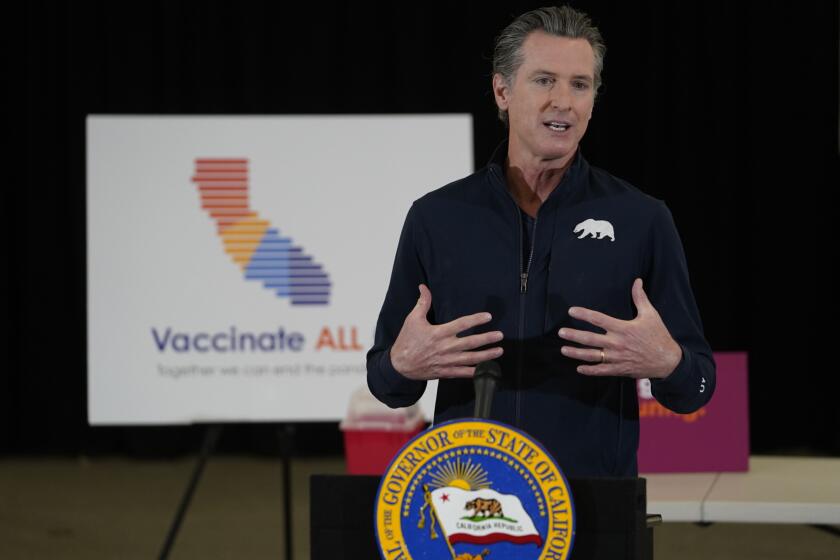

How a $1-million donation on behalf of Newsom was hidden in plain sight

SACRAMENTO — The $1-million donation came as the COVID-19 crisis was unfolding, a charitable gift given on behalf of Gov. Gavin Newsom last year. But unlike with other so-called behested payments, philanthropic contributions made at the request of an elected official, the source of the donation was concealed in public disclosures required under a state law meant to ensure transparency and limit undue influence in government.

The seven-figure gift was made from a donor-advised fund, a type of charitable giving account offered by some nonprofit foundations and for-profit investment firms that provides more generous income tax deductions and anonymity. The practice of routing behested payments through such accounts is little known, even to the most seasoned political insiders, but it is raising concerns with government watchdogs who say it allows unidentified donors to avoid scrutiny when making charitable contributions on behalf of politicians with whom they may be trying to curry favor.

In required filings with the California Fair Political Practices Commission, Newsom’s office reported that the $1-million donation was made in April 2020 from the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The foundation confirmed to The Times that the money was not from the charity itself, but was made at the request of a person or company with a donor-advised fund at the organization.

“The public needs to know who the original donor is,” said Bob Stern, a co-author of the state’s Fair Political Practices Act, approved by voters in 1974 and updated in 1997 through legislation to include behested payments. “This clearly wasn’t anticipated when the law was passed.”

Public charities can offer organizations, families and individuals the ability to open donor-advised funds that allow for immediate tax write-offs, a sort of savings-account-style approach to charitable contributions. Donor-advised funds are the fastest-growing vehicle for charitable giving but have come under scrutiny for having too little oversight over how and when the funds are used, with assets allowed to accrue indefinitely.

Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) and nonprofit organizations relying on donations have been pushing for changes in state law that increase transparency requirements for foundations offering donor accounts. The use of donor-advised funds to provide anonymity for behested payments, however, raises new questions about whether it undermines the Fair Politics Practices Act.

“Donor-advised funds can be used to hide things, that’s not the only reason people use them, but it’s one reason,” said Jan Masaoka, chief executive officer of the California Assn. of Nonprofits.

And, critics say, they present a significant obstacle to keeping the behested payments process transparent.

State records show that so-called “behested payments” spiked in 2020 compared to the year prior, when companies gifted $12.1 million on Gov. Newsom’s behalf.

Under California law, when an elected official or someone acting on their behalf asks that a donation of $5,000 or more in cash or services be directed to a nonprofit or government agency, that contribution is considered a behested payment and must be reported to the FPPC. There is no limit on how much can be donated by organizations or individuals at the behest of an elected official, another aspect of the practice that has drawn criticism from open government groups.

