Two jobs, full course loads, COVID-19 battles: CSU students persevere amid equity gaps

After a tumultuous year online and off-campus, students attending the nation’s largest four-year higher education system, the California State University, have persevered through the pandemic by largely maintaining their grades and course loads — although some troubling numbers point to the struggles of Latino and Black students, a Times survey has found.

Data provided to The Times by 18 of the system’s 23 campuses show that, on average, students’ unit loads and grades did not drop substantially in fall 2020 — the first full semester of online learning — compared with fall 2019.

In fact, average student GPA increased across the board, reflecting flexible grading and expanded withdrawal policies that were put into place during the pandemic, protecting students’ GPAs.

“Despite the enormous challenges, our students are, in large numbers, still pursuing their education. This speaks to their resiliency and determination,” said S. Terri Gomez, associate provost for student success, equity and innovation at Cal Poly Pomona.

But there were setbacks, too. Ten campuses reported year-over-year increases in withdrawals from classes, and 11 saw upticks in the percentage of students who received a grade of D, F or W, for withdrawal. The share of freshmen who continued from fall to spring term, an important element to their long-term success, dropped at 13 universities. And by some indications, Black, Latino and first-generation students fared the worst.

At Cal State Long Beach, the average GPA across all courses was 3.09 in fall 2019; jumped to 3.42 in spring 2020, when grading policies were most flexible; and fell to 3.26 in fall 2020, when traditional grading returned. The university typically receives about 5,300 requests to withdraw from classes each fall; last semester, it had 7,500 such requests, despite only a 3% increase in overall enrollment. Officials said this increase in withdrawals did not affect the number of students returning for spring or projected graduation rates.

At Cal State Northridge, where year-over-year enrollment was roughly steady, the number of withdrawal requests increased from 512 in fall 2019 to 650 last semester. By most other measures, though, students fared relatively well: Average GPA increased from 2.9 to almost 3.1, and average units earned increased from 12.4 to 12.6. The overall rate of students earning a D, F or U (for “unauthorized withdrawal,” which counts as an F) decreased. Gaps between low-income and underrepresented minority students and their more well-off peers did not widen.

In contrast, at Cal State Dominguez Hills, although the average GPA increased, so did the share of undergraduates on probation — from 3.4% to almost 5%. Grades of D, F or W accounted for 16% of all grades in fall 2020, compared with 14% in fall 2019.

The campus serves some of the most vulnerable students in the Cal State system: Three-quarters of its students are Black or Latino, and nearly the same share are the first in their families to pursue a bachelor’s degree.

And at Cal Poly Pomona, where the average GPA increased from 2.9 in fall 2019 to 3.1 a year later, withdrawals climbed from 797 to 1024, outpacing the university’s 6% enrollment increase. A bump up in the rate of D, F or W grades was attributed to increases in those grades among Black, Latino and first-generation students.

“We are seeing a disparate impact on students of color,” Gomez said. “All of these slight upticks in the data suggest a widening of equity gaps.”

For The Times’ analysis, Cal State East Bay and Cal State L.A. referred a reporter to online dashboards while others provided campus data directly. Cal State Bakersfield, California Maritime Academy, Cal State Sacramento, San Jose State and Cal State Stanislaus did not provide data. Cal State does not collect these data systemwide.

External pressures

Diana Alcantar, a junior at Cal Poly Pomona and the first in her family to attend college, took on a grueling pandemic routine during her fall 2020 semester: work, school, study, sleep. Repeat. No time for fun or to blow off steam — and no friends she could see safely.

Alcantar, who is majoring in liberal studies and lives with her mother and sister in Bellflower, became the household’s primary income earner during the pandemic. She worked 40 hours a week at TJ Maxx and Kumon tutoring to make up lost earnings from her mother’s nail salon job. As bills came due each month, she would grow anxious.

“It was so hard for me to focus and do my work … mainly because I was stressed or I was tired,” she said.

In the fall, Alcantar took Anne Cawley’s course on mathematical concepts for elementary school teachers. The class of 24 met on Zoom for two hours twice a week, and Cawley encouraged students to keep their cameras on.

