We had been walking for only a few minutes when Scott Culbertson stopped in front of a field of twisted, blackened bark.

“I haven’t been here since the fire,” the executive director of the Friends of Ballona Wetlands told me, scowling at the destruction from behind dark sunglasses.

Three months ago, this spot in the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve in Playa del Rey had been a stand of native willow trees and other vegetation where endangered songbirds would nest. Then, one sunny afternoon, a brush fire broke out and scorched five acres before firefighters could put it out.

I know because I watched from my apartment as the smoke billowed across Lincoln Boulevard and helicopters crisscrossed the air dropping water.

I wasn’t surprised that a homeless person was eventually blamed as a likely source for the fire and neither was Culbertson.

For about a year, his nonprofit and the smaller Ballona Wetlands Conservancy have been scrambling to help mitigate the extensive environmental damage caused by the occupants of an encampment that has mushroomed along Jefferson Boulevard, just west of Lincoln Boulevard.

It’s a relatively small group of homeless people, a few dozen at most. Nothing compared with the 2,000 camping a few miles away in Venice. But their forays into the fragile ecological reserve and, more frequently, the adjacent freshwater marsh have had disastrous effects that could take years to fix — and might not be fixable.

“Individuals are entering the marsh to bathe,” Culbertson told me. “Dogs are being let loose to chase wildlife. We’ve seen needles. They’re using the area as a bathroom. They’re dumping their septic tanks on the street. We’re seeing that trees are being cut down.”

But despite all that, he rejects the idea that a choice needs to be made between protecting the environment and being sensitive to the needs of homeless people.

Across Los Angeles, the housed battle the unhoused over having to share public spaces. But keeping the wetlands pristine for visitors and wildlife, and helping vulnerable people get stable don’t have to be mutually exclusive goals. And as Culbertson and I learned on our walk last week, some of those who live alongside the marsh care just as much about its health and beauty as environmentalists do.

::

We crunched along the trail, through one gate and then another, until the mud-stained wood chips gave way to hard-packed dirt. The incessant sound of traffic had slowly disappeared, replaced by the sound of squawking and cooing.

The freshwater marsh, which was created independent of the reserve in 2003 and provides natural treatment for stormwater runoff from the Playa Vista area, is a hot spot for birders. More than 250 species have been documented there so far. Culbertson, a genial, gray-haired Venice resident, is quick to point out that his background is in business, not science, but nevertheless he identified many birds he knew as we walked.

“If we were here in the morning, you need ear plugs,” he said, sticking his index fingers into his ears. “They get so loud.”

This is what Culbertson would prefer to be doing — showing off the enduring beauty of the Ballona Wetlands, something he hasn’t been able to do much of since the arrival of COVID-19.

First, the nonprofit had to shut down its in-person educational programming, eliminating some of the foot traffic that had once served as a deterrent to homeless encampments. Then, in accordance with public health orders, police stopped issuing tickets and towing people who parked overnight on Jefferson Boulevard alongside the marsh.

Within weeks, what had been a handful of vehicles became more than a dozen, leaving few places for visitors to park. Today, there’s a long line of battered RVs, cars and trucks, as well as a couple of old school buses, a delivery van and a decommissioned city bus.

People have been parked there so long that they have begun decorating. Some have planted container gardens of flowers, herbs and vegetables. Others have put out patio furniture and area rugs. One guy built a mini-gym with weights and a punching bag. I’ve seen people playing darts.

Trampled greenery now gives way to a trail of trash that leads down to the water, and a wooden fence that once separated the marsh from the roadway has been torn down repeatedly, as has signage. And tents have sprung up among the willow trees.

Workers whose job it is to monitor wildlife and do maintenance now hesitate to go to the side of the marsh near Jefferson Boulevard, especially alone, as many have been verbally accosted and followed.

“They try to avoid that area as much as possible, approaching from the water whenever possible,” said Catherine Tyrrell, president of the Ballona Wetlands Conservancy, which manages the marsh. “They don’t feel safe there.”

