Orange County Water District works to clean polluted groundwater from decades of manufacturing

Underneath Orange County is a hidden arterial highway that groundwater moves through before eventually finding its way into homes.

More than 70% of the water served in Orange County is from groundwater. But some has become contaminated from industrial manufacturing because harmful chemicals that weren’t properly disposed of seeped down into the ground.

“Any area with a large amount of industrial activity, especially when it comes to machining, metalworking or military purposes, all of which kind of play a role in Orange County’s history, used a pretty significant amount of chemicals back before their disposal was particularly well-regulated,” Chapman University chemistry professor Christopher Kim said. “Unfortunately, those historical industries and activities have this legacy effect of still causing contamination problems through today.”

The Orange County Water District is tasked with determining the extent of the pollution, and containing it before more drinking water wells need to be shut down and contaminants spread to the principal aquifer, which is directly pumped by production wells for drinking water.

It’s a difficult and painstaking job to calculate the scale of the contamination when the problem is underground.

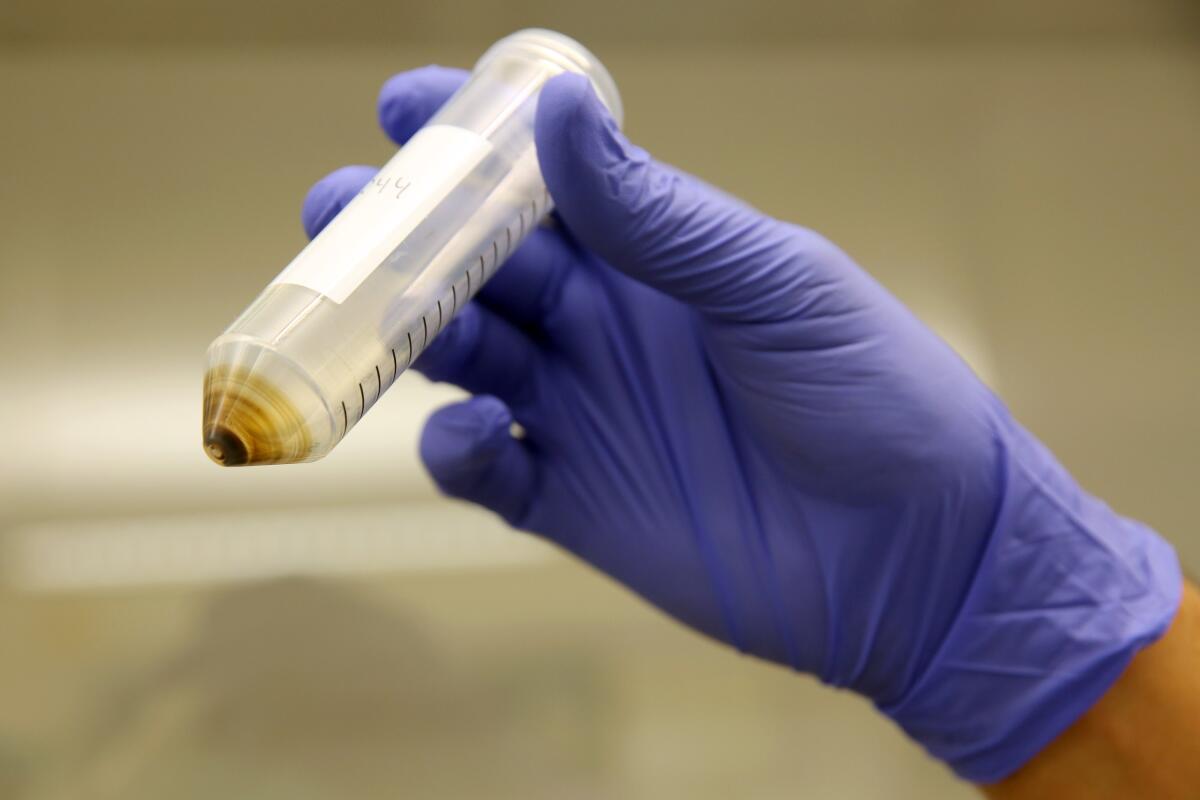

“Getting your arms around a large groundwater plume takes many years,” said Roy Herndon, chief hydrogeologist with the water district. “It’s a step-by-step process because everything is underground. You can’t see it. You have to do a lot of water well drilling and test boreholes where we collect water samples at different depths.”