Though behested payments are earmarked for noble causes, the companies asked by elected officials to donate often have multimillion-dollar contracts or other business before the state, creating the appearance of a pay-to-play system. Because state law does not address the use of donor-advised funds in making behested payments, or set additional disclosure requirements for those who use them, the public is unable to determine whether donors whose identities are shielded by such accounts stand to benefit from charitable contributions made on behalf of a politician.

The extent by which donor-advised funds have been used to make behested payments to Newsom and other elected officials in the state is unclear. No notation is made in state filings when a donor-advised fund is used.

“From a public confidence and trust perspective, the more transparency around all sources of behested payments, wherever possible, the better,” said Mindy Romero, the director of the Center for Inclusive Democracy at USC.

Newsom’s office declined to comment on The Times’ questions for this story.

“The process is transparent, and we abide by all the rules and regulations that apply, including the timely sharing of any such payments, which are available for the public to review,” Newsom spokesman Daniel Lopez said in a general statement about behested donations.

Last year, Newsom raised $226 million in behested payments, an unprecedented amount spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and a willingness among companies and philanthropists to help fund government and charitable programs. That money was directed by Newsom to aid programs benefiting Californians during the pandemic, including funding to address homelessness and a public safety campaign promoting the importance of wearing masks.

State filings appears to show the top donor of behested payments to Newsom in 2020 was tech giant Facebook, which gave $27 million for gift cards that went to front-line healthcare workers and for public health ads.

But a closer analysis of state records by The Times shows the top donor was, in fact, Kaiser Permanente with $34.5 million donated in 2020 on behalf of Newsom, a total that includes a $9.75-million gift listed under Kaiser’s name and an additional $25 million that the company gave on behalf of Newsom using donor-advised funds it holds at the California Community Foundation and East Bay Community Foundation.

Kaiser and Newsom’s office both promoted the $25-million gift in press releases and news conferences — the donation was directed to the governor’s program helping those experiencing homelessness. When The Times asked Kaiser why the donation was not reflected in state filings, a representative for the healthcare giant pointed The Times to the charitable organizations through which the donation was made.

There is no limit on how much a company or individual can donate on behalf of an elected official. Newsom helped secure $226 million last year.

A Kaiser spokeswoman said the company often gives charitable contributions through donor-advised funds and there was no intention of hiding the donations since it was announced publicly. It is the responsibility of the governor’s office to report the donations to the FPPC, the spokeswoman noted.

A FPPC spokesman said donor-advised funds are not addressed in current regulations governing behested payments and declined to comment on examples raised by The Times.

“What we can say is the principle in California is the true source of funds is to be disclosed and that is a long-accepted and established principle,” FPPC spokesman Jay Wierenga said.

The California Community Foundation said seven other donations on behalf of Newsom last year were from the foundation itself and not from donor-advised funds. The East Bay Community Foundation, which did not respond to The Times’ request for information, made a second donation — for $100,000 on behalf of Newsom last year — but it’s unclear whether that also came from a donor-advised fund.

Marketing material from the East Bay Community Foundation promotes the opportunity to donate anonymously, noting that donor-advised funds “offer donors the benefit of 100% anonymity, unlike a private foundation.” Critics say unidentified contributions to a nonprofit may not raise the public’s concerns, but that they should when large checks are written at the request of an elected official.

Fidelity Charitable and Vanguard Charitable, both of which offer donor-advised funds, declined to identify the donors who made behested payments last year that were directed to helping students in the state with remote learning during the pandemic. The Fidelity Charitable donor gave $250,000 on behalf of Newsom, while the Vanguard Charitable account gave $100,000.

“The privacy of our donors is one of our highest priorities and as a policy, we do not discuss individual donors or nonprofits,” said Stephen Austin, a spokesman for Fidelity.

A Vanguard spokeswoman said donors have “the right to choose” whether they wish to be acknowledged for their gift.

The Silicon Valley Community Foundation, which arranged the $1-million donation from a fund-holder last year, said a second charitable gift for $50,000 was made through a donor-advised fund on behalf of the governor in May 2020. The identity of the donor, however, is not being released.

“Unfortunately, I am unable to provide any further information beyond that,” Chau Vuong, a spokesperson for the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, said in an email. “We are not able to disclose our donors’ identities or their fund names, and we do not comment on our donors’ philanthropic activities without their expressed permission.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.