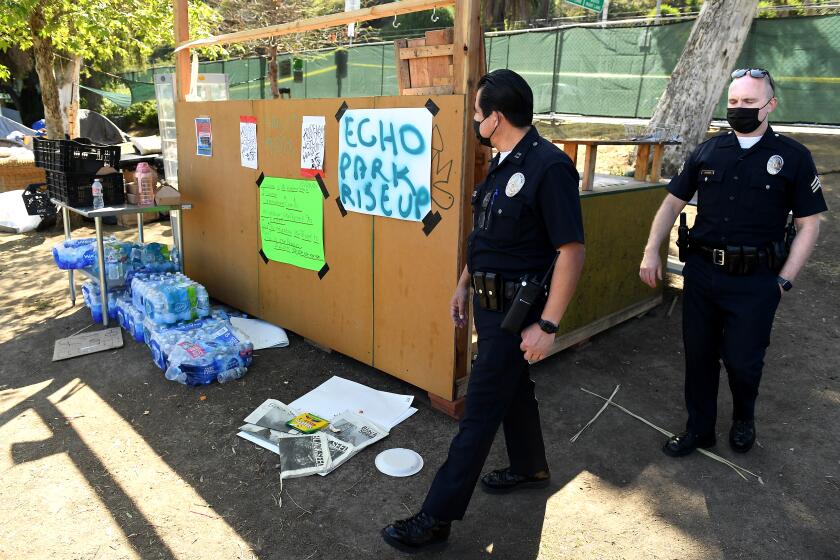

L.A.’s elected officials see the shutdown of an Echo Park encampment as a success. The homeless people who ended up in hotels don’t agree.

Chad Molnar, chief of staff for L.A. City Councilman Mike Bonin, whose district spans the wetlands, said his office is aware of what’s happening and is pursuing a “multipronged strategy” to help people living in their vehicles, protect the wetlands and preserve public access. That includes ramping up outreach and services, pursuing more safe parking and increasing sanitation services.

So far, the city has supplied trash cans, which always seem to be overflowing. But it’s the nonprofit conservancy, Tyrrell said, that’s still paying tens of thousands of dollars for trash removal.

More recently, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which manages the broader Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve, has been working with Los Angeles police to order tent campers out of the marsh. But already acres of mature, native habitat have been trashed.

“This destruction and making it so that people don’t want to visit or are afraid to visit, that is not OK with me,” Culbertson told me.

::

It’s not OK with many of the homeless people who live there either. Chief among them Wendy Lockett.

We had just rounded the corner out of the marsh and onto Jefferson Boulevard when she approached us, her dark hair pulled back into a ponytail.

“I’m the one that writes the notes,” she said proudly, pointing to a hand-painted sign leaning against one of the few sections of wooden fence that’s still intact. It read: “DO NOT THROW TRASH OVER THIS FENCE!! IF I CATCH YOU, I WILL HUNT YOU DOWN AND EAT YOU FOR BREAKFAST.”

As if on cue, a pickup truck towing a dumpster heaped with trash inched by.

Lockett said she has been homeless for two years, but only living in her white van alongside the marsh for about six months. Some people, she said, “just want to be pigs,” but many others have been working to keep the place clean.

“This is a natural reserve. It’s beauty at its finest. There’s people that break the fence and we’re trying to build it,” Lockett assured Culbertson, pointing at a pile of newly purchased lumber. “Just because you’re forced to live outside doesn’t mean you got to be a pig about it. No one owes you anything. The world is not your oyster. So, you know, clean up after yourself, like you would if you’re in your own home.”

A few minutes later, another resident of the encampment stopped us.

At a new city-run ‘safe ground’ in Sacramento, there is a focus on building community to get homeless people from encampments to stick around for help.

“Are you a bird watcher?” Stephen Gilbert asked my camera-carrying Times colleague Al Seib. “There’s this mohawk bird and I want to know what it is.”

Gilbert and his wife have been camping in their RV next to the marsh since April. The pair work and are saving up enough money so they can travel. “We’re trying to see the world that I’ve never seen before because I’ve been in L.A. and all I see is concrete,” he explained. “I want to see nothing but green. Mountains, rivers.”

Culbertson nodded appreciatively. “I’m going to put a bird guide on your windshield on your car,” he told Gilbert, “and you’ll be able to identify what you’re seeing.”

::

We ended our walk a short time later, the sun high in the sky by then. Culbertson was thoughtful about what he had seen and what he had heard, reiterating that they are human beings who need services and housing.

While he had no solutions for the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the marsh, he said he would be fine if the city blocked off a dozen spaces so some people could continue to park there indefinitely.

“Provide services. Toilets. But it has to be managed,” Culbertson said. “There’s got to be somebody to pick up the trash.”

A plan for how to solve Venice’s homeless crisis has emerged from behind-the-scenes talks among a coalition of Venice activists, city officials and deputies of the area’s city councilman.

I agree. That’s because, despite all the promises from politicians to move tens of thousands of people into some as yet unidentified supply of housing, I seriously doubt most of the homeless people we see living on our streets will be going away anytime soon.

That means we all must find a way — a better way, a more controlled way — to share public spaces in Los Angeles. Even in, yes, sanctioned encampments by the beach and in neighborhoods across the county.

With California reopening its economy this week and Bonin vowing to start slowly clearing the boardwalk of homeless encampments in Venice, there’s no better time than now to figure it out.

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.