The district is engaged in three major cleanup projects involving groundwater under the cities of Anaheim, Santa Ana, Fullerton, Tustin, Garden Grove, Orange, Villa Park, Yorba Linda, Irvine and Placentia.

Investigating cleanup of contaminated South Basin site

The district is conducting a feasibility study of a portion of the groundwater aquifer under Santa Ana, Irvine and Tustin that is contaminated from decades-old manufacturing.

The district completed a remedial investigation of the area and is evaluating the best way to address the cleanup.

“Now that we’ve kind of gotten our arms around the extent of it and the magnitude of it, it’s a matter of figuring out how best to clean it up,” Herndon said.

The contaminated plume extends about 2½ miles long and about a mile and a half wide in the South Basin. These are called co-mingled plumes, or separate releases of contamination that have entered the groundwater and mixed to form a large area of contamination.

Herndon said they are considering all the fundamental options of cleanup, which includes groundwater extraction, chemical injection, biological treatment and physical barriers.

“There’s a lot of different options to address groundwater contamination,” Herndon said. “But again, of those we look at ones that are most suitable for the conditions that are out there in terms of the width of the plume, the location of it and the depth of it.

“Then we narrow down the large list into a smaller list of what appear to be the most viable technologies. So that’s what’s being done right now, as they screen out what technologies appear to be less suitable or viable for this particular situation.”

Herndon said one of the options that will probably be retained is groundwater pumping, where contaminated water is taken out of the ground, treated and then put back in the ground.

The water would go back into the aquifer, where it eventually would find its way to a drinking water well.

Kim said the O.C. Water District runs the largest water purification system in the world.

“It’s a really challenging problem because groundwater is hard to get to. You can’t clean it like you can clean surface water, where you can just pump all the water easily at the surface or provide some sort of surface water treatment — just purify it with a bunch of bleach,” Kim said. “It’s down at depth, and you can only get to it with wells…. So, groundwater is extremely hard to treat and very expensive to treat.”

The district is aiming to have a draft of the feasibility study in October. The district will then provide time for fellow agencies and the Regional Water Quality Control Board to review and provide comments. The O.C. Water District will then begin developing a remedial action plan, which is a proposed plan to implement one of the strategies analyzed in the feasibility study.

The district first discovered the contamination of the South Basin in the early 2000s when contamination was detected in a drinking water well in Santa Ana.

Herndon said the district tests drinking water wells regularly for all varieties of chemicals. When contamination is detected, the well is shut down.

“No drinking water is being used in the area, or anywhere within Orange County Water District, that doesn’t meet drinking water standards,” Herndon said.

Kim said that testing of the wells is so extensive and frequent that any levels of contamination above regulatory limits are going to be caught and addressed before the water makes it into someone’s home.

“So, I think the risk is relatively low of it is accidentally not being noticed or getting into a position where it can cause risk or harm to humans,” Kim said. “But certainly just reducing the availability of that water through the closure of wells is going to have, no pun intended, downstream impacts on the population — in terms of the cost it takes the water district to manage and still provide sufficient water to meet demand, and the cost that they’re going to have to charge for that water.

“I think rather than being concerned about maybe toxic contaminants in your water, you could probably be more realistically concerned about your water bill, and your water rates, climbing as a result of these types of treatment costs.”

So far, only the Santa Ana well has been shut down. The district has detected trace levels in another well; the amount isn’t enough to shut the well down, but it does indicate that the contamination is finding its way down into the principal aquifer.

