Column: A deranged white man aiming his bullets at Asians: The urgent lesson of 1989 Stockton massacre

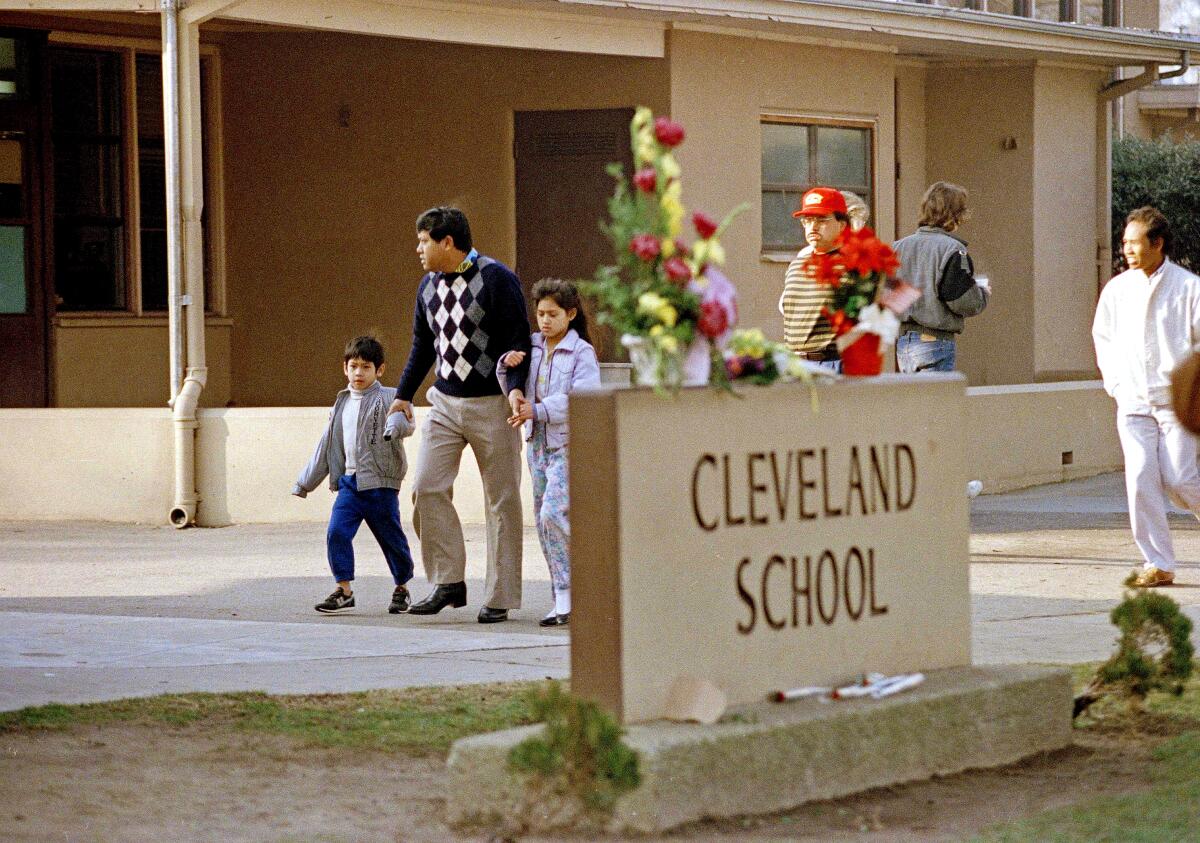

The playground at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton buzzed with the joy of recess on Jan. 17, 1989, as second-grader Sam Leam waited his turn for tether ball. It was a sunny winter day, near noontime, and Leam and his fellow classmates tried to get in some last-minute fun before heading back to their studies.

Suddenly, there was a sound. Firecrackers? A well-bounced dodgeball?

