Nearly 29 years had passed when Trino Jimenez decided to write to the man who murdered his brother, prepared to never hear back.

The killing, in South Los Angeles, had been brutal. Melvin Carroll had struck Julio Jimenez repeatedly over the head with a bumper jack during a car theft. He walked away and then panicked, returning to slit Julio Jimenez’s throat with a broken bottle.

But Jimenez, a devout Christian, was ready to forgive.

“I can never forget him, but I am not consumed about an event that can never be undone,” he told Carroll in his February 2015 letter. “God loves you and even the crime of murder is a forgivable offense.”

Within a few weeks, he received a response, setting the stage for an almost unthinkable friendship. It challenges the notion that, for the most egregious cases, victims and those who have caused harm should always be kept apart.

A little-known California prison program facilitates dialogues between prisoners and victims. Some have turned into friendships.

The relationship would change each man, launching them on respective journeys of forgiveness and remorse — a journey Jimenez has largely taken without other members of his family.

They would ultimately meet through a little-known state program that brings prisoners together with survivors and families of victims and which advocates say has the potential to help far more people heal from trauma.

::

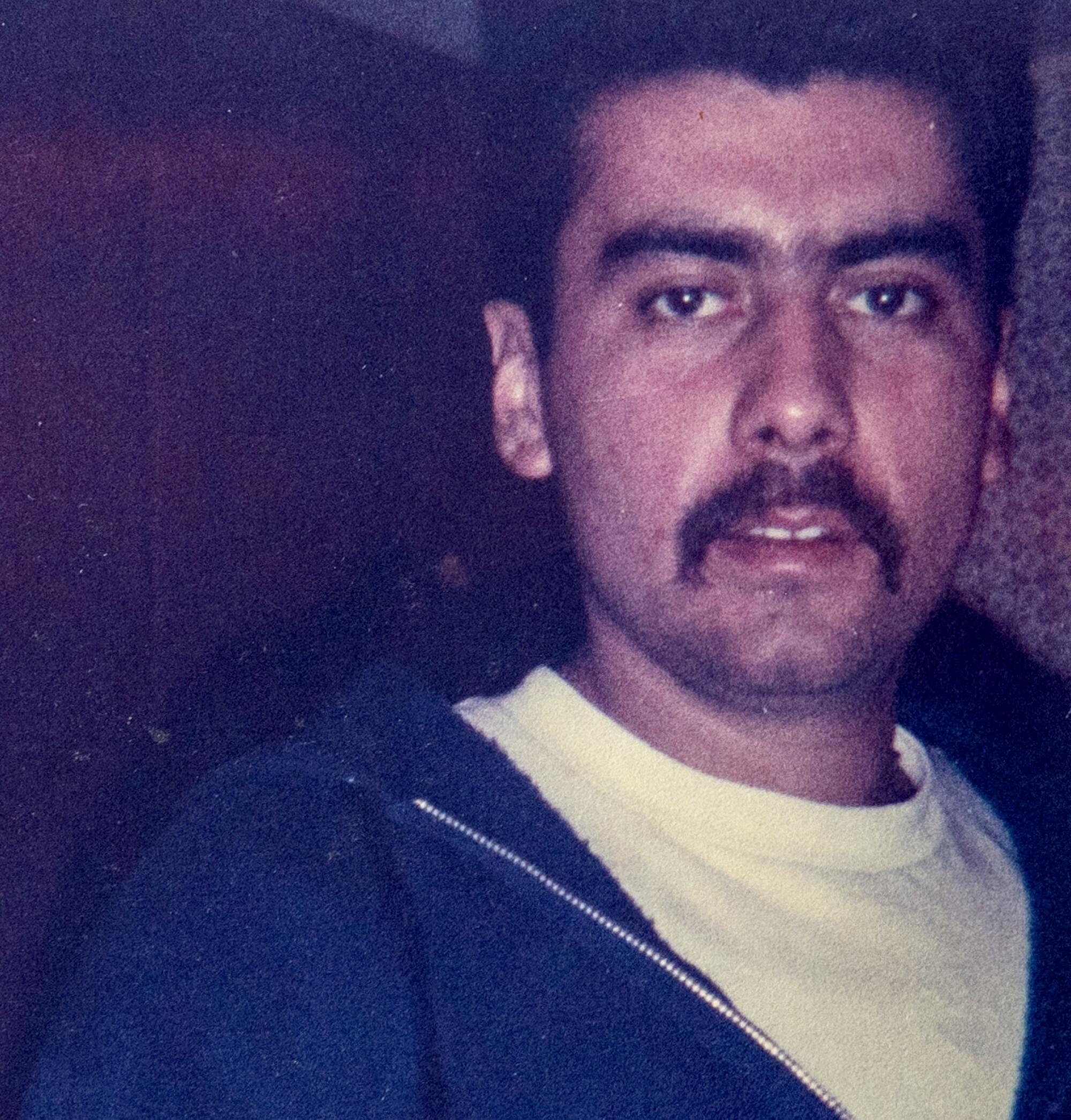

Julio Jimenez, the eldest of four brothers, grew up in a Mexican family in Huntington Park. By age 24, he was working in a South L.A. warehouse supporting a 4-year-old son and a baby boy.

He enjoyed fatherhood and life’s simple pleasures, like driving his prized blue Chevy Monte Carlo around town. But like some of his friends, he frequently used PCP, a drug known as angel dust. He’d buy PCP-dipped cigarettes from Carroll, a man close to his age who had spent the previous several years in prison for robbery and grand theft auto.

On Feb. 27, 1986, Carroll, along with two other men, decided to steal Julio Jimenez’s car. After the two men hot-wired the car and began driving away, Carroll told Julio Jimenez that it had been stolen. He invited him into his own car, pretending to help him find the Chevy.

They got out at South L.A.’s Slauson Park. Julio Jimenez grew suspicious and accused Carroll of being involved. Carroll denied it, then hit him when his back was turned, bashing his head 17 times.