“The principal aquifer is definitely the one that we want to protect,” Herndon said.

Herndon said it can be frustrating at times how long it takes to understand the scale of the contamination and then come up with an appropriate cleanup strategy.

“The difficulty is trying to figure out where and how did the contamination get from the shallow aquifer into the principal aquifer,” Herndon said. “The sooner we can get a remedy in place, in terms of cleaning up the shallow aquifer then that will then take away the threat of how these contaminants are finding their way down into the principal.”

Herndon said it’s difficult to determine how the contaminants are getting into the principal aquifer, but some of the sources may be through old, abandoned wells.

This area of Orange County was used by farmers who irrigated their fields using agricultural wells, and in many cases, the wells were drilled before current standards dictating how wells should be constructed to prevent contamination. Herndon said the district doesn’t know exactly where the wells are — freeways and other structures may be covering them up.

“Unfortunately, a lot of these wells were probably not properly sealed when they were no longer needed,” Herndon said.

Herndon said that dating back to the 1950s, these areas in Irvine, Santa Ana and Tustin were industrial.

Businesses were working with metals and electronic circuit boards and used various chemicals like chlorinated solvents and degreasers. These chemicals could be stored underground and may have been improperly disposed.

The district filed a lawsuit against several companies. So far, more than a dozen businesses settled for a total of $28.5 million.

The remaining defendants in the suit include Soco West, Brenntag Pacific, GE Aviation and RadioShack, among others.

North Basin site makes the federal ‘Superfund’ list

The district is also conducting a feasibility study of a 5-square-mile portion of the aquifer underneath Anaheim, Fullerton and Placentia that is contaminated with volatile organic compounds from manufacturing in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s. Herndon said the feasibility study of the North Basin site is estimated to be completed in 2022.

Five water supply wells have already been shut down due to contamination, and others are threatened. The North Basin plume has spread further and deeper into the principal aquifer than the South Basin plume, Herndon said.

In September 2020, the site was added to the country’s Superfund list, which makes the site eligible for cleanup funds and other benefits.

The Environmental Protection Agency, which is overseeing the project, said the basin is a “critical water resource” that supplies drinking water for 2.4 million people in 22 cities.

“Superfund is good because it brings in federal authority that goes beyond even what state authority has in terms of getting parties who are responsible to implement and pay for cleanup, but it brings with it a bit of additional federal process that takes longer,” Herndon said.

Russell Detwiler, UC Irvine associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, said many sites of similar magnitude on the Superfund list still end up taking decades.

“That’s the cost of these things. It is easy to contaminate an aquifer. It’s very difficult to get it back to its pristine state,” Detwiler said.

Detwiler was brought in to provide expert testimony by a law firm of a defendant in the South Basin lawsuit. He said he didn’t end up being deposed or providing any on-the-record testimony.

Herndon said the district filed another lawsuit related to the North Basin site against more than a dozen companies. Raytheon and eight other businesses settled for a total of $21.4 million.

Northrop Grumman is the only remaining defendant in the case.

Widespread contamination closes drinking wells

More than 40 water wells were shut down after the O.C. Water District discovered widespread contamination from perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, which are found in consumer products like Scotchguard, flame-resistant materials, nonstick cooking surfaces and firefighting foam, among other products. The toxic chemicals, which are linked to cancer, have been found in water wells throughout California.

“We started to collect a lot of data, and we found these compounds in the aquifer,” Herndon said. “So it’s fairly extensive, covering a much larger area than the North Basin plume or the South Basin plume.”

Herndon said the water district is constructing wellhead treatment systems to remove and treat the compounds. The district is providing monthly updates on its PFAS-related efforts.