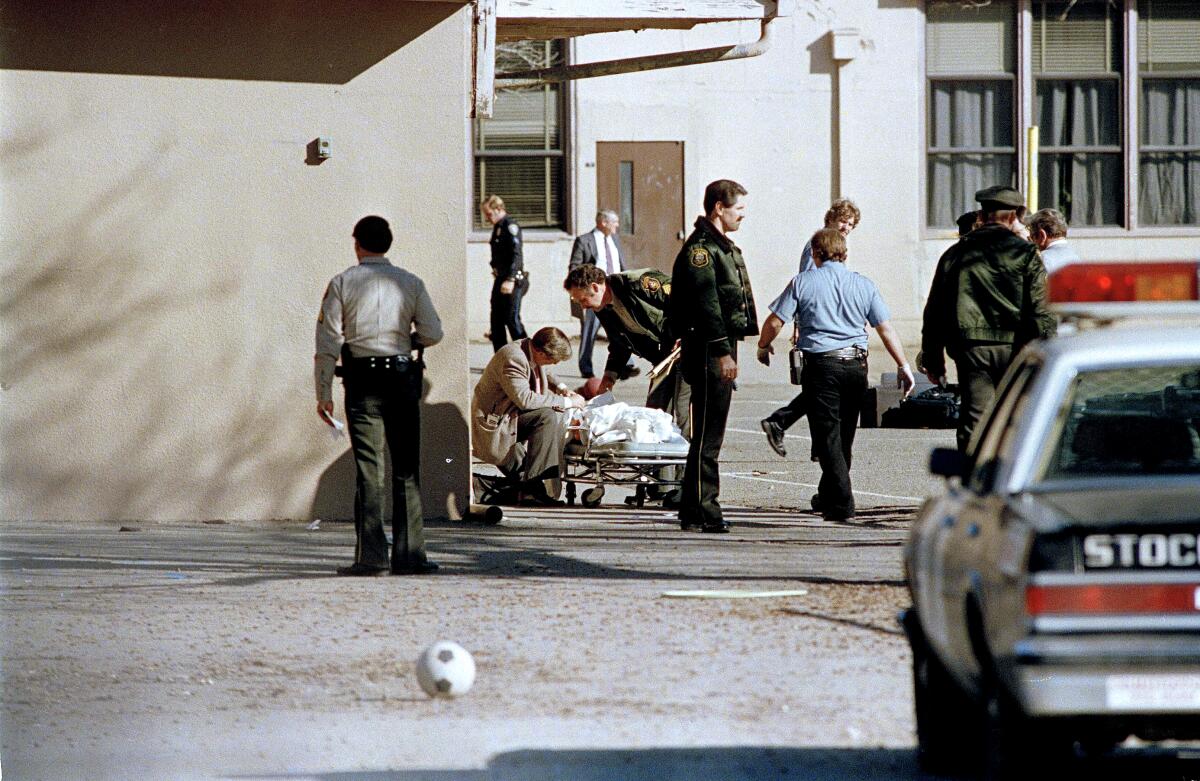

It was Patrick Purdy firing off rounds from a semiautomatic rifle. At them.

Students tried to run to safety but were gunned down by Purdy’s ceaseless sprays. He shot the 7-year-old Leam three times, but he miraculously survived. The now-39-year-old remembered “crawling on the floor in the hallway” trying to open doors, until a teacher scooped him up and saved his life.

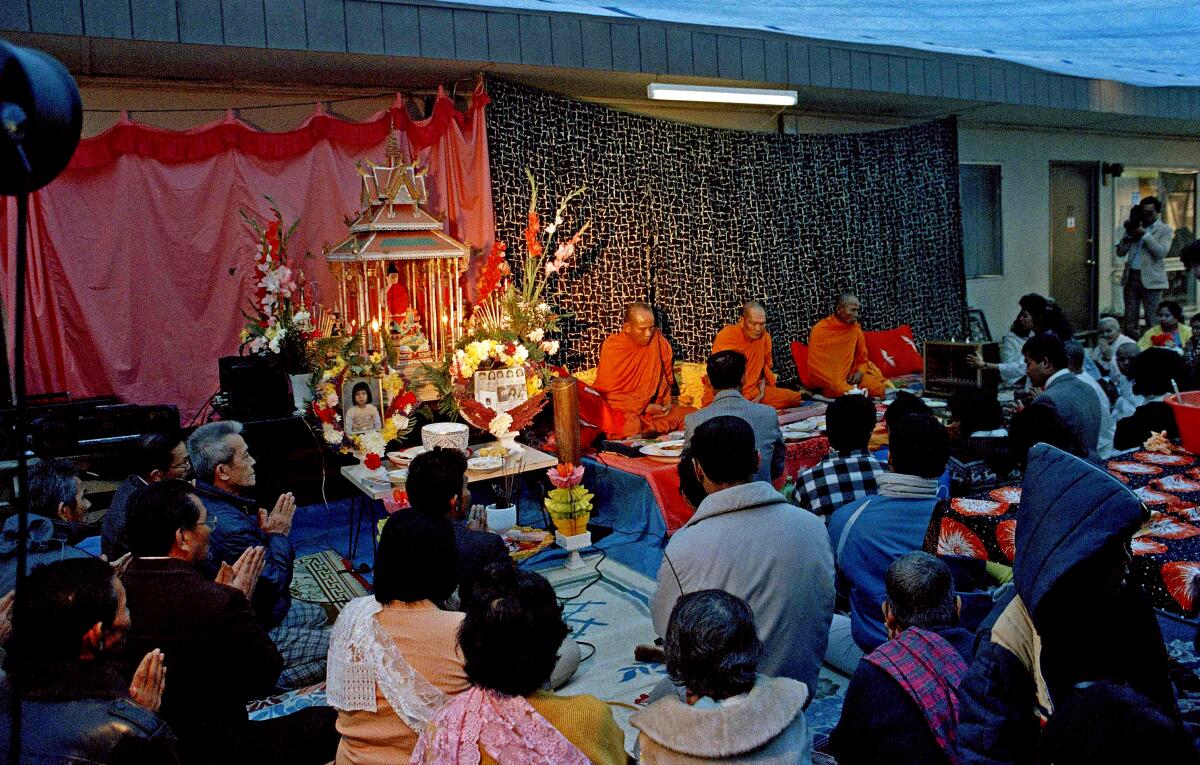

Purdy murdered five children — 6-year-olds Sokhim An and Thuy Tran, 8-year-olds Oeun Lim and Ram Chun, and 9-year-old Rathanar Or — and wounded 29 others before killing himself. “That day is imprinted on my head,” said Leam, who’s a real estate agent in Chicago. “It’s a part of me. It changed everything.”

