BOOM.

That’s what pops into my mind when I think about July 4 — mostly because illegal fireworks light up my Santa Ana neighborhood with such brilliance that they make the ones at Disneyland seem as spectacular as a fading flashlight.

This year, another type of explosion is preoccupying me — not the grand orations of our Founding Fathers but Frederick Douglass’ 1852 jeremiad, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

His answers weren’t pretty. To a group of white people, he deemed the holiday a “sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless.”

Yet Douglass, a former slave, ended his speech on a surprising note: guarded hope.

“While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age,” he concluded.

This lesser-known section came to mind after The Times interviewed 10 Southern Californians about what the Fourth of July means to them, in the wake of the hell year that was 2020.

A taco truck owner feels free because he became an American citizen. An activist dwells on who is not free: Black and brown Americans. A doctor mourns the lives lost from COVID-19. A single mom who was just laid off looks forward to a few days of relaxation. A homeless man feels that people have become insecure and unreachable.

All appreciate the freedom they have in this country but understand its tenuousness as the pandemic continues and Americans strive for the racial justice that still eludes them a century and a half after Douglass’ speech.

Michelle Reyes, a 37-year-old special education instructor and deejay who lives in Santa Ana, has always loved the holiday because of the annual party in her family’s backyard. It is a simple affair: carne asada, drinks and a front-row seat to the barrio fireworks.

This time around, the feelings are “complex.” COVID-19 ripped through Santa Ana, even as Reyes found professional success — mentoring girls at music camp, earning another professional degree — during the pandemic.

“All of my dreams are coming true, but my city suffered tremendously,” she said. “I can be liberated and also exist in a way that makes me feel not free.”