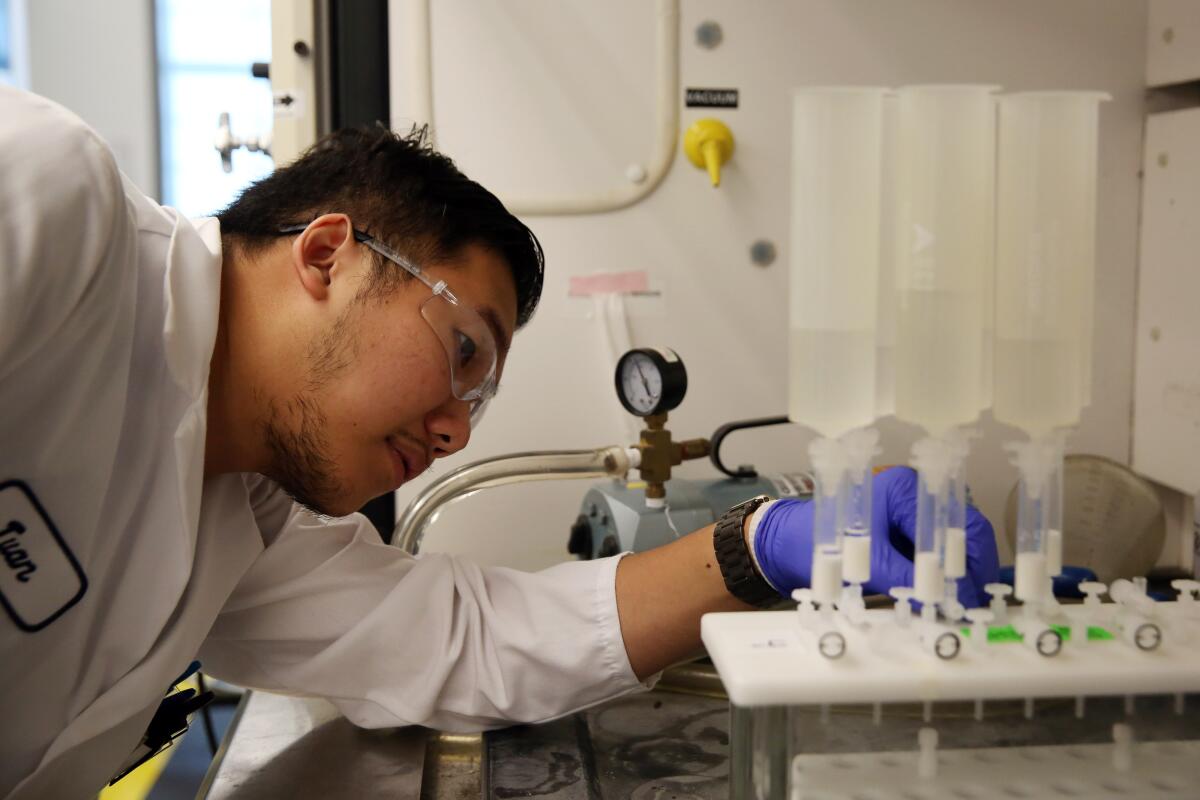

The water district’s Philip L. Anthony Water Quality Laboratory was the first public agency laboratory in California to attain state certification to analyze for PFAS in drinking water, according to the district.

The Orange County Water District, impacted cities and other local water districts filed a lawsuit in December against 3M, DuPont and other companies.

The lawsuit said that 3M and Dupont “are major chemical companies that manufactured PFOS and/or PFOA and knew or reasonably should have known that these harmful compounds would reach groundwater, pollute drinking water supplies, render drinking water unusable and unsafe, and threaten the public health and welfare.”

Herndon said the water district is not waiting for a settlement before implementing cleanup. He said Thursday there were no updates on the PFAS lawsuit.

“We are already moving forward with partnerships with the water provider agencies, the cities and other water providers to move ahead and put in treatment systems so that we can get the wells that have been shut down back online safely and provide high-quality drinking water that meets all regulations and standards,” Herndon said.

“The lawsuit will run in parallel with these actions, and certainly we hope that we can get some recovery from those responsible to help pay for all of this construction and future operation of these treatment systems so that the ratepayers don’t have to pay for all of it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.