His mind went back to that terrible day 32 years ago, after hearing the news that Robert Aaron Long had been accused by authorities of killing eight people around the Atlanta area on Tuesday, six of the victims Asian women.

The similarities between the 1989 Stockton massacre and the 2021 Atlanta-area rampage are chilling. Then and now, a deranged white man aimed his bullets at Asians. Then and now, law enforcement quickly discounted the possibility that race may have played a role in the killings despite the dead before them.

Then and now, initial media accounts reported the ethnicity of victims as incidental instead of intentional. Activists in each case — worried about an increase in anti-Asian attacks — immediately pushed back and demanded that skeptical government officials investigate. Community members united in the face of hate and vowed, “Never again.”

The Cleveland School slayings also hold a disturbing lesson that we hopefully don’t repeat in the aftermath of Atlanta: the sin of forgetting.

The political fallout focused on gun control, not anti-Asian violence, despite then-California Atty. Gen. John Van de Kamp declaring that an inquiry by his office found “festering hatred” pushed Purdy to target Southeast Asian immigrants.

Survivors hold an annual ceremony in honor of the victims, but no one besides locals seems to care. Nationally, some activists remember the bigotry of the butchery, but it never penetrated the American mind the way other race-based massacres have. That aspect didn’t even hit many of the Stockton survivors until much later.

“My family had the mentality of ‘We’ve gone through it, just move through it. Just like the war,’” said Sinath Vann, a community services officer with the Stockton Police Department who was a second-grader at Cleveland School when Purdy unleashed his rampage but escaped uninjured.

“You’re told a crazy man killed kids, and that’s it,” Leam said. “You don’t give it much thought until you pay more attention.”

Judy Weldon, the teacher who rescued Leam, hadn’t even heard of Van de Kamp’s investigation until I told her about it.

“No one has ever said that to us,” said the 72-year-old. She’s a member of Cleveland School Remembers, a group dedicated to the memory of the tragedy and which advocates for social justice. “We were in the middle of the nightmare, we didn’t know what the investigations were. It’s only been in the last several years that we’ve been hearing little notes about ‘Yeah, that was definitely a hate crime.’”

All these decades later, the three share what they endured as a warning, in the hopes it never happens again — even as it does.

“What happened in Atlanta was a bunch of innocent bystanders going on with their random daily duties of life, and ended up being victims of this senseless act,” said Vann. “It was just like me going to school, and a person came onto campus and started to fire shots with his AK-47.”

“Racism isn’t going away in the United States,” said Weldon. “That’s the trauma of our country. We don’t ever seem to change that narrative. We don’t become better.”

I’m ashamed to admit I’m one of those people who didn’t become better.

I remember the Stockton bloodbath well. I was a fourth-grader in Anaheim at the time, and recall footage on Spanish-language news broadcasts of crying parents and children. Terror gripped my young mind then, and it’s still one of the first things I recall whenever this country experiences yet another school shooting.

It wasn’t until decades later that I learned that the Cleveland School had a large Cambodian and Vietnamese student body. And that one of the last things Purdy told a bystander, according to the Van de Kamp report, was that “the damn Hindus and boat people own everything.”

None of that stuck with me — indeed, the only reason why I’m writing this column is that a reader who appreciated my last one (about the historical legacy of anti-Asian crimes in California) asked why hadn’t I mentioned Stockton.

“Most people only think of it as a school shooting,” Leam said. “When I tell them the story, they’re surprised. Unfortunately, it’s just a reality of the world we live in. People just brush racism under the rug because it doesn’t affect them.”

Weldon thinks one of the reasons why the Cleveland School shooting didn’t register to most people as a hate crime then was because of anti-Asian sentiments in the wake of the Vietnam War. “Too many people saw these children only as boat people,” she said. “I remember friends of mine saying at the time that ‘those people cut in front of me at the grocery stores.’

“When the shooting happened, the city came together like never before,” Weldon continued. “But then everything fell back into place and life went on for those who didn’t suffer.”

Let’s make sure that doesn’t happen with Atlanta.

Leam, Vann and Weldon are all heartened by efforts of people — political and not, Asian and not — to ensure that anti-Asian hate doesn’t get ignored anymore.

“If people just listened more instead of just talking past each other, we wouldn’t have these race crimes,” Leam said. “I read a lot of these posts on social media that say the media creates racism. How can you say these things? It boggles my mind. If someone says they feel they’re a victim of racism, don’t talk past them and say it doesn’t exist.”

“The task is huge,” Weldon said. “It’s really never-ending because [racism] started hundreds of years ago. These things keeps coming in waves. But we have to stop them for hate crimes to go away.”

“People talk about, ‘Oh we have to stop these racist individuals,’” Vann said. “For me, it’s like, ‘Let’s look at how [Purdy or Long] became who he was.’ Within his circle, I bet you not everyone was racist. How can we step in and help prevent these things from happening?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.