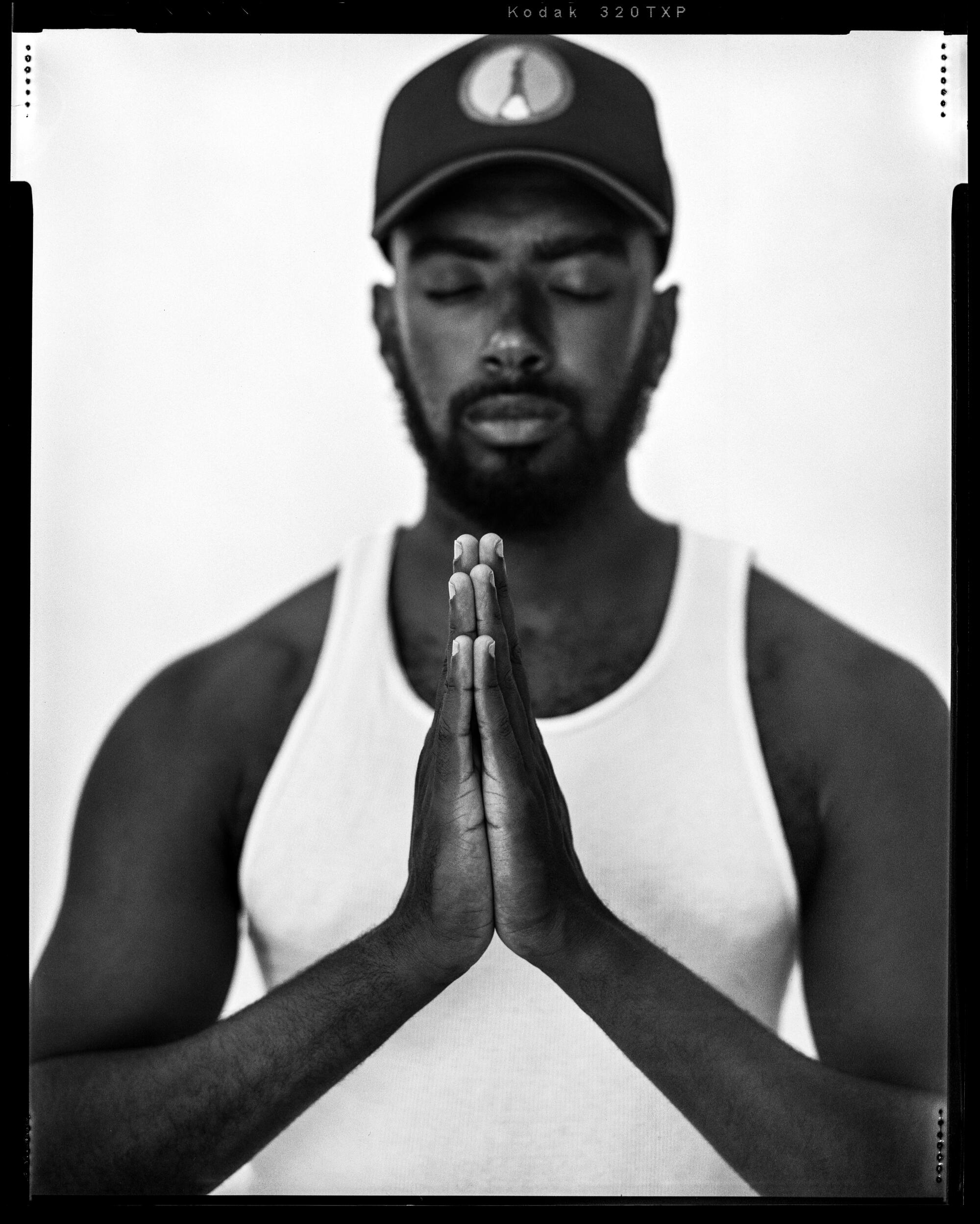

Etienne Maurice marched in Black Lives Matter protests last summer, founded WalkGood LA, a non-profit which provides spiritual healing through yoga in the park. Of Caribbean and African descent, the 29-year-old remembers celebrating the independence days of his parents’ home countries more than July 4.

“We found it much more important to amplify the voices of different cultures, the independence of other cultures and the melting pot of America” than something associated with “freedom from the British,” he said.

He remains skeptical of July 4.

“The opportunities and resources are still limited when it comes to Black and brown folks in America,” he said. “And to be honest, that isn’t independent and we have still yet to obtain that independence. Now, am I hopeful? Yes, but we have so much more to go.”

