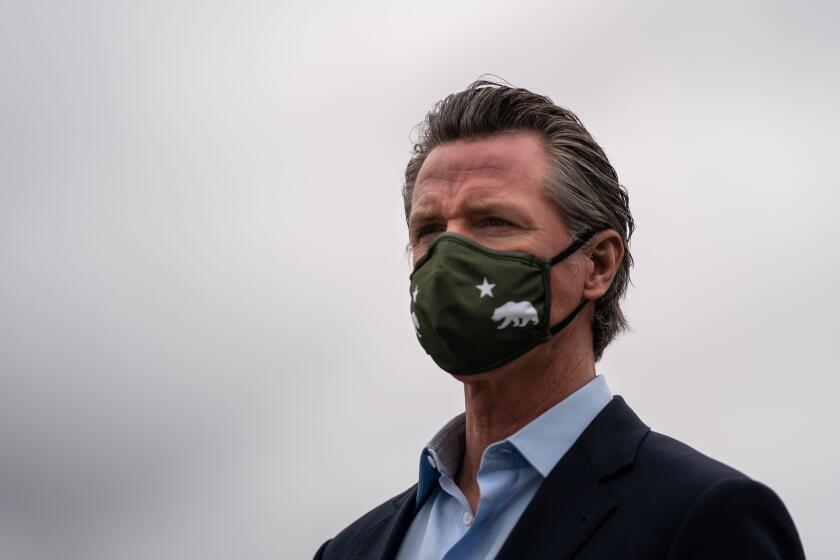

Gov. Gavin Newsom to face recall election as Republican-led effort hits signature goal

SACRAMENTO — Propelled by growing voter frustration over California’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a Republican-led drive to remove Gov. Gavin Newsom from office collected enough voter signatures to qualify for the ballot, state officials reported Monday, triggering for only the second time in state history a rapid-fire campaign to decide whether to oust a sitting governor.

Recall backers submitted more than 1,495,709 verified voter signatures — equal to 12% of all ballots cast in the last gubernatorial election — meeting the minimum threshold to force a special recall election, according to a tally released by Secretary of State Shirley Weber. Barring intervention by the courts, Newsom will face a statewide vote of confidence by year’s end.

“We knew we gathered enough signatures, and now it’s time to turn it over to the voters,” said Dave Gilliard, one of the strategists leading the effort to oust Newsom. “We’re very confident that they’re going to want to change direction in California and remove Gavin Newsom and go with someone else.”

Newsom’s advisors expressed confidence that the governor will defeat the attempt to remove him from office and criticized the recall effort as the work of far-right supporters of former President Trump.

The governor, who appeared prepared for Monday’s announcement, quickly took to Twitter to defend his record.

“This Republican recall threatens our values and seeks to undo the important progress we’ve made — from fighting COVID, to helping struggling families, protecting our environment, and passing commonsense gun violence solutions,” Newsom said. “There’s too much at stake.”

Though recent opinion polls showed that only 40% of California voters support recalling Newsom, an indication that the effort might fail, the success of the recall campaign in gathering enough valid signatures for a special election delivers a blow to Newsom, one of the nation’s most prominent and politically ambitious Democrats, who raised his national profile as a liberal foil to Trump.

In all, Newsom’s critics gathered 1,626,042 valid voter signatures on recall petitions, according to the report issued Monday, which contains information collected from elections officials in California’s 58 counties as of April 19. Some signatures remain unexamined. The final report will be issued by Friday.

Before the recall petition can be certified by Weber, voters who signed the petitions will be given time to withdraw their signatures, and state officials will crunch the numbers on the cost to conduct the election, steps that could take up to three months to complete. Only then can Weber issue her official certification, triggering action by Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis to call an election within 60 to 80 days.

October or November? Key changes to California election law make the timing unclear for a recall election against Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Voters will decide whether Newsom is recalled and, if he is removed from office, who should replace him. Newsom is barred from being listed among the candidates who can be considered if the recall passes.

Two and a half years ago, Newsom won the governor’s office by the largest margin in modern history, capping the telegenic Democrat’s steady rise to the pinnacle of California politics that began in 1996, when San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown appointed him to the city’s Parking and Traffic Commission.

