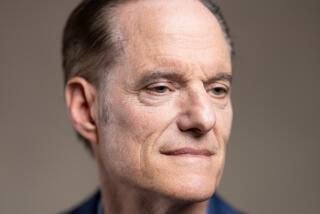

Larry Elder’s private charity was a bust, and questions swirl over where the money went

Larry Elder, the GOP front-runner in California’s recall election to replace Gov. Gavin Newsom, has long trumpeted a libertarian view on the “welfare state” and its excesses, arguing private charity is a better solution than government programs.

But the conservative radio host’s own nonprofit raised little cash and made no grants in the nearly two decades it was active, a Times review of its annual tax filings show.

From 1998 through 2014, Larry Elder Charities Inc. raised about $20,000, according to public tax filings. It spent no money on any services, other than accounting, legal and filing fees to keep the organization in good standing. The organization has been suspended by the state since 2015 for failing to pay a filing fee, according to a spokesperson with the Franchise Tax Board.

The IRS automatically revoked the charity’s tax-exempt status in 2018, three years after it stopped filing the required paperwork, according to IRS records.

Questions about Elder’s aborted charity have emerged as he leads in fundraising and polls to succeed the Democrat Newsom if he is recalled.

The nonprofit’s last tax filing showed just under $15,000 in remaining funds, and charity experts said Elder is ethically obliged to disclose what happened to the money. The organization’s articles of incorporation promised to distribute the funds to other charities and nonprofits should it shut down.

“$15,000 is not a lot of money in the nonprofit sector on the whole, but that’s a lot of money to people who have unmet needs,” said Laurie Styron, executive director of CharityWatch, a national organization that monitors and rates charities for the public.

A spokeswoman said Elder wasn’t available for an interview.

His campaign didn’t answer questions submitted by The Times about what happened with the charity or its remaining funds or provide an accounting of how much Elder has given to charitable causes.

A spokeswoman with the campaign said Elder “has given to a number of different charities over the years, including Food for the Poor, Angel Tree Prison Fellowship, A Place Called Home, and Brotherhood Organization of a New Destiny.”

“Larry Elder has been a strong supporter of charitable giving and the many organizations that do it well,” communications director Ying Ma wrote in an email.

Ma criticized The Times for spending “significant resources on a small organization with a small amount of money that shuttered its doors many years ago,” and said the newspaper should focus on Newsom’s “cronyism and corruption.”

Women approve of Newsom’s handling of COVID but are less enthusiastic about voting.

From natural disasters to Medicaid, Elder has long scorned government as a feeble solution that harms more than it helps. He’s argued that private groups, individuals and corporations are better-suited to assist poor people and provide disaster relief.

“Life is not fair. But it is unfair to assume that an America without a government-provided safety net would turn its backs on the less fortunate,” Elder wrote in a 2017 column criticizing the Affordable Care Act. “Charity is in America’s DNA.”

His own nonprofit said in its mission statement that it would provide “(non-governmental solutions) to inner city problems.”

It’s unclear how much work Elder and the group’s board of directors put into making the organization successful, and there’s scant mention of it in public. In 2003, an announcement in The Times mentioned a comedy stand-up show at Pasadena’s Ice House Comedy Club to raise money for the charity.

However, the charity has been used in short biographies about Elder that appear occasionally and tout his philanthropic efforts, including the website for the Hollywood Walk of Fame, where Elder has a star embedded in his honor.

“Elder has established the Larry Elder Charities, a non-profit organization that contributes to groups and individuals offering non-government, self-help solutions to problems of poverty, crime, poor parenting, dependency, and education,” the bio reads.

A federal judge in Los Angeles on Friday dismissed a lawsuit that claimed the California recall election violates the constitutional principle of one person, one vote.

One person listed as a board member on federal tax records who did not want to be named for fear of retaliation said they didn’t recall even being on the board.

Another former board member, Jennifer Hardaway, said she recalled the charity but said it didn’t seem a priority in Elder’s office at his Hollywood Hills home. Hardaway also worked for Elder as an assistant for several years.

“There wasn’t anyone actively working on it that I recall,” Hardaway said. “That doesn’t mean it wasn’t being worked on, I just don’t remember anything.”

Elder has argued for abolishing the IRS and dismantling a bevy of other federal agencies.

He’s criticized food stamps as a government giveaway to people who abuse the funds and spend the money at places such as strip clubs, suggesting in a 2013 column that EBT cards be replaced with private generosity.

“Is government welfare — as opposed non-government charity — the best way to help the needy and to encourage self-sufficiency?” Elder wrote.

What about Medicaid, the government program that helps poor people defray medical costs?

“What about private charity instead of Medicaid?” Elder wrote in a 2009 column that also proposed eventually privatizing Social Security and Medicare.

He’s also discounted the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which provides relief and rescue operations after natural disasters.

“Why the reluctance to rely on private charity?” Elder wrote in 2007, suggesting that companies like Home Depot and Walmart had done a better job than government in supplying the needs of people devastated by Hurricane Katrina two years before.

Elder argued in 2009 against requiring insurance companies to cover people with preexisting conditions: “What’s wrong with charity-people helping people?”

As he was writing those words, his own charity was languishing. Its highest fundraising year was in 2003, when it raised a total of $7,736.

Many nonprofit experts and local nonprofit leaders say Elder failed to understand the massive hurdles charities would face in raising enough money to supplant government services.

“Larry, you disproved your theory,” said Noreen McClendon, executive director of Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles, which helps provide affordable housing and other services to low-income residents.

Even the nation’s largest nonprofits lack sufficient resources to fully fund public services such as education and disaster relief, said Megan Francis, an associate professor of political science at the University of Washington.

“It pales in comparison to the amount of money that local, state and the national government provide in terms of necessary social services that all Americans need,” she said. “It is important that public and private charities have a role in our society and they often have a role working hand in hand with government, but they cannot replace government.”

Francis noted that the public often is impressed with “reformer” candidates who perpetuate the idea that government is too big and needs better controls. However, there’s no real mechanism to hold private charities accountable, she said.

“The good thing with having so many of the social services provided by government and not by private charities is that you can actually hold government accountable,” she said.

Jim Ferris, the director of USC’s Center on Philanthropy and Public Policy, said nonprofits are often formed because there’s an unmet community need — either because of a failure in government or in private industry to address it. Nonprofits filling gaps for government can be a solution to some societal problems. But often it’s more of a “value-driven idea,” Ferris said.

“It’s a model that people resonate with,” he said.

Many nonprofit leaders agreed with Elder’s contention that private welfare organizations tend to be nimbler in addressing needs and avoiding the maze of bureaucracy and red tape that can hamper government action.

But private fundraising is extremely difficult, often subject to the whims of wealthy donors and dependent on extensive relationship building and trust, a heavy lift for any organization, experts said.

If anyone should have been able to start a successful, conservative-oriented charity, it should have been Elder, whose outspoken viewpoints have struck a chord within Republican circles across the country, McClendon said.

“Why weren‘t they donating to this guy? He’s the perfect poster boy: He’s Black and he doesn’t believe in the safety net. He had national recognition,” McClendon said.

Times librarian Cary Schneider contributed to this report

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.