For widows, orphans cheated by Tom Girardi, ‘Real Housewives’ riches add to the pain

Within weeks of the crash of Lion Air Flight 610 off the coast of Indonesia, Tom Girardi’s men arrived in Jakarta knocking on the doors of the victims’ families.

Mr. Girardi is one of the best attorneys in America, they told the newly widowed and orphaned in 2018. Sign up with him and you could get millions from the plane manufacturer Boeing. They handed out glossy booklets touting Girardi’s quarter-century of taking on airlines and plane manufacturers and the billions he had won for his clients.

It was a persuasive pitch, but for five grief-stricken families, it turned out to be a lie. Girardi did wrest enormous settlements from Boeing in the name of their loved ones, but once wired to his firm’s bank accounts, at least $3 million due to the victims’ relatives went to Girardi’s own purposes.

“This is rightfully ours, not Girardi’s,” said Septiana Damayanti, whose husband died in the crash, leaving her to raise their two daughters, ages 5 and 3. “I’m exhausted. I thought I could use the settlement money for the children. At least they could’ve gotten a good education, that they’d not need to worry.”

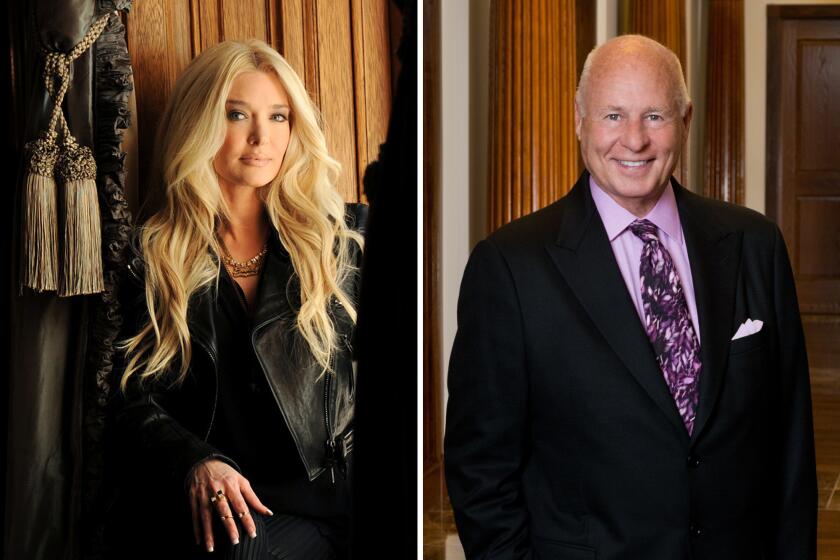

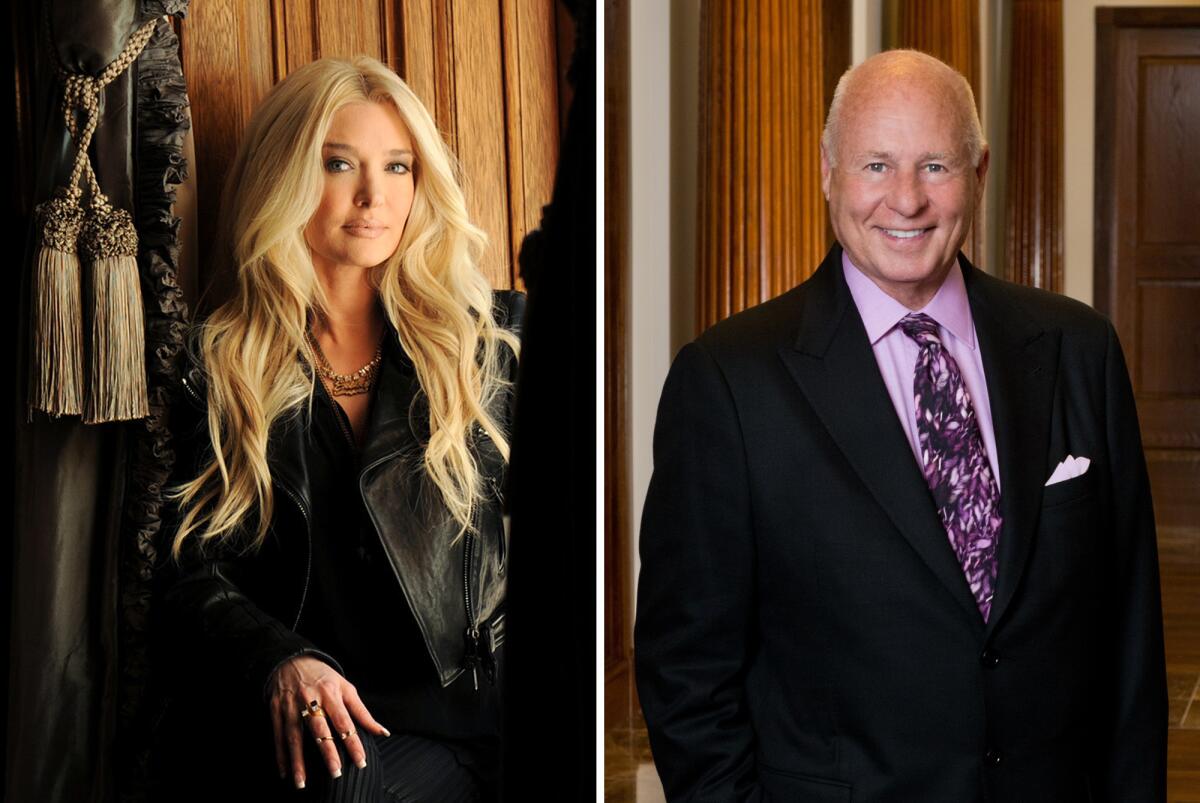

Bankruptcy trustees have accused the reality star of concealing assets for her husband and are dispatching investigators to comb through her belongings and accounts.

Damayanti will be one of several clients who have accused Girardi of misconduct who will be tracking the new season of “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” hoping for evidence that can help their case. The Bravo show, which stars Girardi’s estranged wife, Erika, and premieres Wednesday, will focus on the scandal.