Alcantar struggled to keep up with schoolwork. “I was kind of shy to talk to [Cawley] about what was going on,” she said. “Once I saw that my grade was going down, I reached out.”

Cawley met with Alcantar individually every Wednesday for an hour — and Alcantar finished with a B, helping to land her a spot on the dean’s list.

“If I hadn’t asked Dr. Anne for help, I wouldn’t have passed her class,” she said.

Alcantar tested positive for the coronavirus in December and spent her 21st birthday in isolation.

A week before the spring semester started, her grandfather died in Mexico — of COVID-19, her family believes.

Her experience is not unique. In surveys conducted by Cal State student government, faculty, administrators and outside research groups, as well as in correspondence with professors and interviews, students have described high levels of stress over their finances, as well as anxiety about contracting or spreading COVID-19 to family members and grief over lost loved ones.

Martha Escobar teaches Chicano and Chicana studies at Cal State Northridge, which serves a large working-class Latino population and many “Dreamer” students without permanent legal status. Of 27 students in her class who answered a survey about how they had been affected by the pandemic, 22 said they lost work or pay and/or took on new jobs to help their families make ends meet.

Escobar restructured her class — giving students specific graded readings rather than calling on them randomly, assigning a final essay with a prompt in advance instead of an in-class exam, and weighing discussion posts more heavily in students’ grades — making it difficult to fail.

“To be honest, I’m not as interested in the academics right now,” she said. “We’re in a global pandemic — they can always catch up…. I’m concerned about, how are they coping with all of this? How are they affected?”

Virtual difficulties

Faculty and students said they believed the grades earned by students in the fall reflected their learning but also noted that instructors’ compassion and course adjustments played a role. Some expressed skepticism that students had mastered course content to the extent they ordinarily would.

Mónica Palomo, a professor of civil engineering at Cal Poly Pomona, completely redesigned her lab course on water quality. Instead of collecting samples, running experiments and collecting data of their own, students analyzed existing data sets.

“The hands-on learning with chemicals was not there,” Palomo said. “I changed the learning objective to be more like an experience in consulting where they are given a bunch of data … and they need to make sense of it.”

She had at least 95% attendance and a high rate of participation.