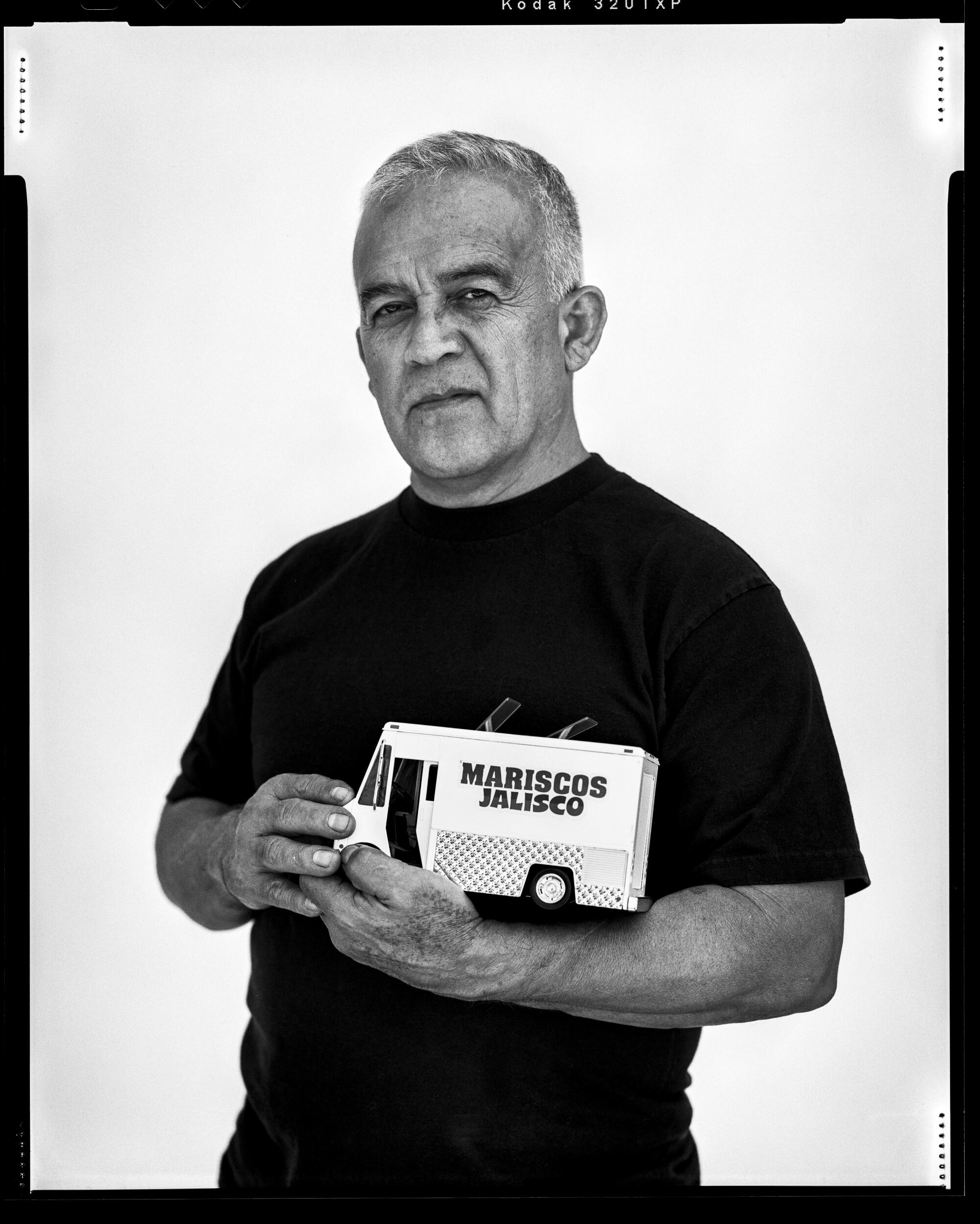

Raul Ortega, who runs Mariscos Jalisco in Boyle Heights, fully embraces the Fourth. Only on holidays does his famed taco truck close two hours early, so he and his workers can spend time with family.

This year, the day will be particularly special for Ortega — it’ll be his first as an American citizen.

“It gives me more and more freedom, more opportunities here,” he said. “I still have my Mexican feelings, but other cultures don’t have the privileges that we have here. And it’s an honor to be a U.S. citizen.”