Girardi owes tens of millions of dollars to scores of former clients, fellow attorneys, and vendors of his once prominent law firm, Girardi Keese. But the swindling of the Lion Air orphans and widows stands apart for its brazenness and for the role the missing settlement money played in Girardi’s downfall late last year.

‘Did you actually make sure that the clients were paid?’

A Chicago attorney serving as local counsel in Girardi’s suits against Boeing noticed what was going on after the settlements were finalized in February and March.

“Tom was being pretty cagey when it came to the money,” the Chicago lawyer, Jay Edelson, recalled. Initially, he figured Girardi just didn’t want to share the fees, a somewhat common occurrence in such cases, but when Edelson kept pressing, Girardi made a comment that unnerved him.

“Just give me more time, I’m going to not just pay your fees, but I am going to pay you even more,” Edelson recalled Girardi telling him. The remark was “a red flag” suggesting the L.A. lawyer was using the Indonesians’ settlements as a slush fund, Edelson said, and prompted him to ask Girardi, “Did you actually make sure that the clients were paid?”

Receiving no satisfactory response, he filed a federal lawsuit against Girardi accusing him of using the victims’ settlement money to finance a “public image of obscene wealth” for him and Erika Girardi, a pop singer known as Erika Jayne. Edelson also notified the federal judge overseeing the Lion Air litigation.

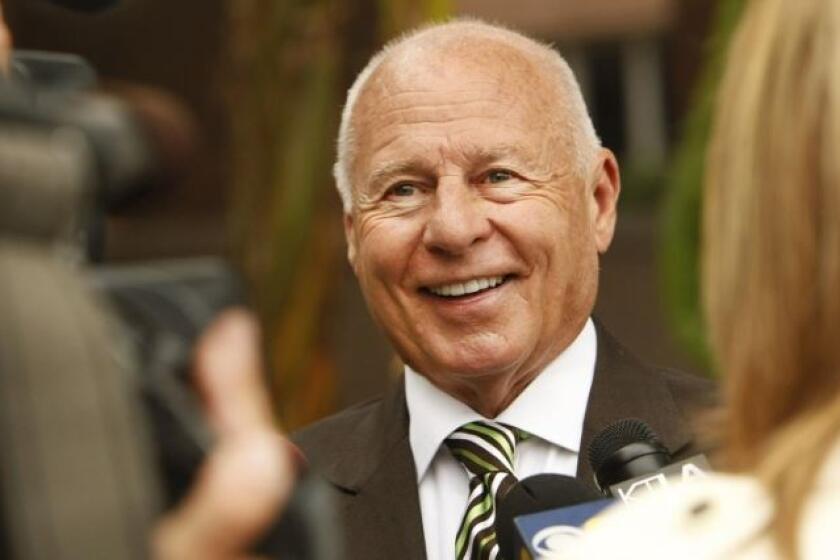

“Why wouldn’t everything be paid to the plaintiffs upon receipt of the money from Boeing?” Judge Thomas Durkin demanded of the 81-year-old lawyer during a December hearing.

