‘No justification’ for shooting by Long Beach school safety officer, experts say

The Long Beach school safety officer who opened fire Monday on a moving car filled with young people, critically wounding one of the occupants, may have violated policy, according to documents obtained by The Times and several law enforcement experts who reviewed videos of the shooting.

According to a use-of-force policy from Long Beach Unified’s school safety office, officers are not permitted to fire at a moving vehicle. Firearms may be discharged only when reasonably necessary and justified under the circumstances, such as self-defense and the protection of others, the policy states. The policy also bars shooting at fleeing suspects.

Chris Eftychiou, a spokesman for the Long Beach Unified School District, said the school district was “carefully reviewing multiple aspects” while cooperating with the Long Beach Police Department, which is working with the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office on an investigation into the shooting.

“We need to defer to the investigative agencies for questions about adherence to policies,” he said. Neither agency would comment on potential policy violations Thursday.

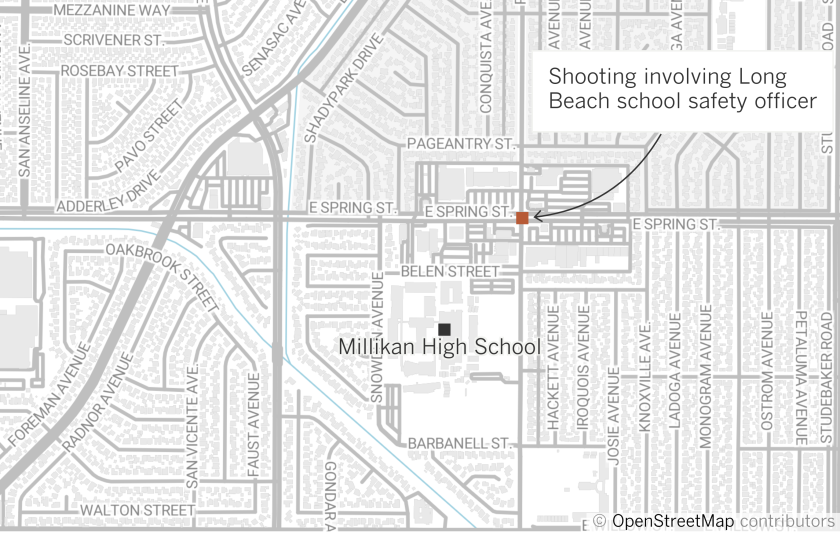

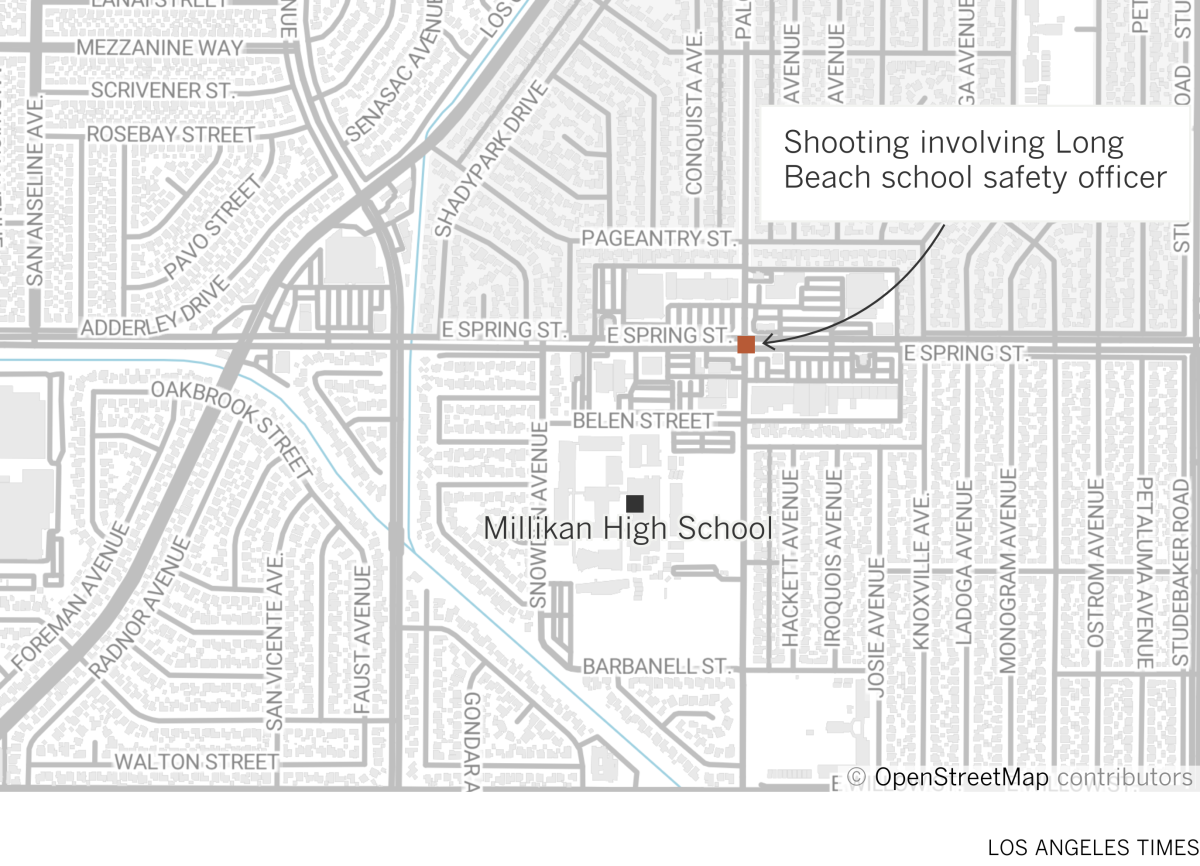

Officials with the Long Beach Police Department said the safety officer, who has not been identified, was driving about a block away from Millikan High School when he saw two teenagers fighting on the sidewalk about 3:15 p.m. and stopped to intervene.

One of the teens, later identified as Mona Rodriguez, jumped into the passenger’s seat of a gray sedan and tried to leave, and the safety officer opened fire, police said. Video posted to social media appears to show the officer firing at least two shots at the car as it moves past him.

No evidence has emerged that anyone involved in the fight was armed, and a friend of the driver said no one in the car that drove off attended Millikan High.

