Judge’s skid row order leaves L.A. officials and housing developers scrambling

A federal judge’s explosive order calling on Los Angeles to offer shelter or housing to every homeless person on skid row is setting off growing alarm that his decision could upend years of homeless policy in the city, stalling construction of dozens of housing projects.

Earlier this week, Judge David O. Carter threw a major wrench into L.A.’s plan for addressing homelessness, demanding that Mayor Eric Garcetti take roughly $1 billion he had been planning to spend on the crisis and put it into an escrow account. At the same time, he issued a blistering critique of the Proposition HHH program, the 2016 bond measure whose projects have been beset by delays and rising costs.

Some HHH developers, who already have projects under construction or are months away from breaking ground, said they fear Carter intends to raid HHH funding and direct the money elsewhere.

The order is also drawing fresh criticism from city leaders, who say it lacks a basic grasp of how municipal budgets work.

“The idea that the city has billions of dollars just lying around that are not being used right now, that we could just write a check and put it into an escrow account, doesn’t make sense,” said Councilman Paul Krekorian, who heads the council’s budget committee.

A federal judge has ordered the city and county of Los Angeles to offer some form of shelter to skid row’s entire homeless population by October.

The scramble to decipher Carter’s order, and decide when and how to push back, has consumed much of the city’s energy since Tuesday, when the judge instructed L.A. officials to offer every homeless resident of skid row shelter or housing by mid-October.

Carter, who chided the city for failing to show a sense of urgency, called for an immediate halt to all sales and leases of city property for projects that were not in progress as of Tuesday.

He demanded audits of an array of homelessness programs, including Proposition HHH, which is expected to provide funds next year for more than 5,600 units of housing that offer support services, such as mental health or substance abuse counseling.

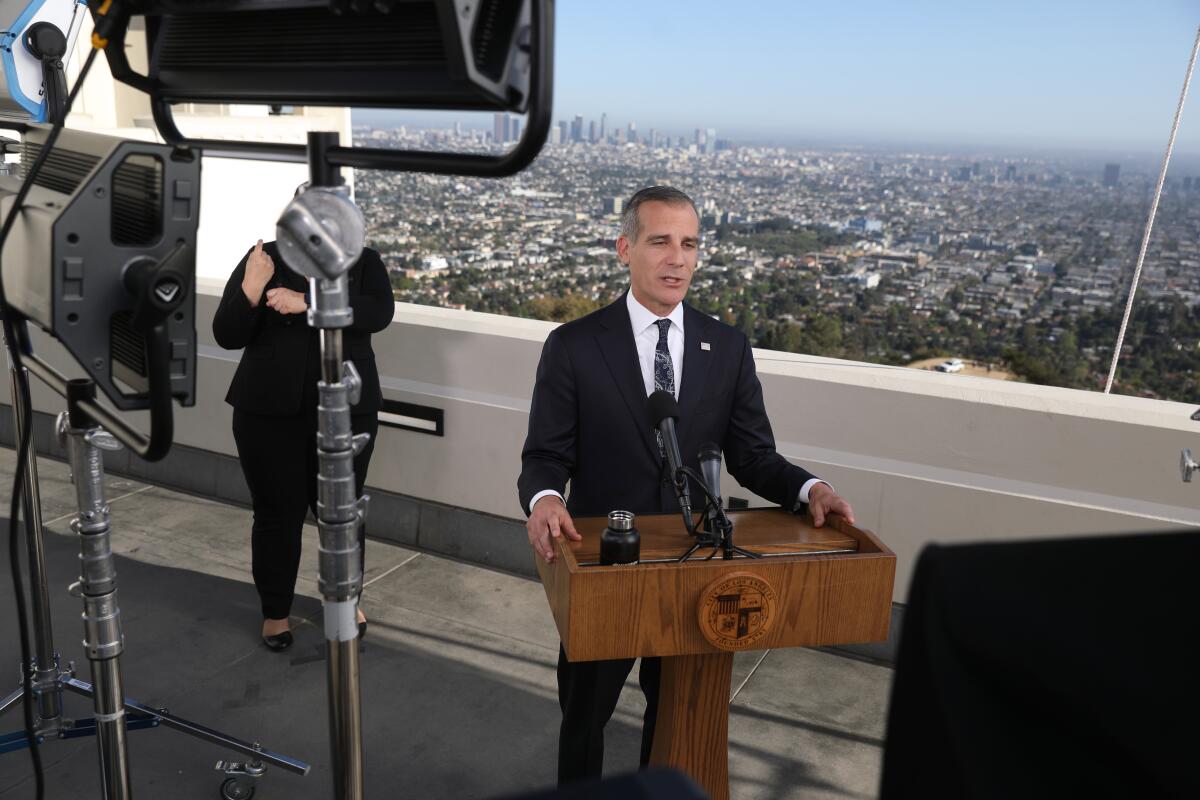

Most importantly, the judge zeroed in on Garcetti’s promise — announced Monday outside the Griffith Observatory — that the city would spend nearly $1 billion to address homelessness. Carter instructed the city to put $1 billion in an escrow account “forthwith,” and show that each source of the funds is “accounted for” within seven days.

