How a Black prosecutor called out racism in the D.A.’s office

The headlines read as though they were written by protesters who routinely demonstrated outside the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

Why I Don’t Trust Prosecutors.

When Police And Prosecutors Are Partners in Crime.

When Innocence Is Inconvenient.

Unsparingly criticizing the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office, the accompanying essays accused the agency of a smorgasbord of malfeasance: racial discrimination, failing to protect employees from sexual harassment and failing to hold police accountable for misconduct.

Blunt and profane, the sentences quaked with anger at an institution the author viewed as fundamentally broken.

Though each post echoed criticisms that protesters lobbed last year at then-Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey, these calls for change came from inside the office.

The author was a prosecutor. His pen name: Spooky Brown Esq.

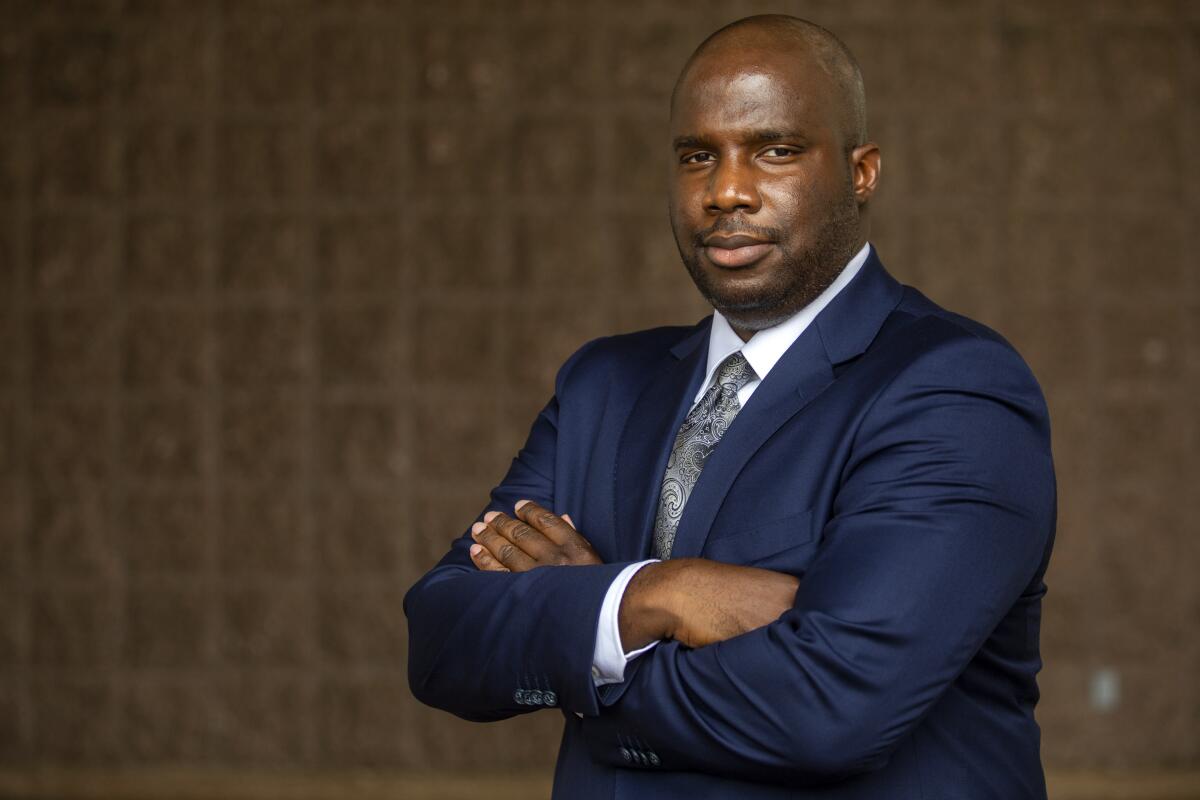

The man behind the alias, Adewale Oduye, had been a prosecutor since 2008. Oduye said his typing fingers were fueled by the culture of an office that has not charged a Los Angeles police officer in an on-duty shooting in two decades, one where he said colleagues openly mocked Black Lives Matter protesters, even when injured by police.