Authorities said Rodriguez, 18, was struck in the upper body. Her family said she was shot in the back of the head.

She remained in critical condition at Long Beach Medical Center on Thursday afternoon, hospital officials said. Her family said Wednesday that she was brain-dead and on life support.

Mona Rodriguez was on life support Wednesday, her family said. She is the mother of a 5-month-old boy.

The Times reached out to multiple law enforcement experts who reviewed the videos on social media and said, based on the current evidence, that the shooting appears unjustified.

Seth Stoughton, a former Florida police officer and a University of South Carolina law professor who studies shootings, said most law enforcement training today strongly discourages officers from firing at a moving vehicle, which is “highly unlikely to actually stop the car and risks making the situation worse.”

“Officers can use deadly force when they reasonably believe the subject presents an imminent threat of death or great bodily harm,” he said, noting that although the car was turning right while the officer was standing on the passenger’s side, “the threat was minimal and all he had to do to make it nonexistent was slide back slightly.”

By the time the officer began firing, he already was near the back of the car, Stoughton added.

“The car isn’t a threat, so there is no justification for the use of deadly force here.”

Rodriguez’s 20-year-old partner, Rafeul Chowdhury, said Wednesday that he was driving the car and that his 16-year-old brother, Shahriear Chowdhury, was in the back seat when shots were fired.

The officer had threatened to use pepper spray to break up the fight between Rodriguez and a 15-year-old girl, who was not identified, the elder Chowdhury said, but he did not indicate he was armed. No one in the car had a gun, he said.

“It was all for no reason,” Chowdhury said through tears. “The way he shot at us wasn’t right.”