His body was found by two people at 1:45 a.m. with a pocket turned inside out. Almost two years later, Carroll was sentenced to 26 years to life.

::

Trino Jimenez was 18 when his brother died, but much of that year is blacked out in his memory. He began to distrust Black people — Carroll is Black — and briefly turned to alcohol to numb the pain.

“I was very damaged,” he said. “I actually wanted to hold the entire Black race accountable for him.”

The death was too painful for the Jimenez family to talk about. Jimenez would go on to raise a son and two daughters, work for 30 years for a roofing manufacturer and travel overseas for missionary work.

But two encounters over the years with people convicted of heinous crimes made him reflect on forgiveness and one’s capacity to change. He met a cousin who had served time for murder and seemed to have transformed his life, and he later testified as a character witness for a murderer who had been part of his church’s bible study.

Jimenez eventually sought to contact Carroll. In 2014, a former prisoner he met through his church found Carroll’s prison identification number and told Jimenez he could request a transcript of Carroll’s parole hearing.

It was then that he learned that Carroll had taken a life in his early teens, when he was confronted by a woman inside a home he was burglarizing and hit her over the head with a glass jar.

Carroll spent about 18 months at a juvenile facility in Texas before moving to California, where his life continued to spiral downward as he was arrested for robberies.

Jimenez was troubled but began to see Carroll with “much deeper understanding and compassion.”

::

At a prison in Vacaville, Carroll recognized the last name on the letter and expected hate mail.

Instead, he could barely believe what it said.

“After this occurrence, I faced many struggles, my heart was filled with anger and not only an anger towards the people responsible, but towards an entire race,” Jimenez wrote. “God had to help me with my struggles, with my anger, eventually He carved out this anger from me.”

A friend told him Jimenez sounded sincere, so Carroll sent him a typed response. He was overwhelmed that Jimenez had strong faith in God despite losing his brother and told him that “through your letter God has restored me.”

He had come “to understand that I must take responsibility for every one’s life that I destroyed on 02/28/1986,” he wrote.