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

Neither Girardi nor a criminal defense attorney he brought to the hearing offered an explanation. Durkin immediately referred the matter for criminal investigation by the U.S. attorney’s office in Chicago.

“Half a million dollars for any one of these families is a significant amount of money, life-changing money, given the tragedy they went through and trying to carry on after that,” Durkin said before freezing Girardi’s assets and holding him in civil contempt.

‘COVID had nothing to do with this’

By then, the Indonesians had been waiting for the money for almost a year. After they signed settlement papers in late winter, they were told the money would be wired within 30 days.

When it didn’t come, the families contacted Girardi, other lawyers at Girardi Keese and even the chief financial officer of the law firm. Girardi’s representatives blamed the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They said at the time that the coronavirus is increasing so offices are closed, they cannot wire money,” said Multi Rizki, whose father died in the crash.

Floyd Wisner, an aviation attorney who was then representing other Lion Air families, scoffed at the excuse.

“COVID had nothing to do with this,” said Wisner, now representing the defrauded Indonesians. “I was working from home. It’s an easy wire transaction.”

“It seemed to us that he was robbing somebody to pay somebody else. ... In Indonesia, this would be theft and embezzlement.”

— Septiana Damayanti, whose husband died in the 2018 Lion Air plane crash

As the families tried to understand the situation, they were in close contact. The Lion Air flight, a Monday morning commuter route, carried many professionals. The families of three judges, including Rizki’s father and Damayanti’s husband, were Girardi clients, and they began to share with each other what they learned from their online research.

Bias Ramadhan, whose mother, also a judge, died on the flight, said he quickly brought himself and the rest of the group up to speed on Girardi’s life, including “Erika Jayne’s musical career, Real Housewife of Beverly Hills and stuff.”

“So many people making videos, making podcasts, making Twitter accounts,” Ramadhan said.

The more he learned about Girardi — with his Pasadena estate, private planes and glitzy parties — the more repulsed he became.

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

“The way of life of Tom Girardi and his wife just doesn’t make sense for me, as someone coming from Indonesia,” he said. “The way he spent money is just mind-blowing, actually.”

Meanwhile, he continued pressing for the money from Girardi and his team.

Pressuring Girardi for payment — and threatening to alert State Bar

“Good day Mr. Tom,” Ramadhan wrote in an October email shared with The Times. “I just want an update when will our settlement be fully settled? We have wait for so long.”

The pressure worked — to a point. Girardi’s firm sent checks of less than $100,000 to some of his clients.

Girardi’s associates promised the full amount was on its way, but the Indonesians felt increasingly desperate. In November, after reading that Erika Girardi had filed for divorce, Ramadhan wrote that he was considering reporting their lawyer to the State Bar of California.

“Where is our money? I need an explanation why we must wait to get portion of that money,” he wrote in an email.

Before a response came, other former clients and vendors forced Girardi into bankruptcy and the lawyer’s relatives told a judge he was suffering from dementia. The Indonesians are now in line for compensation with dozens of other creditors. Bankruptcy trustees are in the process of liquidating what remains of Girardi’s estate. His assets include legal fees in thousands of pending cases. It’s unclear what individual creditors will receive at this time.

“It seemed to us that he was robbing somebody to pay somebody else. Like he was using settlement money from Case A to pay for Case B, and using money from Case C to pay for Case B,” Damayanti said. “That’s outrageous. ... In Indonesia, this would be theft and embezzlement.”

Money needed for tuition, childcare, daily expenses

The lack of funds has affected the Lion Air crash victims’ extended families. Rizki said his father, a judge for about 25 years, was the oldest son with six siblings and was expected to support relatives in addition to providing for his wife and children.

“I need to replace that. I need to continue his legacy,” Rizki said. “For my little brother, we need to pay for his tuition fee and for my mother, we need money for her daily expenses.”

In March, the State Bar of California brought charges against Girardi and cited the misappropriation of the Indonesian clients’ money as a basis for the disciplinary action. Now in a court-approved conservatorship, Girardi has not mounted a defense to the Bar’s charges, and his brother’s attorney recently told the Bar that Girardi will never practice law again.

For Ramadhan, whose father died years before his mother’s death in the crash, the waiting seems interminable.

“I have three siblings and I have no mother, I have no father, and my grandmother and grandfather are already dead,” he said. “I have to take care of [my siblings].”

His family keeps asking about the status of the case and the prospect of securing compensation from Boeing.

“It is kind of difficult to explain,” he said, adding, “I don’t want to tell them I got duped by some old man in America.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.