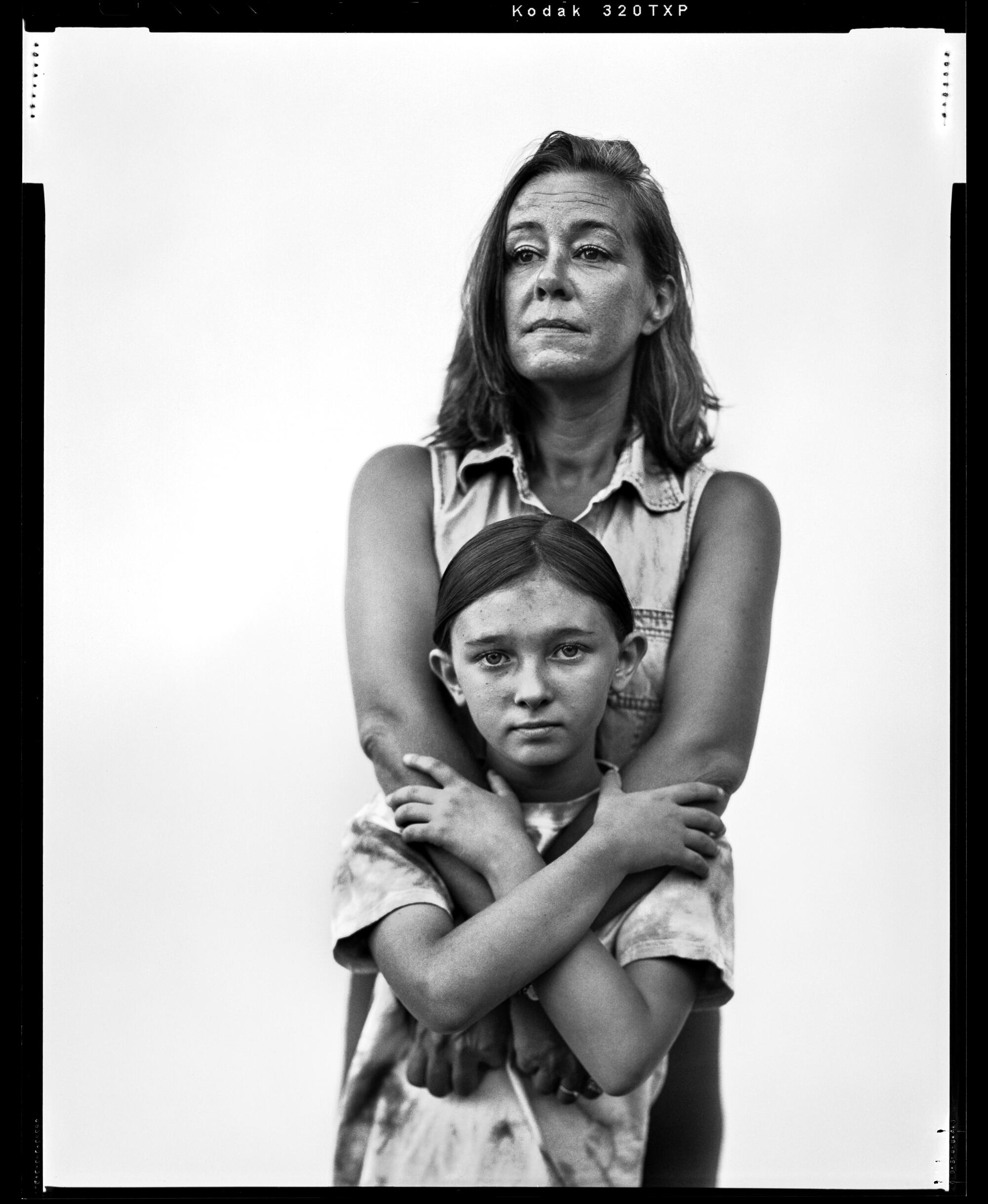

Loud, festive parties are on the mind of 44-year-old Jamie Eagen, a single mom laid off during the pandemic from her job as a law office manager.

She has fond memories of July 4 growing up in Westchester. Her neighborhood always held a block party where “we were free to be kids and have fun with our parents and neighbors.”

This year, she and other family members will pool money together to rent a houseboat on Lake Powell.

She’s still trying to find a job after being laid off for the first time in her life, but she chooses to focus on the positive lessons.

“It was like once I walked through that and had that happen, and it’s almost like having your worst nightmare come true and realizing that you’re OK,” Eagen said. “It gives you a sense of freedom that you would not think it would give you.”