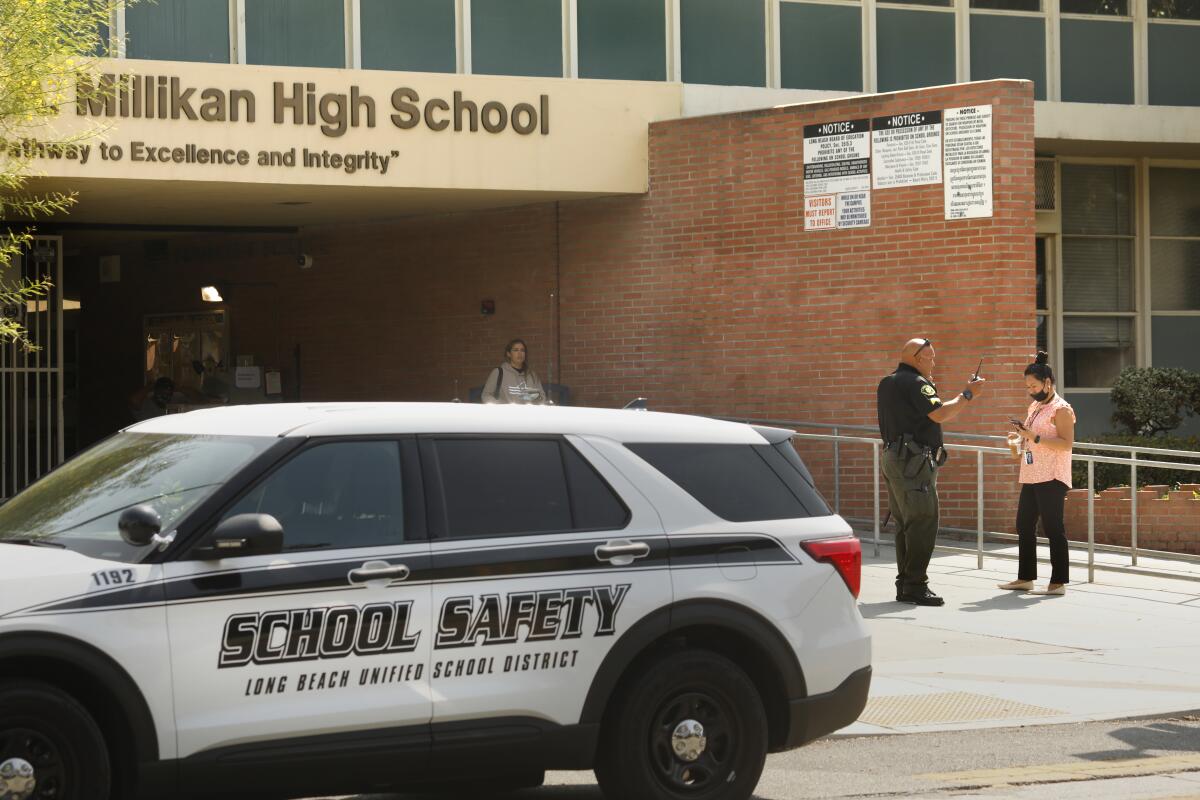

The Long Beach school district employs nine full-time and two part-time safety officers, as well as four supervisors, Eftychiou said.

The school district is a “separate government entity” from the Long Beach Police Department, the city said in a statement, and the officer involved in Monday’s shooting is not employed by the city.

District officers provide their own duty weapons, which are approved by their supervisor and selected from a list that is accepted by law enforcement agencies, Eftychiou said.

Monday’s incident is the first shooting involving a safety officer in the program’s 30-year existence, Eftychiou said.

A retired Long Beach Unified school safety officer, who asked to remain anonymous, said officers go through a police academy followed by a short probationary period, but their training is “not anywhere close” to what officers at the Long Beach Police Department and similar agencies receive.

School safety officers were told not to engage in issues off campus, he said. They can detain people but cannot make arrests beyond citizen’s arrests.

The retired officer, who said he spent more than a dozen years in the same position as the officer involved in Monday’s shooting, said he studied videos of the shooting from various angles and felt the officer was in the wrong — both for unholstering his weapon and for firing it.

“What that officer did was completely out of line of the protocol,” he said.

Retired Los Angeles Police Sgt. Cheryl Dorsey watched cellphone videos of the shooting and said it was “another example of a police officer using his gun to stop an alleged suspect.”

“There was no imminent threat to his life as the car sped away from him,” Dorsey said.

In a statement issued Thursday, the city of Long Beach called the shooting a “horrific incident” that has affected many in the community.

Mayor Robert Garcia said on Twitter that the city was “heartbroken” over the events.

Mona Rodriguez was on life support Wednesday, her family said. She is the mother of a 5-month-old boy.

In a letter to California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, Luis Carrillo, an attorney for Rodriguez’s family, said that the young woman did not pose an imminent threat to the officer and that the use of force was unjustified.

The lawyer suggested the officer’s actions “meet the threshold for criminal charges,” including murder or manslaughter if she dies.

Reached by phone Thursday, Carrillo said justice was a top priority.

“The focus right now is to make as much noise as possible to get him arrested,” he said of the officer. “That’s No. 1. No. 3 will be the civil process, because No. 2 will be the healing and the funeral.”

School district officials confirmed that the officer has been placed on paid administrative leave, as is protocol after a shooting. No students were injured in the shooting, they said.

The officer fired at a car about a block from campus as it sped away, striking a young woman inside, authorities said.

At a vigil Wednesday night, Rodriguez’s brother Oscar Rodriguez said he did not want her taken off life support, although she has been described by other family members as brain-dead.

A GoFundMe page has been set up to assist with legal and funeral expenses, as well as child care for Rodriguez and Chowdhury’s 5-month-old son, Isael.

Charles “Sid” Heal, a retired L.A. County sheriff’s commander who has testified in hundreds of use-of-force cases, said that unless a firearm was in the vehicle, an officer who fired a weapon may face criminal charges.

“The car clearly was not a weapon, as it was moving away from him when he fired,” he said.

Heal said the shooting raises larger questions about the school officer’s training and why he would consider it reasonable to shoot in that situation.

Data collected by the Washington Post’s police shootings database show 1,061 people were fatally shot while fleeing in a vehicle since the beginning of 2015.

The Supreme Court has ruled that officers can use deadly force against a fleeing individual only when that person presents a serious danger to the officer or others. Departments nationwide have in the last 15 years adopted policies that state officers cannot shoot at a vehicle unless there is a threat of a suspect using deadly force other than the vehicle.

In 2016, the Police Executive Research Forum set out guiding principles in an effort to reduce police shootings, including discouraging firing at moving vehicles.

And this year, the Los Angeles County Board of Education approved a plan to cut a third of its school police officers, with activists arguing that Black and Latino children disproportionately experienced harsh tactics such as pepper-spraying. Other jurisdictions are considering similar measures.

Heal said most police agencies in the last few decades have stopped officers from shooting at vehicles unless there are extreme circumstances.

“Unless someone inside the car was posing a lethal threat, I don’t see how it can be justified,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.