The son of an appellate court judge with deep ties to San Francisco’s most affluent residents, Newsom ascended quickly to a seat on the city’s Board of Supervisors, two terms as San Francisco mayor and, after abandoning a fledgling run for governor in 2010, eight years as California’s lieutenant governor.

Voters surveyed by the Public Policy Institute of California were largely split along party lines with 79% of Republicans in support of the recall and the same share of Democrats in opposition.

Enveloped in an air of inevitability, Newsom dominated the 2018 governor’s race by trouncing a field of Democratic rivals that included former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, former state Treasurer John Chiang and former state schools chief Delaine Eastin, as well as a little-known Republican challenger, businessman John Cox. Newsom’s campaign stoked whispers and persistent speculation of a future White House run.

But Newsom’s star dimmed this summer as criticism of his response to the pandemic intensified, and he now finds himself fighting for survival.

The recall vote opens up the possibility that a Republican could be elected to replace Newsom, a scenario that took place in 2003. That year, California voters — soured by rolling power outages, budget cuts and a car tax hike — recalled Democratic Gov. Gray Davis from office and elected Hollywood action star Arnold Schwarzenegger, the last Republican to serve as the state’s chief executive.

The spectacle of the 2003 recall election fascinated people across the country, who were intrigued by California’s reputation as a far-out haven for sun-baked dreamers, celebrities and Hollywood wannabes — and political absurdity. More than 130 candidates hoping to replace Davis crammed the ballot, among them Hustler magazine founder Larry Flynt, former Major League Baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth, Huffington Post co-founder Arianna Huffington and “Diff’rent Strokes” star Gary Coleman.

The attempted recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom will go before voters on Sept. 14. Here are the details.

Californians already trying to survive the disorienting realities of the COVID-19 pandemic may face a similar political carnival in 2021. Local officials from across California believe the cost of conducting the recall election could run as high as $400 million.

Democratic leaders have publicly vowed to support Newsom and, along with the governor’s advisors, have described the recall effort as the handiwork of ambitious Republican politicians and pro-Trump, anti-mask, anti-vaccine extremists.

The effort began last spring, spearheaded by Orrin Heatlie, a retired sheriff’s sergeant from Yolo County. It is the sixth attempt to recall Newsom since he took office in January 2019; the previous five, including two others by Heatlie, fizzled with little support and even less notice.

“The People of California have done what the politicians thought would be impossible,” Heatlie said in a statement posted on the recall campaign’s website. “Our work is just beginning. Now the real campaign is about to commence.”

The recall efforts were fueled in large part by the festering animosity California’s conservative minority holds against Newsom and his progressive agenda, a virulence highly concentrated among supporters of Trump. The petition that placed Newsom’s recall on the ballot focused on well-worn GOP grievances in the deep blue state, blaming Newsom for California’s high taxes and homelessness crisis, and criticizing him for protecting immigrants who enter the county illegally and for halting executions.

This is the week political watchers expect enough validated voter signatures to force a recall election against Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Conspicuously absent from the petition is criticism of Newsom’s response to the pandemic, which was in its infancy when recall proponents launched the effort.

But the governor’s policies to combat COVID-19 provided the blast of oxygen necessary to bring the recall to life.

Shortly after the onset of the pandemic, Newsom enjoyed soaring job approval ratings following his initial response, including imposing the nation’s first statewide stay-at-home order in mid-March.

However, his high marks began to plummet, as did those of other governors across the nation. Californians grew frustrated with government-mandated restrictions to stem the spread of the virus, actions that devastated businesses, put millions out of work and forced schoolchildren into distance learning programs.

Newsom’s public image took a major hit in November, when he attended a lobbyist’s birthday party at the upscale French Laundry restaurant in Napa Valley after pleading with Californians to stay home and avoid multifamily gatherings. Supporters of the Republican-led recall effort seized on the misstep, accusing the wealthy governor of hypocrisy and of enjoying the everyday freedoms and luxuries that were barred for many in the state.

Newsom acknowledged his decision to visit the Michelin-starred restaurant with other families may diminish his moral authority on COVID-19.