Garcetti, appearing in North Hollywood Thursday at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the opening of a tiny-home village for homeless residents, said the city would have “a very, very strong case” if it decides to file an appeal. Los Angeles County officials have already chosen that path.

Beyond that, Garcetti said, the judge’s order will set up new bureaucratic barriers just as the city is getting momentum with Proposition HHH. More than a third of the nearly $1 billion planned by Garcetti would come from Proposition HHH, which would finance development and construction of 89 permanent housing projects during the next fiscal year.

The proposals reflect the shift that has taken place at City Hall since last year, when Angelenos filled the streets to protest police brutality and racial inequality.

Officials expect at least 56 HHH projects to be under construction on July 1, when the new fiscal year starts.

“We see this as actually adding friction and slowing things down, not necessarily helping things out,” Garcetti said.

The city’s HHH developers were even more unsettled.

Ed Holder, vice president of real estate development for Mercy Housing California, said he worries that the judge’s decision to take control of the mayor’s homelessness money — and his sharp criticism of the HHH program overall — could result in developers pushing back their construction schedules or failing to meet their financial obligations.

Mercy Housing is looking to start construction in July on a 92-unit project in L.A.’s skid row area. The San Francisco-based nonprofit group spent nearly three years assembling city, county and state funds and locking down a private loan — and has placed a huge order for factory-built apartments.

“We have over $2 million of our own money invested in this project,” he said. “I’m very concerned that an injunction would freeze all the progress we have made.”

Stephanie Klasky-Gamer, president and chief executive of LA Family Housing, said she fears that Carter’s order could jeopardize 13 projects her nonprofit group is developing. Of those, seven would receive funding from Proposition HHH.

A federal judge’s order to move homeless people off skid row and into shelters or housing has been met with doubts from activists.

Klasky-Gamer said investors in her group’s projects have been calling her worried that Carter’s demands could imperil city funding for those developments.

“It’s beyond frustrating right now. I would say it’s frightening,” she said. “His solution is not repairing what’s broken. His solution is actually destroying what does work.”

The judge’s order represents the latest chapter in a yearlong legal battle waged against the city and county by the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights, a group of downtown business owners and residents. The group contends the city and county have badly mismanaged the region’s homeless crisis, wasted public money and violated the civil rights of those who live on the streets.

In his 110-page order, Carter took aim at the HHH program, which focused heavily on construction of permanent housing with accompanying services. He said the city and county had made a “deliberate, political choice” to pursue permanent housing at the expense of immediate shelter, despite knowing that “massive development delays were likely while people died in the streets.”

Antipoverty activists have expressed concern that the order, and its tight timeline for offering people in skid row housing or shelter, would cause the city to set up cheap and temporary facilities to comply with it while failing to solve the underlying problem.

But the Rev. Andy Bales, chief executive of the Union Rescue Mission on skid row, welcomed the judge’s decision, saying it could “end skid row as we know it.”

Carter has accurately assessed the deadly tradeoff that L.A. has made, Bales said, by focusing its HHH dollars so heavily on permanent housing. Those types of projects frequently cost more and take longer to construct than other forms of shelter, he said.

“Why would anybody want people to die on the streets while they’re slowly rolling out help for a few?” he asked.

Bales said the order could allow for swift construction of tiny homes, mobile homes or other housing that is less expensive than HHH projects. And he dismissed the idea that the city is incapable of putting up the money demanded by the judge.

“You can’t say one night, ‘Hey, I’ve got a billion dollars,’ and the next night when you’re asked to put a billion in escrow, you say, ‘I don’t have a billion.’”

Krekorian, who heads the council’s budget committee, disputed that assessment.

Judge David O. Carter ordered Tuesday the city and county of Los Angeles to offer shelter or housing to everyone living on skid row within 180 days.

Garcetti’s proposal for spending nearly $1 billion has not yet gone before the City Council for review and approval. Because the money will be spent during the fiscal year that starts July 1, it “doesn’t exist yet,” the councilman said.

In addition, much of the money to pay for Garcetti’s homeless initiatives will flow into city coffers gradually over the coming year, not all at once, city officials said.

For example, housing funds from President Biden’s American Rescue Plan have not yet arrived. State dollars for homelessness prevention are expected in late summer. And more than half the HHH funds that Garcetti plans to use won’t be available until after the city issues more bonds, most likely in the fall, officials said this week.

The federal government won’t reimburse the city for operating Project Homekey sites, or motels converted into housing, until after that money is spent locally. The same is true of the city’s “rapid rehousing” initiative, which moves people into private apartments.

“There’s a lot of basics of budgeting that aren’t reflected” in the judge’s demand, Krekorian said.

If Carter insists on getting the $1 billion immediately, city leaders would ultimately have to pull funds out of every other program, Garcetti said.

“We’d basically shut down most of our day-to-day operations,” the mayor said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.