When Jimenez got the letter, he cried as if he had just lost his brother. He realized Carroll was not the only one who still needed healing.

In his next letter, he asked Carroll why he had killed his brother so violently. Did he owe him money? Do him wrong? Or was it just to rob him?

Carroll replied that Julio Jimenez “did nothing to deserve death,” but had been a victim of his “predator type life-style, and a criminal way of thinking.”

The exchanges continued steadily and grew more intimate. Jimenez sent Carroll a copy of his brother’s death certificate and disclosed that he, himself, was named after his grandfather who died in prison while serving a murder sentence. Carroll revealed he had been denied parole again.

Jimenez’s letters touched others. Carroll told him that they had almost created a Bible study circle in his building as inmates tried to understand the Scriptures that he sent, often on God’s forgiveness of sin.

As they corresponded, Carroll said in an interview, he began to truly feel the pain he had caused the Jimenez family. After so many years of hurting people, he said, “remorse wasn’t part of my lifestyle.”

“I started feeling it, and it hurt, it freaking hurt, because I never thought about remorse. Never. All I thought about was the time that I had to do,” he said.

::

California’s prison system began hosting meetings between victims and inmates in the 1990s. Victim-offender dialogues, as they are known, are a hallmark of restorative justice, an approach that emphasizes repairing harm through dialogue and accountability. It’s attentive to how prisoners have also often experienced trauma.

Over the last few decades, the practice has grown across the country, partly due to a public shift toward rehabilitation and alternatives to incarceration, according to Thalia González, a professor at Occidental College who has studied the dialogues nationwide.

In California, only survivors and next-of-kin of victims can initiate a dialogue by reaching out to the prison system’s Office of Victim and Survivor Rights and Services. If an inmate agrees and passes a screening, a trained facilitator separately prepares both parties. The process can take months, and the facilitator may work with the prisoner on taking accountability, as well as feelings of guilt and shame.

The meeting is not documented in the prisoner’s main file to ensure it has no impact on their status in the corrections system. Some victims participate in secret because their family may not approve.

“For people who are survivors, there might have been a trial or plea bargain but those don’t necessarily give you the truth,” said Rebecca Weiker, a dialogue facilitator.

“They might have questions only that person can answer. They might want to know if the person is sorry, if they understand the impact that happened. Just knowing that they understood the harm, they understood the impact, is incredibly powerful.”

“. . . remorse wasn’t part of my lifestyle. I started feeling it, and it hurt, it freaking hurt, because I never thought about remorse. Never. All I thought about was the time that I had to do.”

— Melvin Carroll, convicted of the 1986 murder of Julio Jimenez

But the dialogue program is not well-known or widely used. There have been only 58 first-time dialogues from 2011-21 and at least 192 requests since 2017, according to the prison system. (A few pairs have met multiple times.)

Mike Young, an assistant chief in the office of victim services, estimated only about 30% of requests end up in a dialogue, sometimes because the prison doesn’t think one side is ready. He said that they weren’t advertised heavily in recent years because of concerns about whether officials could support a large influx of requests. With the encouragement of Gov. Gavin Newsom, the prison system awarded grants in 2019 to several community groups with trained facilitators.

Young hopes that a new apology-letter program, where victims will have the opportunity to accept letters from prisoners, will also lead to more dialogues.

“The fact that a victim wants to go into prison to face their offender is extremely rare,” he said. “But the fact that it’s extremely rare should not mean they shouldn’t have that opportunity.”

::

The idea of meeting the Jimenez family was nerve-racking for Carroll.

Although two facilitators spent months preparing him for the dialogue, he paced the prison yard the night before, trying to collect his thoughts. The next morning, he thought to himself, “if nothing else, I was just going to go through that meeting.”

“I had come to terms with what I had did,” he said. “The next thing is when someone reaches out to you and tries to get closure, and you are the only one that can give it to him.”

