The Guatemalan Consulate in Los Angeles had a deteriorated marimba sitting in storage for over 40 years. In an effort to maintain an ancient cultural connection, the consulate sought help from one of the last marimba restorers in the city.

The instrument sat dusty and out of tune in the corner of a storage room. Its resonators were cracked, its bars unable to hold notes, and the layer of pig tripe fitted on the clay rings no longer generated a vibrating hum.

No one knows for sure why it was shut away in the Guatemalan Consulate in Los Angeles or who had built it, only that it had been years since mallets glided across its wooden keys lined up like those of a piano.

The marimba, Rosauro Esteban Chonay diagnosed, had lost its voice.

“It made me really sad to see something I love like that,” he said. “I wanted to give it life again.”

For years, the 66-year-old Esteban was one of three men he knew in L.A. who professionally restored marimbas, the national instrument of Guatemala. Then, COVID-19 killed the other two marimba healers.

In addition to taking a devastating toll on the Central American community, the pandemic shut down indoor dining at Guatemalan restaurants where marimbistas would ply their trade. Esteban went a year without playing or fixing any instrument but his own, until he received an unexpected call in March.

The call came from the consulate. Its marimba, which bore the words “Mi Guatemala,” needed serious help. And the repair needed to be done by early May — a tall order. Esteban arrived at the consulate the same day.

“For me, the marimba was born in Guatemala. But the music is for everyone, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.”

— Rosauro Esteban Chonay, professional marimba restorer

“I felt like I was going to save someone,” he said. “Like a person who’s drowning and needs help.”

Through the instrument, which looks like a xylophone with wooden legs, consular officials hope to connect Guatemalans in the U.S. to their culture and traditions back home. It’s estimated that there are close to half a million Guatemalans in California, the majority of them in L.A.

For Esteban, this was a chance to rescue an instrument that united his family in Guatemala, that brought him to the U.S. and that led him to the woman he loves.

::

In his hometown of San Francisco Zapotitlán in southwest Guatemala, Esteban’s family would sit together at lunch every day and listen to marimba music on the radio. His father, uncle and brothers all played. He started to play when he was 8.

He was a teenager when he joined Ecos del Pacífico, a marimba orchestra. It was the orchestra that took him on tour to L.A. in the late 1970s, where the 23-year-old decided to stay. Soon, he joined a marimba group and played at a Guatemalan restaurant in Westlake.

“For me, the marimba was born in Guatemala,” Esteban said. “But the music is for everyone; it doesn’t matter where you’re from.”

The actual origin story of the melodic percussion instrument, however, is debated. Some ethnomusicologists argue that the marimba was an African introduction that arrived after the Spanish. Others believe that Maya use of the marimba preceded colonialism.

“In my opinion, it has significance or maybe relationships to African marimbas, but in a way, the marimba, now it has been made or reinterpreted by the Mayan people in Guatemala,” said Juan Francisco Cristobal, a doctoral candidate in ethnomusicology at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. Cristobal was born in the town of Santa Eulalia, nicknamed la cuna de la marimba — the cradle of the marimba.

Although he moved to Colorado when he was a year old, Cristobal grew up speaking the Mayan language of Qʼanjobʼal. He learned how to play the marimba in high school and later taught it to his siblings.

In Maya communities, Cristobal said, the marimba is considered a “sacred instrument.” It’s used in religious practices, performances and during rituals.

“It’s an instrument that brings people together,” Cristobal said.

Today, the two types of marimba used in Guatemala are the single marimba, with one row of diatonic keys like the white keys of the piano, and the double marimba, which adds a row of chromatic keys (the black keys).

The development of the double marimba at the turn of the 20th century expanded the instrument’s capability and allowed marimbistas to play more popular music and gain acclaim internationally. In 1978, the marimba was named Guatemala’s national instrument.

In the years since, the marimba has been featured in some of the biggest hits in rock ’n’ roll history, including the Rolling Stones’ “Under My Thumb” and “Out of Time.” More recently, it was featured in Ed Sheeran’s hit “Shape of You.”

The instrument’s popularity didn’t come without criticism in its homeland. In places like Santa Eulalia, Cristobal said, there was a sense of cultural appropriation of the instrument while “disregarding its history, which had been so important to the rural Mayans.”

“Among the Mayan perspective, they don’t see it as a national symbol,” Cristobal said. “Rather, it’s more of this instrument that’s been part of their culture.”

::

Esteban long felt blessed by music, although he’d given it up for nearly 20 years to focus on a food truck business. He didn’t find his way back until 2006, after he began repairing marimbas and started his own group, La Perla Tuneca.

When he called a musician he knew to join, the man’s sister-in-law, Mayra Osorio, picked up the phone. She had just arrived from Guatemala, and he asked if he could call her.

“Now it’s been 15 years in music together,” Osorio said.

She played the güira, a percussion instrument, alongside the group at Puchica Guatemalan Bar & Grill in Sherman Oaks.

During the pandemic, Esteban stayed at home working on marimbas he’d built. He was invited to play at cemeteries, but with the rising death toll due to the virus, he refused, feeling that bringing people together with the marimba during such circumstances was reckless.