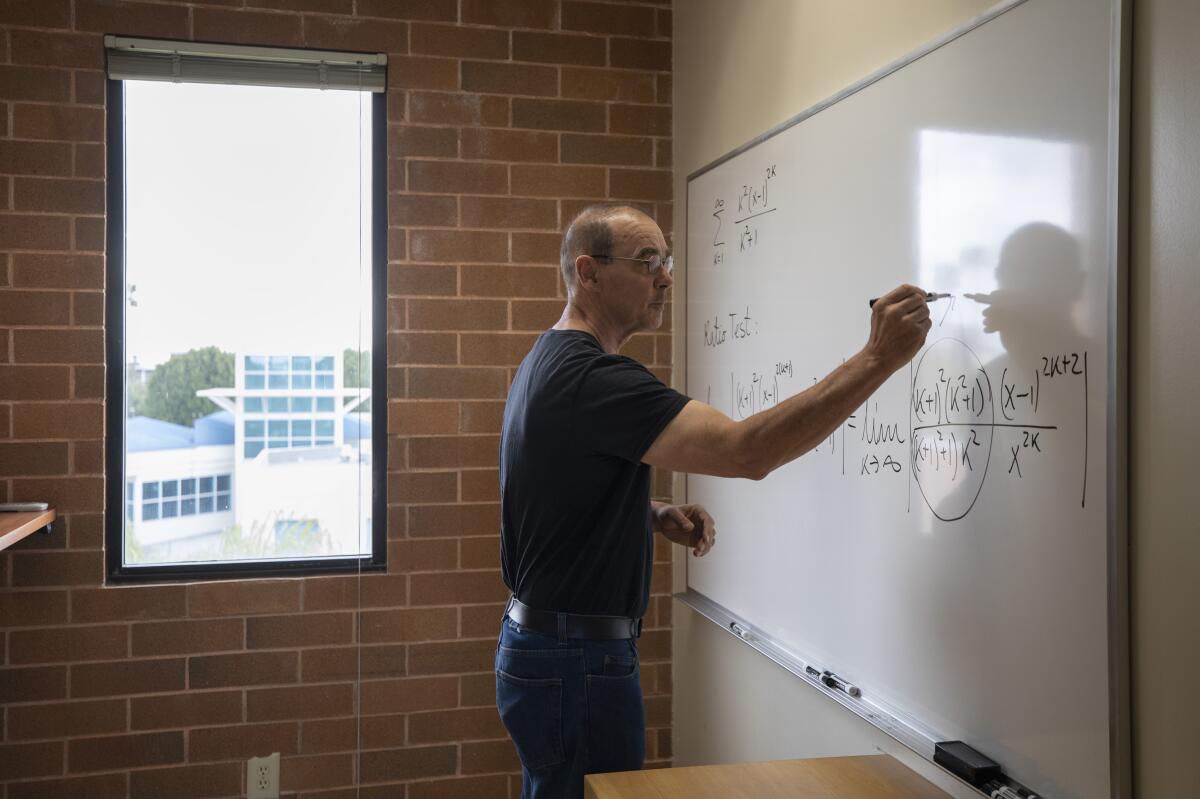

Michael Neubauer, a math professor at Cal State Northridge, has had online teaching experiences on both ends of the spectrum. Last semester, while teaching a “math ideas” course taught mostly though small-group and project-based work, he had high engagement, got to know his 25 students and was able to tell how well they were learning.

But this semester, in calculus II, which follows a more rigid curriculum and is taught largely through lecture, hardly any students turn on their cameras or ask questions.

In-person, Neubauer would chat with his students, getting a sense of their interests and progress. With a walk around the classroom and a glance at their papers, he could spot whether they understood how to solve a sample problem. On Zoom, he has no idea.

“I wouldn’t know these students if they walked by me on the street,” Neubauer said.

Rebecca Cohen, an engineering student in Neubauer’s calculus class, said it’s “intimidating … to be the only one in a room full of blank screens to ask a question.”

Cohen said Neubauer is still “one of the best professors I’ve ever had,” but she also relies on online videos and math software to learn on her own. “That’s what online school is — teaching yourself,” Cohen said. “And what you can’t figure out, Google will tell you.” She currently has a B.

1st-year experience

The stakes of virtual learning were perhaps highest for freshmen and first-generation college students, who are among those at greatest risk of dropping out.

Debbi Mercado, who teaches a freshman seminar at Cal State Northridge, said students were disheartened about missing high school graduation and their first semester of college, and they often talked about their hopes for “a real college experience.”

“I often marveled and was really touched by their good attitudes and their resilience,” Mercado said.

Kayla Fuentes, a freshman majoring in film production at Cal State Northridge, took mostly general-education requirements last semester and earned all A’s but said she would have learned better in person. In English class, she wished she could have sat alongside her professor for feedback.

“I wanted her to scribble all over my paper and give me all the suggestions I needed to write a good paper,” she said.

Instead, they met on Zoom and shared screens — a cumbersome process that left Fuentes unsatisfied. “There are holes in my learning,” she said.

Sabrina Ruvalcaba, a freshman studying political science at Northridge, hopes to work in the future at a university or community-based organization helping first-generation Latino students graduate from college. During the pandemic she picked up a second and, at one point, third fast-food job to help her family pay bills.

Early last semester, Ruvalcaba fell behind in an Africana studies class and decided to drop it rather than risk failing. In other classes, she relied on YouTube math videos, Instagram and peers. Pressed for time, she prioritized content she knew would be tested rather than absorbing all of the material.

It was a lot of pressure, and Ruvalcaba missed her friends and being involved with clubs at school.

“There were days when I was crying,” she said. “I really miss having someone where I could just talk to them in person and they could listen.”

Still, dropping more classes or leaving school wasn’t an option. Her mom and high school teachers and counselors had drilled into her that she would attend college and graduate.

“This is just going to be a bump on the road,” she said. “At the end of the day I still want my degree. I still want to continue my education so I can end up working on policies that affect students like me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.