan on the force. The Orange County district attorney cleared him of any wrongdoing, stating in a report that Flanagan felt threatened and was thus justified to kill.

Today, the police slaying of a Black man or woman would spark protests, national news coverage, another bout of soul-searching. But Alexander’s death, just days before the historic election of Barack Obama, barely registered outside of those who knew him. It never galvanized the public the way the killing of Michael Brown did. Or that of Sandra Bland. Oscar Grant. Breonna Taylor.

“We were beginning to have grown-up talks. About fatherhood. About being a good husband. A good man. A good son.”

— Sheryl Bell, mother of Julian Alexander

Bell mostly grieved privately for 13 years, with this golf tournament the one prominent, persistent statement about the killing of her son that she was comfortable with. But in the wake of George Floyd’s murder last year, a new generation began to commemorate Alexander’s life.

A downtown Riverside mural dedicated to people slain by gun violence included him. An artist added Alexander to a poster that commemorated Black men and women killed by police under the legend “Say Their Names.” Activists said his name at Black Lives Matter rallies in Fresno, in Orange County, in San Diego. The upcoming Civil Rights Institute of Inland Southern California in Riverside will install a plaque in Alexander’s memory.

“It was such a tragedy, so what an honor to be able to celebrate his life,” said 49-year-old Steve Kwon, who drove up from Foothill Ranch with his friend to participate in the golf tournament. He had never heard about Alexander’s killing until recently.

“It’s outstanding that more people are knowing about Julian,” said Anthony Joseph, 65, of Las Vegas, a family friend who has attended the competition for five years. “It’s sad that stories like his are still happening.”

Bell spent most of the tournament readying the Morongo Golf Club banquet room for the reception. When it was time for her remarks, she looked around again and nodded.

“This is an interesting time,” she said, before asking for a moment of silence “to recognize the victims of 9/11, COVID and police violence.”

Then, Bell asked for another favor: Say her son’s name three times. The audience complied.

Julian Alexander.

Julian Alexander.

Julian Alexander.

Bell broke down in tears.

**

A couple of weeks later, I visited Bell at the well-kept Moreno Valley home she shares with her husband. Dozens of photos of Alexander covered her dining room table. Julian as a baby. As a toddler. Next to cardboard cutouts of Tom Hanks and other “Apollo 13” stars during a visit to Universal Studios Hollywood. With his wife of nine days, Renee.

“We were beginning to have grown-up talks,” said Bell, a retired educator for students with disabilities. “About fatherhood. About being a good husband. A good man. A good son.”

The 63-year-old has vivid memories of Alexander — his love of animals, his giving spirit, his perpetual curiosity. But she admits that what few memories she has of the years just after Alexander’s killing are spotty and painful.

Four generations of her family were able to watch Obama’s victory speech together only because that was the day of Alexander’s funeral. Bell remembered having to pull over on the 91 Freeway on trips back to Orange County to compose herself while she and her daughter-in-law pursued separate federal lawsuits against the Anaheim Police Department. (Anaheim settled both for $1.55 million in 2010.)

She wore a dog tag with her son’s photo until too many people asked about it. Bell attended church every Sunday, only to weep at the thought of her son looking down on his pained family from heaven.

“I didn’t know how to survive,” she said quietly.

Bell found solace through a network of Black women associated with Jack and Jill of America, a national organization for Black children. Many Inland Empire members were there the day of the golf tournament, checking in participants, arranging centerpieces, or selling $5 pins with Alexander’s face and the slogan “Justice for Julian Alexander.”

“We were all his aunties,” said Bernadette Pinchback, a retired manager for the San Bernardino Superintendent of Schools who sits on the scholarship fund’s board of directors. She and other Jack and Jill members were there at Alexander’s wedding reception. “He was a fine young man who lived a beautiful and clean life.”

“I’m usually pretty good one for dealing with deaths, but this one just got to us,” said NAACP Riverside President Regina Stell. “It was just unfathomable. To this day, it doesn’t make any logical sense.”

Pinchback, Stell and others helped Bell push forward with the scholarship fund — to offer financial assistance to high schoolers, yes, but also as a way to keep teaching young people about her son. Applicants are asked to research Alexander’s life and write an essay about how they might have relate to him. Bell and her committee pick about five winners every year.

“These kids don’t think [death by police] will happen to them,” Bell said. “We didn’t think it would happen to him. It happens.”

Outside of a few panels and speeches over the years, she didn’t involve herself much in the movement to highlight police killings of Black men and women.

“I’m not in that,” Bell admitted. “I’m not comfortable talking. I’m just not that well-spoken.”

But the renewed interest in Alexander’s case has inspired her to slowly open up.

“She’s become stronger — more assertive, more focused,” said Alfred Bell, Sheryl’s husband. “But Julian’s name in the national discussion doesn’t bring him back. It gets a little better, but it doesn’t go away.”

Last year, she attended a Black Lives Matter rally in Riverside, where thousands of people said Alexander’s name, an event she described as “cathartic.” More people are reaching out to learn about his life than ever before.

“It makes me feel good that he’s not forgotten,” Bell said. “We always wanted him remembered. It doesn’t diminish the pain, but the world deserves to know that he was killed. He was an innocent person who was killed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.