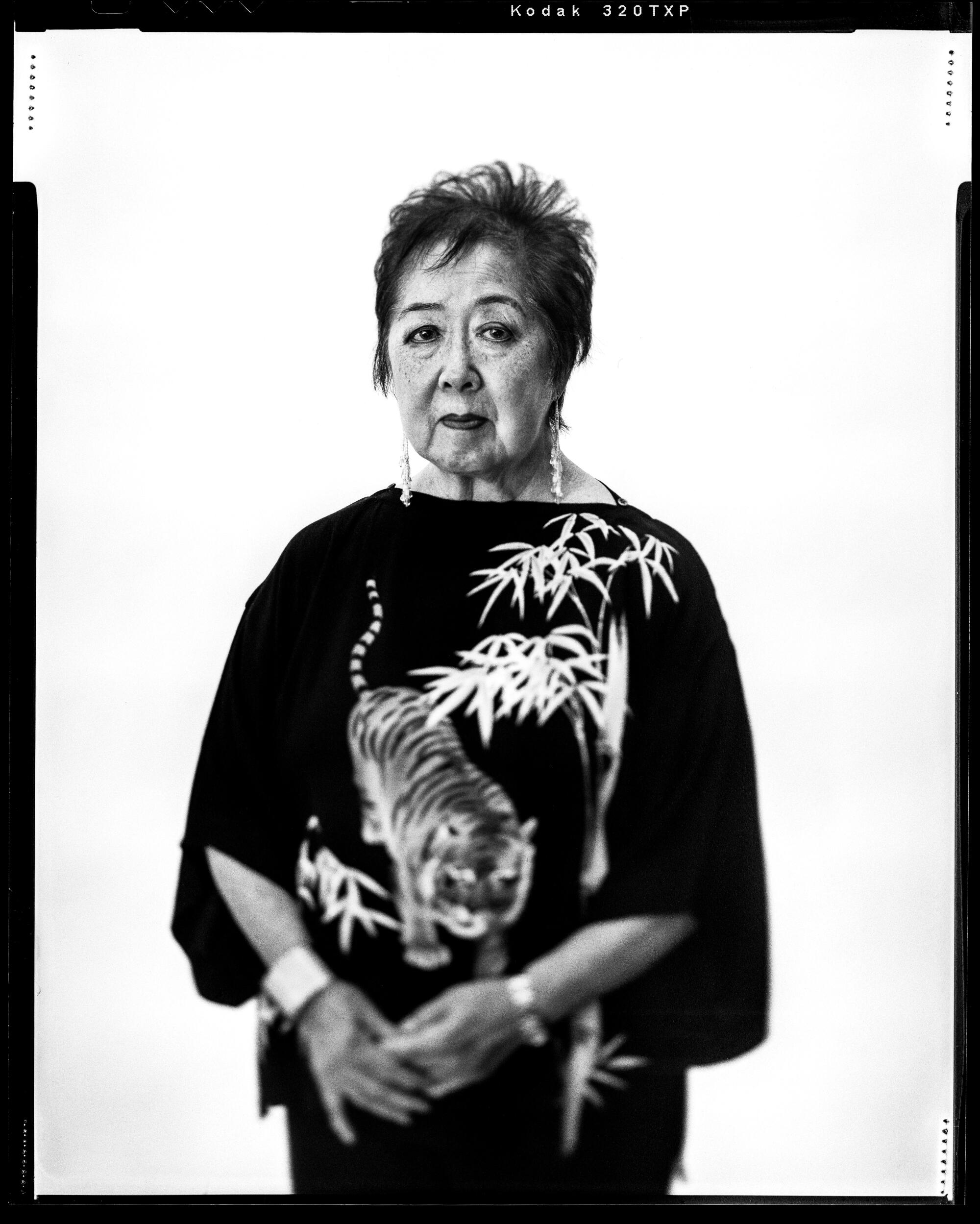

For Miya Iwataki of South Pasadena, July 4 means ruminating on the Declaration of Independence and its various promises, specifically the one guaranteeing Americans the “pursuit of happiness.”

A rash of police violence over the last decade has made her question the validity of that iconic line.

“Each killing and each acquittal of officers involved raised questions about justice and freedom,” said Iwataki, a veteran activist.

But after a year where many sheltered in place and reflected, Iwataki says she feels optimistic the U.S. will someday let everyone pursue their happiness freely — thanks to young activists like her niece, Ana.