The two facilitators, a support person for Jimenez, Carroll and Jimenez met in the visitor’s center of the Vacaville prison on a weekday in March 2017. A guard in the room sat out of hearing range.

Jimenez’s eyes locked on Carroll as he began to walk toward them. Carroll was shaking.

Before they started, Jimenez took Carroll’s hands in both of his. He prayed that the same hands that had picked up the bumper jack “would be the instrument of love now.”

He showed Carroll pictures of his family, including his brother’s children, to convey that his life had managed to move past the crime. He also brought a photograph of his brothers by Julio Jimenez’s grave.

Carroll was moved to tears.

“I didn’t understand it,” he said. “The man started sharing, and for me and the life that I lived, it was unusual.”

Carroll told Jimenez he thought the murder could be traced to an incident he witnessed as a child. A white law enforcement officer had slapped his grandmother after pulling her over, he said.

She had begged him to not tell his grandfather, so he kept it to himself. But from then on, Carroll said, he began to harbor hate for other races. Every time he was released from prison or jail, he “came out worse.”

“It wasn’t violence, it was extreme violence,” he said of killing Julio Jimenez. “None of it was necessary, but that’s what my frame of mind was.”

After six hours of talking, the two men embraced. Carroll was later smiling so hard that he was asked if he had been found suitable for parole.

“Being forgiven for the hurt you caused a family, that took so much weight off my shoulders, like I was soaring on my way back,” he said. “They said, ‘You got found suitable?’ I said, ‘Hey, I got something better than that.’”

::

In December 2019, Jimenez attended Carroll’s parole hearing at the Sierra Conservation Center prison in Tuolumne County.

He said that although he could not deny the pain Carroll had caused, Carroll had apologized not only in the first letter, but also in subsequent ones. Jimenez told commissioners his relationship with Carroll led him to become an advocate for restorative justice, work that included going back into prison to share their story with other inmates.

“I myself have been given a chance to — to further heal, and all of that started because Mr. Carroll said yes to me,” he said.

The commissioners granted Carroll parole, saying that Jimenez’s statement had helped them consider his ability to see the impact of his crime.

But grief is complicated. When Jimenez learned of Carroll’s release, he was hit with guilt. He thought about his two other brothers, who he sensed were not quite as ready to forgive and had opted to not attend Carroll’s parole hearings. He has not shown them his correspondence with Carroll.

“I asked myself if I was contributing to my brothers’ pain,” he said.

::

Today, Carroll, 61, works helping the homeless in Northern California and says he wants to “live my life, or what I have left, in peace.”

The two men have each other’s phone numbers and check in occasionally. They’re protective of each other, and their relationship is one where if Jimenez asks something of him, Carroll feels he should honor it.

“I owe that man everything,” he said. “He helped me get my freedom, and that was the most important thing to me at the time because I didn’t want to die in prison. How can you not admire someone like that?”

But Jimenez, 53, has been careful about how he’s spoken about Carroll to his family. In 2018, he decided it was time to “rope in” another family member and asked Carroll to write his mother a letter.

Thinking about his brother still quickly brings his mother, Maria Jimenez, to tears. Sitting in Trino Jimenez’s home, where she lives, she hugged a large photograph of Julio Jimenez as a child to her chest and could barely speak when asked about her son.

Between deep breaths, she recalled how the night Julio was killed she had stayed up waiting for him to return home. After a detective showed up the next morning, she had searched for her husband to tell him the news.

She said that she doesn’t hold malice against Carroll anymore and that God should bless him. While she described crying when she read the apology letter that Carroll sent her, she grew quiet when asked whether it had made a difference.

“It was well written,” she said. “But the pain is there.”

::

Jimenez works part time for a mortuary, and on a recent Friday, he set up heavy flower arrangements around a burial plot at the Resurrection Cemetery in Rosemead.

He then drove up a hill to Julio Jimenez’s grave, dusting off the marker and setting down three pink roses.

At the gravesite, he often reflects on how his brother’s memory has become stronger since he met Carroll. He’s even considered bringing Carroll there one day.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.