USC survivors say $1.1 billion in settlements is justice for sex abuse ignored

Some were born in China, some in the San Fernando Valley. Some started at USC as the Berlin Wall fell, some were there when Donald Trump was campaigning for president.

They were white, Black, Latina and Asian. They were straight, gay, lesbian and bisexual. After USC, they became doctors, stay-at-home mothers, law enforcement officials, professors, accountants and lawyers.

What united them is a sorority of shared trauma in harrowing experiences in the exam rooms of the university’s student health clinic.

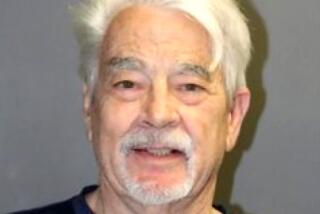

On Thursday, USC announced that it would provide these former patients of gynecologist Dr. George Tyndall a total of more than $1.1 billion in compensation, the largest sex abuse payout in the history of American higher education.

“I started shaking, I started crying,” said Brennan Heil, a 2019 graduate, of learning the news from an alert on her phone. “It’s like an indescribable feeling ... the fact that this is over ... that they have agreed, ‘Yes, we did something wrong.’”

Heil was among the final 710 accusers who settled lawsuits in Los Angeles Superior Court on Thursday for a total of $852 million, the largest share of USC’s overall settlement commitment. The women’s complaints spanned 1989 to 2016. About 50 others reached a previous deal for an undisclosed sum. An estimated 16,000 additional former patients were covered by a $215-million federal class action lawsuit inked in 2018.

Tyndall was the sole full-time gynecologist at USC’s campus clinic for 27 years. For many in that generation of young women, he was their first gynecologist and they had little understanding of how his questions and physical exams deviated from the norm.

One such patient was Audry Nafziger, a USC law student who visited the clinic in 1990. Nafziger recalled Thursday that she found it odd on that day three decades ago when the gynecologist locked his exam room door, took out a camera and began photographing her.

“But what did I know?” Nafziger, now a sex crimes prosecutor at the Ventura County district attorney’s office, recalled at a media briefing. “When he told me disgusting stories about oral sex with women in the Phillipines when I was in stirrups on the table, naked, I knew — this wasn’t right.”

Nafziger said Tyndall told her she had tested positive for a sexually transmitted disease, but years later, when she retrieved her medical records knowing she might one day pursue charges, she saw she had actually tested negative.

“This completely changed my life,” said Nafziger, one of those who settled her lawsuit Thursday.

Some colleagues suspected Tyndall was targeting women from other countries, especially USC’s growing contingent of Asian students. Outside medical consultants hired by USC in 2016 to investigate Tyndall’s medical practices bolstered those concerns. The firm’s report, made public during the litigation, concluded that many patients were vulnerable because of their age or language skills, and may not recognize harassment or file a complaint.

“It would be easy for a healthcare provider to take advantage of this,” the report by MD Review stated, adding that the gynecologist showed signs of “underlying psychopathy.”

For nearly 30 years, the University of Southern California’s student health clinic had one full-time gynecologist: Dr.

Those findings came too late for women such as Lucy Chi. Enrolled in a master’s program in 2012, she visited Tyndall for an exam during which she said he sexually assaulted her. She ran from the room and out of the clinic with employees staring after her.

“They all knew what happened. It was very obvious to me in hindsight that this was an open secret at the clinic,” Chi said in an interview.

In the years that followed, she said, she had flashbacks every few weeks.

“Random things remind me of him. It affected my relationship with men in general. I stopped trusting men,” she said. When her kind and mild-mannered husband raised his voice even slightly, she said, “I’d find myself afraid.”

Allison Rowland met Tyndall as a USC graduate student in 1993. She recalled the “slowly dawning horror of being trapped in a room with her feet in stirrups” and remembered Tyndall becoming angry at her for objecting to how he was conducting his gynecological exam.

“He pretended everything he was doing was normal and necessary,” Rowland, now a public policy analyst, recalled at the media briefing. When she brought her concerns to USC’s clinic staff, she said she was told: “Oh no, he’s a good doctor.”

Nicole Haynes was a junior and an accomplished track athlete in 1995 when food poisoning forced her to go to the clinic. Tyndall told Haynes, who had never had sexual intercourse before, to disrobe, and he proceeded to perform a pelvic exam.

“I was already in tremendous pain in my stomach — and I had never been penetrated before. It was a traumatic experience,” she said in an interview. The memory remained tucked away until 2018, when she read news about Tyndall and a “lightbulb went off,” she said.

After filing a lawsuit against USC, Haynes testified twice before lawmakers in Sacramento and met fellow victims, including a recent USC graduate.

“I don’t know if she was born when Dr. Tyndall abused me,” Haynes said, taking stock of the breadth of harm.

Tyndall has pleaded not guilty to dozens of sexual assault charges and is awaiting trial.

The exact amount each of the 710 women will receive has not yet been determined, although the settlement comes out to an average of $1.2 million per person. The ultimate payment will be determined by a retired judge who will allocate on the basis of each woman’s claims and experiences.

Haynes said she had not considered much of what to do with whatever payout comes her way, except that she’ll spend it on her mother, who has Alzheimer’s disease. “I did tell my dad, I wanted to get an electric chair for her — so she doesn’t have to walk down the stairs.”

Among the youngest to sue was Heil, now 23. She encountered Tyndall in 2016, her freshman year and his last before being forced out of the clinic, when she went to the student health center in the wake of a sexual assault. Heil wanted tests for pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. What she got, she said, was crude comments and inappropriate touching.

Heil was one of 15 former patients questioned under oath during the civil litigation about her experience with Tyndall. The deposition in October lasted an entire day, and the endless queries by a university attorney were unnerving, she said.

“It was literally like being told again and again that you were lying about something,” Heil recalled.

She said that she is buoyed by changes she has seen at USC, including the hiring of female gynecologists, and the settlement, adding: “I think I will finally be able to return to campus without having a panic attack.”

Some of Tyndall’s patients were not placated by the money. One woman who said she was victimized by Tyndall as an undergraduate and graduate student in the 1990s and early 2000s, noted that the school has yet to release the findings of an internal investigation conducted by a law firm.

“The financial accountability is there, but what I don’t understand is ... who are they protecting now?” said the woman, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

She also said USC should sever all remaining ties with former President C.L. Max Nikias, who was ousted in the scandal’s fallout.

“A lot of this stems from the culture he created,” the woman said. “To keep him on as an emeritus and legacy trustee is insulting. Remove him.”

Times staff writers Harriet Ryan, Matt Hamilton and Paul Pringle contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.