For years, Oduye had tried to handle the matters internally by writing memos to his bosses, including Lacey, or filing grievances against supervisors he considered racist, according to district attorney’s office documents.

When that didn’t work, he used the only weapon he thought he had left: his voice. In a dozen essays published on Medium under Spooky Brown’s byline, he accused supervisors of refusing to confront law enforcement misconduct or pursuing cases against defendants he believed were obviously innocent.

Oduye’s posts started to garner attention for intimately portraying the inner workings of the district attorney’s office, re-creating disturbing conversations among prosecutors and painting Spooky as a hard-charging attorney seeking justice in the face of colleagues interested only in convictions.

The posts marked a rare instance of a prosecutor publicly criticizing the office and came as most of Oduye’s colleagues supported Lacey as she faced an election challenge from former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who ousted her in November.

Some prosecutors dismissed the posts as rantings of a disgruntled employee. Others suspected a defense attorney or activist was trying to undermine Lacey. But Oduye said his actions had less to do with his politics than his patience, which ran out last summer when he watched George Floyd beg for his life beneath a Minneapolis police officer’s knee.

“What I wanted to do was to take agency and tell the story,” he said. “I was waiting for someone to save me, but I realized … no one else is going to do it.”

::

“As a line prosecutor, I’m required to follow the decisions that my supervisors make about people who are charged with crimes. Most of the time, my supervisors have been white, and the people charged have been Black and Brown. While some of those decisions have been right, too many of them have been wrong — dead wrong. I’m going to talk about some of the wrong ones.”

The paragraph from the first Spooky Brown post underpins both Oduye’s entrance and exit from the district attorney’s office. Oduye, the middle child of Nigerian immigrants, said the path that led to him to the legal field started in his family’s Brooklyn living room, where he watched Johnnie Cochran command the courtroom during the O.J. Simpson trial.

The sight of a Black prosecutor-turned-star defense attorney putting issues of racism in policing on trial alongside Simpson inspired Oduye to pursue a legal career. After earning his law degree from Northwestern University and a brief stint at a private practice in Chicago, Oduye moved to Los Angeles.

Texas’ Brooks County and the Rio Grande Valley to the south have been popular smuggling routes for decades. Six months into 2021, deaths in the county had already reached 55, up from a total of 34 last year.

He applied to both the public defender’s and district attorney’s offices, but chose the latter in the hopes of being an agent of change.

“A friend of mine told me being a prosecutor, especially as an African American male, is good because there’s not very many, and you could do a lot of good in the world,” he said.

It wouldn’t be long until he had that chance. Less than two years on the job, he was handed a case that would inspire Spooky Brown’s first post.

Though Spooky Brown gave officials and defendants pseudonyms to help mask his real identity, The Times corroborated some of his accusations through court records and interviews.

The man Spooky Brown called “Byron” was Erik Taylor. Records show that in December 2009, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies searched his apartment in South L.A. after pulling him over for a traffic violation. Taylor was on parole, so the deputies didn’t need a warrant to enter the apartment.

Deputies Victor Lemus and Joaquin Rincon said they found a shoe box containing a gun, marijuana and bullets beneath the couch, according to court records.

Oduye said the case was presented to him as a gift for a young prosecutor.

“Someone had told me it was a dead-bang case. A slam dunk. It’s no problem. You don’t have to think to do this case,” Oduye said in an interview. “But I’m not that type of dude. I’m gonna look at it and do my own investigation because that’s what a good D.A. does.”

Taylor faced up to 10 years in prison. Immediately Oduye had concerns. The officers’ stories were practically identical.

“That usually means witnesses improperly colluded,” Spooky Brown wrote.

Taylor’s defense attorney produced photos showing the couch sat flush against the floor, leaving no room for a shoe box. Oduye said that he questioned the deputies and that they insisted an 8-inch gap separated couch and floor.

The Times reviewed video evidence that showed the deputies filmed every part of the search — except when the gun and drugs were allegedly recovered.

Proposition 187 propelled some California Latinos into civic life and Democratic politics, even Congress. After Trump, could it happen again?