Over the last year, he learned that the two men he knew who restored marimbas in the area — one Honduran and the other Guatemalan — had both died from the virus. For a while, it felt, he said, like COVID-19 was taking everyone. And everything.

Even the music.

::

One day in April, Esteban labored under fluorescent lights, his eyes fixed in concentration on his patient. A sheen of sweat plastered his shaggy hair to his forehead.

“Bring me the knife,” he told Osorio, his scrub nurse in this musical surgery.

He used the dull blade to help scrape dried-out beeswax that formed a ring around a hole at the bottom of the resonators, which hung down beneath the marimba like the wooden hulls of progressively smaller ships. Fixed beneath each key, they amplified the sound of the instrument.

Osorio, his wife, handed him fresh wax and a sharpened stick to create the new ring. Esteban then stuck a paper-thin membrane of dried pig tripe over the wax to create a vibration as the keys were played. The membrane gives the lower notes a distinctive, buzzy quality.

“Con la tela, el sonido se hace brillante,” Esteban said as he tapped the key with the new membrane. The pig tripe made the instrument sound brighter.

Since March, Esteban had come to the consulate a few times a week, sometimes working on the marimba until 11 p.m. in a room where employees took their lunch breaks. At times, the only sound was the groan of wood as Esteban and Osorio removed the marimba’s innards.

Esteban, who learned carpentry from his father, had tuned dozens of keys laid out across the large wooden frame of the double marimba. Some of them he replaced entirely, bringing new ones he spent half a day making at home.

Each tap of the mallet led him to another key out of tune. He used a piece of glass to scrape the wood — in the middle to lower the note and in the corner to raise it — sending shavings drifting to the floor. He alternated between a chromatic tuner and a Yamaha keyboard to make sure he’d hit the right pitch.

When satisfied, he played songs he recalled from his childhood, including the mournfully beautiful “Luna de Xelajú,” a Guatemalan waltz composed by Paco Pérez. Xelajú is the K’iche’ Maya name for the city of Quetzaltenango.

“Está nostálgico,” a consulate worker said. Nostalgic. Soon the marimba would be ready.

Six men took their positions behind the Mi Guatemala marimba.

They wore black suits and blue ties and stood beneath pink, white and gray balloons. The flier advertising the Mother’s Day event at the Guatemalan Consulate read, “After many years of silence, our marimba will sound again.”

With three taps of the drummer’s sticks, the group of maestros, which included Esteban and his brother, began to play. They held a mallet in each hand, different sizes depending on where they stood along the instrument, and struck each key, sending it wriggling like a loose tooth.

Esteban played on the larger marimba, alongside three others, his eyes trained on the wooden keys and holding each mallet pinched between a thumb and pointer finger. In the last few weeks, he’d performed at a fundraiser, where his fingers had blistered after not playing for a year.

Inside the consulate, the group played “Ferrocarril de los Altos,” “Mi Linda Kelly” and “El Rey Quiché.”

Among the crowd of about a dozen attendees, Marta Jimenez waved a small Guatemalan flag. The 80-year-old had emigrated from her country 30 years ago, but she never forgot her beloved marimba.

“Since I was born, I’ve listened to it,” she said. “For us, the marimba is a symbol of everything.”

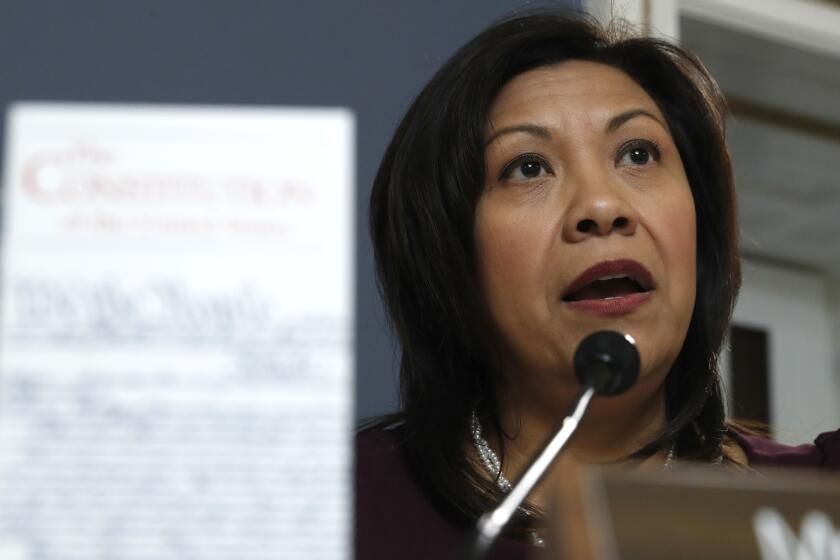

California’s Norma Torres fled Guatemala at 5. Now the only Congress member from Central America says the immigration debate is ‘very, very personal.’

Jimenez had joked that she would need a couple of drinks before she’d get up and dance. But before long she relented and spun around with someone she’d met minutes before, lured by the siren song of normality.

The group played an original composition by Esteban called “Yo ya me voy para Guatemala.” I’m leaving for Guatemala.

To the beat of the marimba, the singer crooned the words that Esteban had penned in 1980, soon after he arrived in the U.S.:

Ella es mi tierra querida

que yo no podré olvidar

“She is my beloved homeland, that I will never forget.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.