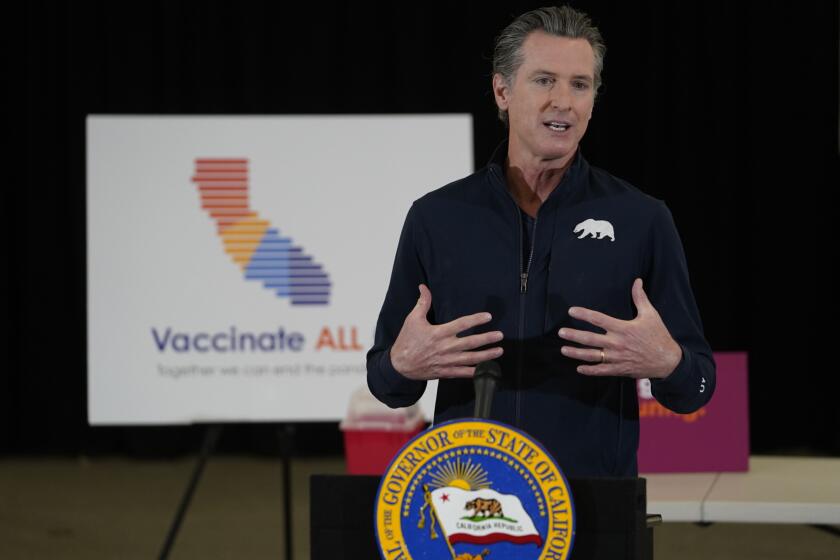

Newsom’s political fortunes are tied, at least in part, to California’s ability to rebound from the pandemic by the time of the recall election. If children are back on campuses and people are widely vaccinated, Democratic and independent voters may view their governor more favorably at the polls.

UC San Diego political scientist Thad Kousser said the situation looked bleak for Newsom just a few months ago when California was overwhelmed by a surge in COVID-19 cases, businesses were suffering and in the aftermath of the French Laundry episode.

Much has changed, however. California’s coronavirus case rate is now the lowest of any state in the nation, schools are reopening, the state could see a $15-billion tax revenue windfall, and Newsom has predicted the state’s economy will fully reopen in mid-June.

“Its fate today looks much less possible than it did when when this recall drive began in earnest,” Kousser said. “But if there’s anything we’ve learned last year it is that things could change dramatically in another four months.”

Newsom earlier this month announced the June 15 target for that return to normality. The governor said he intends to lift business restrictions and fully reopen the state economy, so long as vaccine supply remains sufficient and hospitalization rates are stable.

Barring the emergence of a more dangerous coronavirus variant that resists vaccines, a shortage in vaccine supply or some other major failure, the chance of hitting that summer reopening date seem high as more Californians become inoculated, health officials say.

State officials in February estimated that a large swath of Californians — as many as 38% — had antibodies either from catching the virus or from vaccines. The Newsom administration has drastically expanded vaccine eligibility since then, opening access April 15 to all residents 16 and older.

More than 26 million vaccine doses have been administered in California, and more than a quarter of the population is fully vaccinated.

It’s unlikely that another coronavirus surge would overwhelm California’s hospital system, experts say

Still, Newsom’s job approval rating among California voters has suffered, according to two independent political polls released in February. The surveys found that roughly half of voters gave Newsom good marks, down from 64% earlier in the year.

In a Public Policy Institute of California poll released in March, 56% of voters said they opposed the recall, and 40% supported it; the remainder were undecided. The percentage of those who favored ousting Newsom was slightly above the support for Trump in California in the November election, when he received 34% of the vote.

That hasn’t deterred Republicans from lining up to replace Newsom.

Former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer earlier this year announced that he would challenge Newsom, either in a recall campaign or when Newsom is up for reelection in 2022. Cox, who was defeated by Newsom in the 2018 general election, expressed similar plans. Former Northern California Rep. Doug Ose, a Republican who left office in 2005, is also in the running, as is reality television star and Olympic gold-medalist Caitlyn Jenner.

Two familiar faces who were candidates in the 2003 recall election have also joined the race: former adult film actress Mary Carey and L.A. billboard icon Angelyne.

Others caught up in the swirl of rumors and speculation about potential candidates include Richard Grenell, who served as ambassador to Germany and acting director of national intelligence in the Trump administration.

One pivotal question that remains unclear is whether a Democrat will jump into the race, either in support of ousting Newsom or hoping to serve as a safety valve to block a Republican from being elected if Newsom is recalled.

Times staff writers Seema Mehta and John Myers contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.