Oduye approached his supervisor, assuming the evidence would lead to a dismissal of the charges, maybe even an investigation of the deputies’ conduct. Instead, Oduye said, he was ordered to offer Taylor a plea deal. The deputies were a problem for the Sheriff’s Department.

“And that’s when my soul died,” Oduye said.

But Oduye held his ground. According to an internal report reviewed by The Times, the case was dismissed in 2010 “because of conflicting officer statements.” In the report, Oduye noted Rincon changed his story about where the items were found after being confronted with the pictures.

Greg Risling, a spokesman for the district attorney’s office, said that when Rincon was questioned about inconsistent statements, he “clarified that he found the gun, bullets and drugs on a shoe box top when he lifted up the couch.”

“There was no evidence that the deputy lied,” Risling said, adding that the office first learned of the alleged misconduct through the Spooky Brown post.

The internal report, however, notes that Lemus and Rincon held true to their story about the shoe box when Oduye first questioned them; Rincon mentioned a “shoe box top” only after Oduye confronted him with the photos.

“When asked the reason he did not explain this previously, [Rincon] said nothing,” the report read.

The Sheriff’s Department did not respond to questions about Taylor’s arrest. Attempts to contact Rincon, Lemus and Taylor were unsuccessful.

It is unclear whether Lemus or Rincon ever faced consequences for their shifting stories. The district attorney’s office emailed Spooky Brown seeking information about the case last year, but Oduye told The Times he’d told his supervisor everything he knew a decade earlier.

::

An Afghan tradition was all but stamped out by religious extremists who — hearing sin instead of song — outlawed music and threatened with death its practitioners.

The Taylor case was the first in a pattern Oduye saw develop over time. Oduye celebrated Lacey’s election in 2012, hoping the first Black woman to serve as Los Angeles County’s top prosecutor would aggressively pursue police misconduct. His faith was not rewarded.

His frustrations grew as Lacey declined to prosecute an LAPD officer in the killing of an unarmed homeless man in Venice Beach and offered what Oduye considered a sweetheart deal to a sheriff’s deputy accused of raping prisoners. When he saw the video of Floyd’s murder, that frustration took a toll on his health.

If there was ever a police shooting that would bring criminal charges against a law enforcement officer in Los Angeles, the killing of Brendon Glenn near the Venice boardwalk looked like it could be the one.

Severe neck pain sent him to an emergency room, where Oduye says he was diagnosed with stress-inducted meningitis. In the weeks after his discharge, Oduye found an outlet for the anger he had bottled up for 12 years.

“I knew I had to write something because generally D.A.s and Black D.A.s are fearful of saying anything, because they don’t want to piss off the powers that be,” he said. “And I felt like someone needed to say something about the way D.A.’s offices are run, from a Black perspective.”

Oduye handled alarming cases beyond those he chronicled as Spooky Brown. But if you ask, the stories come spilling out, like the one about Salvador Martinez, who Oduye says nearly spent his life in prison because of a feud between Oduye and his boss.

Martinez, a twice-convicted felon, had been charged in a 2016 road rage incident in which no one was injured, records show. On the eve of jury deliberations, Oduye offered Martinez a plea deal: 17 years in prison instead of life. But Oduye said his supervisor, head deputy Thomas Higgins, later claimed he never gave Oduye permission to offer the deal and ordered him to revoke it.

The two had not been getting along, and Oduye said the move was part of a pattern of behavior Higgins had undertaken to harm his career. Oduye filed a grievance against Higgins alleging racial discrimination and also created detailed memos about the Martinez case.

Higgins became the subject of an internal investigation, according to Martinez’s public defender and a colleague of Oduye’s, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal.

After a yearlong review, Higgins was replaced by a new supervisor and Martinez was allowed to accept the 17-year offer. Higgins resigned in 2019 and denied wrongdoing in comments made to the Los Angeles Daily News that year. He did not respond to emails or calls seeking comment for this story.

Risling declined to comment on Higgins but noted the office has a general policy requiring line prosecutors to seek approval from supervisors before offering a plea deal.

Redondo Beach addressed its homeless problem with a court diversion program that provides services instead of custody. When the pandemic brought it to a halt, the city came up with workaround. Now homeless court is held outdoors, in a police station parking lot.