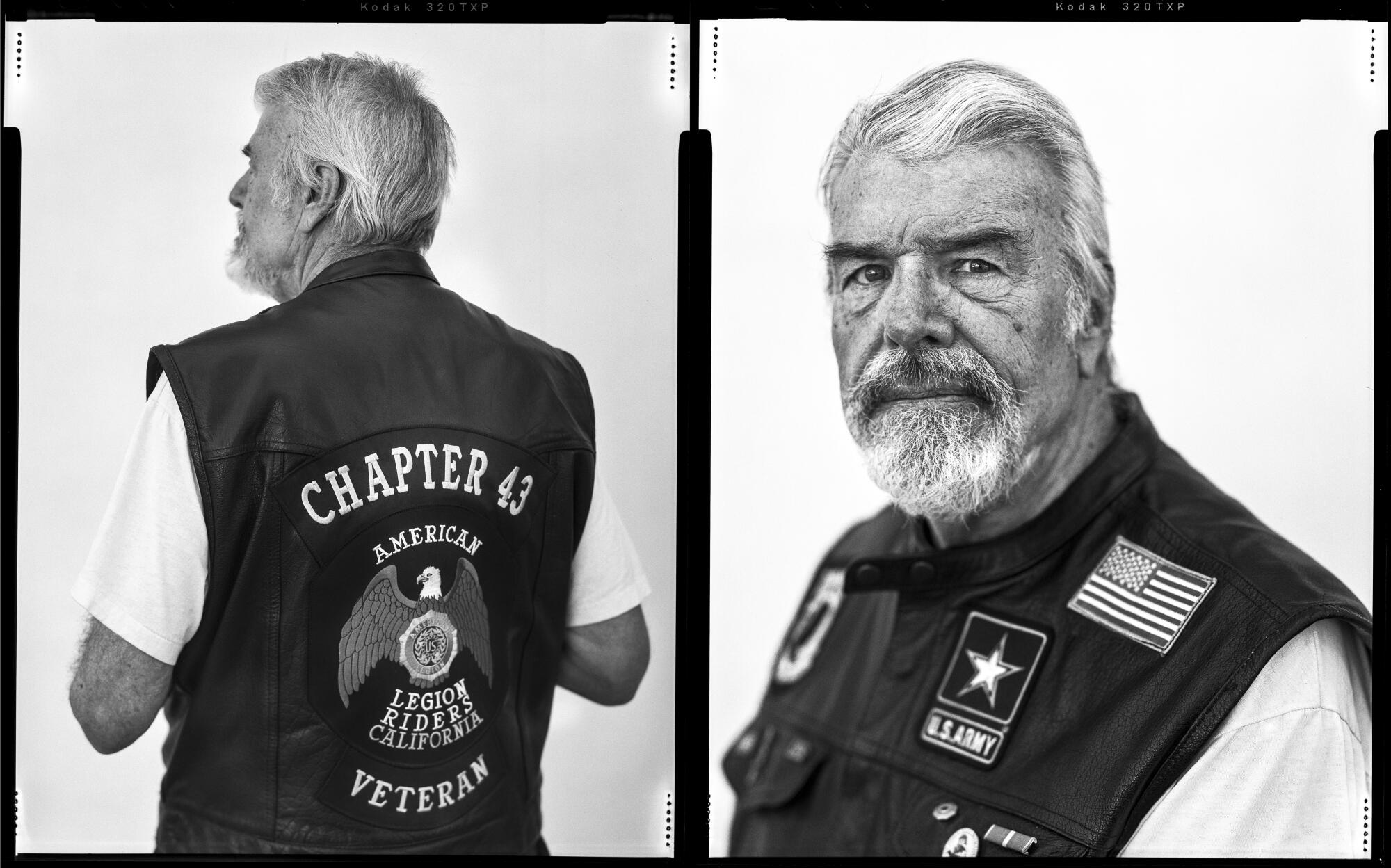

Vietnam-era Army veteran Max Thayer would love to once again enjoy the Fourth the way he did growing up in Michigan, where his family had lakeside homes.

The reality of COVID-19, which put him in the hospital for two months last year, tempers those hopes.

His experience with the disease now makes him consider freedom in a different way.

“No one is truly independent in the sense of our friends, our family, our lives [being] intertwined with other human beings,” said Thayer, 75, of West Hollywood. “We’re not a science experiment where things are absolutely clear: black and white, this is truth, this is fiction. No one’s independent, per se, and I think that we all depend on each other.”

Lynwood High School counselor Kaytan Shah notices a palpable civic unease but feels this July 4 can help heal that.

“I honestly feel Americans are going through an identity crisis,” said the 51-year-old. “And so I find Independence Day a good avenue of discussion, if we can have respectful, constructive dialogue and empathy.”

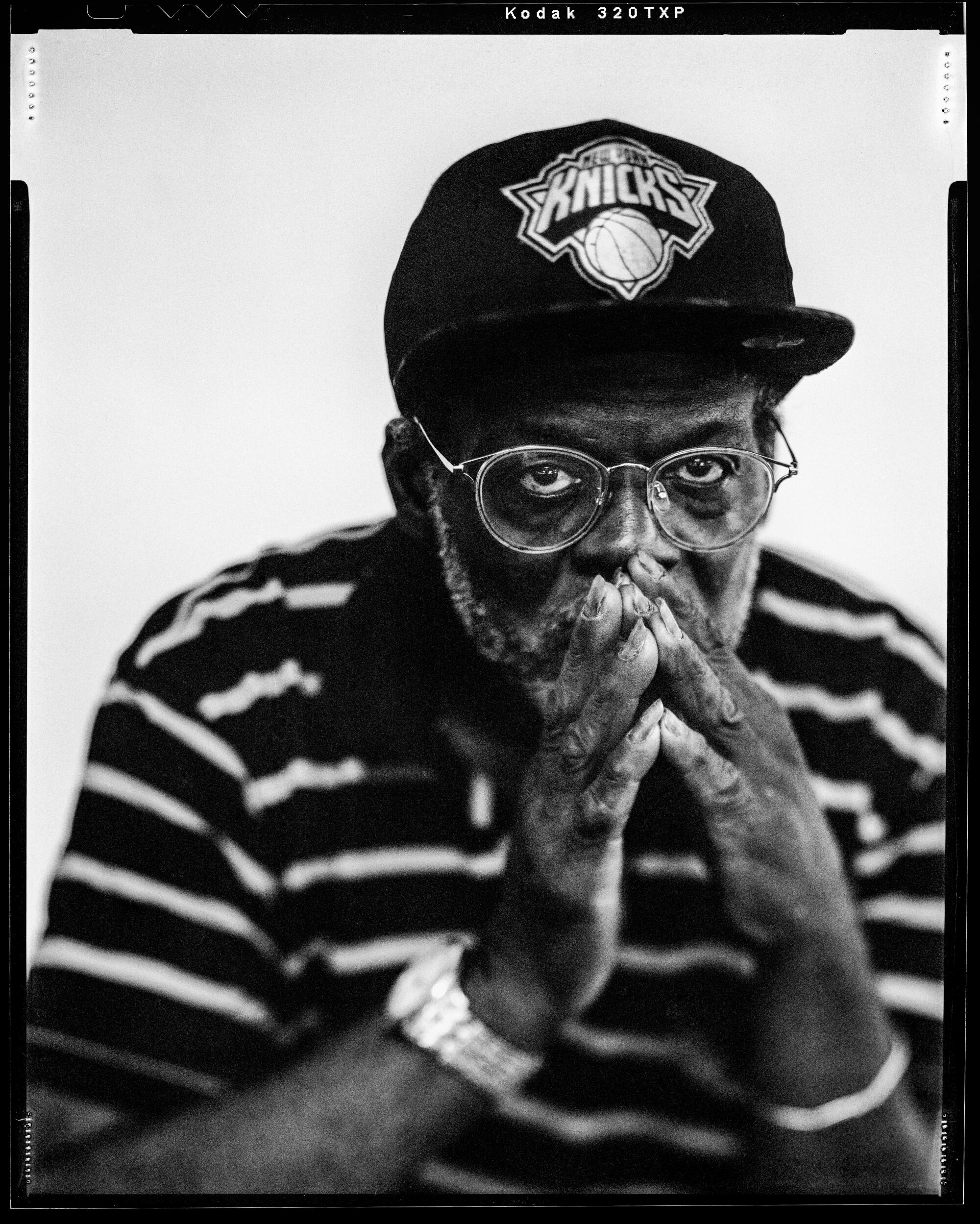

Dwight Singleton is not as optimistic. He lives in housing provided by Project Roomkey, which placed homeless Angelenos in motels and hotels during the pandemic. Los Angeles was “a ghost town” last year when he was still on the streets, he said.

“Now that people are coming back out, it doesn’t seem like it’s the same,” he said. “People are not very friendly anymore. People ... seem kind of insecure. They seem unreachable.”

The continuing pandemic also dampens any sense of joy for Dr. Jerry Abraham, who runs the COVID-19 vaccination program at Kedren Community Health Center in South L.A.

Both of his parents worked every Fourth when he was growing up in Houston.

“So it never felt always like a federal holiday, for a nurse’s aide and a gas station attendant,” the 37-year-old said.

If he was lucky, the family would get hot dogs and ice cream and chase fireworks across the city in a beat-up Datsun while “trying to connect the dots to a room full of old men signing some document that, quote unquote, freed us all.”

This time around, “I struggle knowing 600,000-plus Americans will not celebrate this July Fourth,” Abraham said. “They are gone from this world because of the terrible pandemic that wreaked havoc.”