“The outcome was far from perfect, but I knew that seeking true justice was almost impossible because it was buried under … politics, rampant bullying, and extreme racism. Therefore, success for me was about working within this broken system to achieve small victories.”

The “Spooky Brown” moniker came from “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” a 1969 spy novel about the CIA’s token hiring of its first Black officer. The protagonist goes on to use the agency’s teachings to become a revolutionary, fighting to aid Black communities throughout the U.S.

The cloak-and-dagger motif seemed appropriate for Oduye, who playfully describes himself as paranoid. Ahead of one interview for this article, he put down a false name on a diner’s waiting list after noticing LAPD cruisers parked nearby. Oduye said he logged on as Spooky Brown only from a private computer or on a burner phone. If Oduye was at work, Spooky didn’t type, tweet or text.

Spooky’s and Oduye’s voices are strikingly similar, just operating at different decibel levels. Oduye uses four-letter words more sparingly in person, but the self-righteousness and confidence that drip from the blog posts are present whether he’s speaking or typing.

It was unclear how hard, if at all, the district attorney’s office tried to identify Spooky Brown. Lacey and Risling declined to comment.

But among prosecutors, frustrations with the whistleblower were evident. Oduye said he often heard colleagues complaining about Spooky Brown at work.

The Times contacted several prosecutors who quickly made critical comments about Oduye. Though none would allow their names to be used, several derided him as a weak prosecutor or unprofessional, pointing to an incident in which he gave Lacey a rose dipped in gold shortly after receiving a promotion, a present expensive enough she had to disclose it under campaign finance laws.

Los Angeles County Dist. Atty.

In a recent interview, Gascón noted that Oduye felt he had to conceal his identity to critique the office for fear of reprisals, as many prosecutors now openly criticize Gascón’s policies. He said he hoped Oduye’s writings were a “wake-up call” for the office.

“From my end, it was a confirmation that there’s substantial cultural problems in the office that continue to this day,” Gascón said.

George Gascón ordered a number of major changes to the Los Angeles County D.A.’s office when he took office last week, but some of his directives are meeting resistance from judges and prosecutors.

::

Oduye said he revealed his alter ego only to his family and two close friends, both public defenders, but some colleagues began to have suspicions.

Joseph Iniguez, a prosecutor who now serves as part of Gascón’s executive team and also briefly mounted a campaign against Lacey, started to match up details in some of Spooky’s posts to conversations he had with Oduye.

Iniguez never asked Oduye whether he was Spooky Brown but found himself relating to the posts.

“I just felt like my voice wasn’t valued,” Iniguez said. “That’s another thing that Adewale and I at some point discussed, is that you’re going to be marginalized.... It’s something that we’re trying to change, but it’s so entrenched.”

Iniguez pointed to a training presentation given in the office last year that contained several images of what Iniguez considered to be offensive stereotypes of Latino and Black defendants — including a woman pushing a stroller with a baby named “Malo,” Spanish for “bad.” It was a sign of the office’s problematic treatment of employees of color, he said.

“It was a non-person of color mocking Latinos and an African American guy, and I thought the hell with it,” Iniguez said. “This is 2020 and they’re giving us a training with these images?”

Even with Spooky Brown as an outlet, Oduye’s frustration kept building, and days before Gascón defeated Lacey, Oduye outed himself and quit. In part, he wanted to quash murmurs that the Spooky Brown was actually a defense attorney. In part, Oduye said, he was just exhausted.

“The ability to do good work is being suffocated … and there comes a time when you’ve had enough. I can’t do no more, at this point in time,” he said.

Oduye is now taking part in a fellowship focused on opening a school where he hopes to use positive reinforcement — or in terms the progressive ex-prosecutor would probably prefer, “restorative” practices — to help at-risk youths achieve academic success.

In his final post, Oduye wrote under his own name and said he hoped he wouldn’t be the last prosecutor to speak out about injustice inside an office whose mission should be seeking the opposite.

“This office has made it a point to make employees feel powerless when they speak out. I must admit, there’ve been times in which I’ve felt absolutely powerless and inept. However, by coming out and telling these stories, I’ve realized that everyone has a voice, and everyone has power.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.