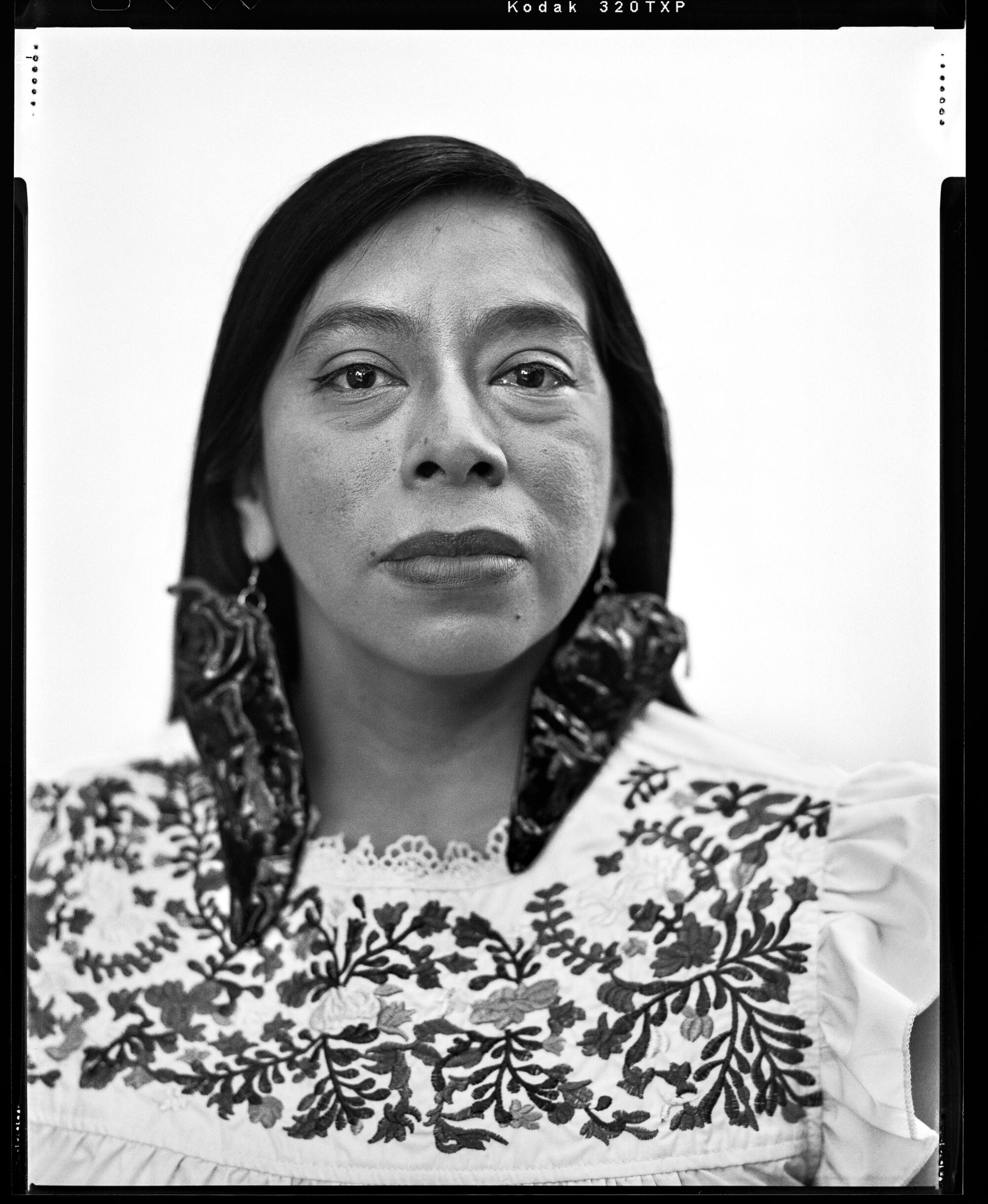

Griselda Urbina of Inglewood lost her husband, Dario, to COVID-19 on July 6 last year. Before that, she loved the spectacle of the Fourth — far different from the more muted celebrations in her native Mexico on Sept. 16.

“All the flags. All the people at the park with their barbecues,” said the 46-year-old. “And all the fireworks. I adopted the holiday because it was so joyous.”

But last year, as her husband lay dying in the hospital, “I had nothing to celebrate. I didn’t have the spirit to celebrate.” And the fireworks bothered her.

She and her four children, all of whom contracted COVID-19, mourned for months after Dario’s death. Around February, Urbina came to a realization.

“We’ve suffered a lot. We lost my husband,” she said. “What more can we lose? And I stopped feeling fear.”

So this Fourth of July, Urbina and her children will visit Dario’s grave. There will be a mariachi. There will be a small party to honor his life.

And at night, they’ll light fireworks.

Boom.

Times staff writer Alejandra Reyes-Velarde and photo editor Keith Bedford contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.