‘I’m scared I won’t be believed’: Asians fight to have racist hate documented

Jeongyeon Lee was walking from her car to a McDonald’s in La Habra recently when she heard someone nearby say “China” or “chinita.” She turned around, confronting two men sitting in the parking lot.

Speaking in Spanish, they called her “chinita cochina,” which translates in English as dirty little Chinese girl.

“I told them, ‘I am not Chinese, I am Korean,’” and they responded with another racial slur, Lee said.

Lee, 49, who majored in Spanish in college, was shaken, and she thought about recent disturbing stories in the news about hate-motivated attacks against Asian Americans. She reported the March 11 incident in Orange County on a portal that Radio Korea, a Korean-language station in Los Angeles, had created the day before.

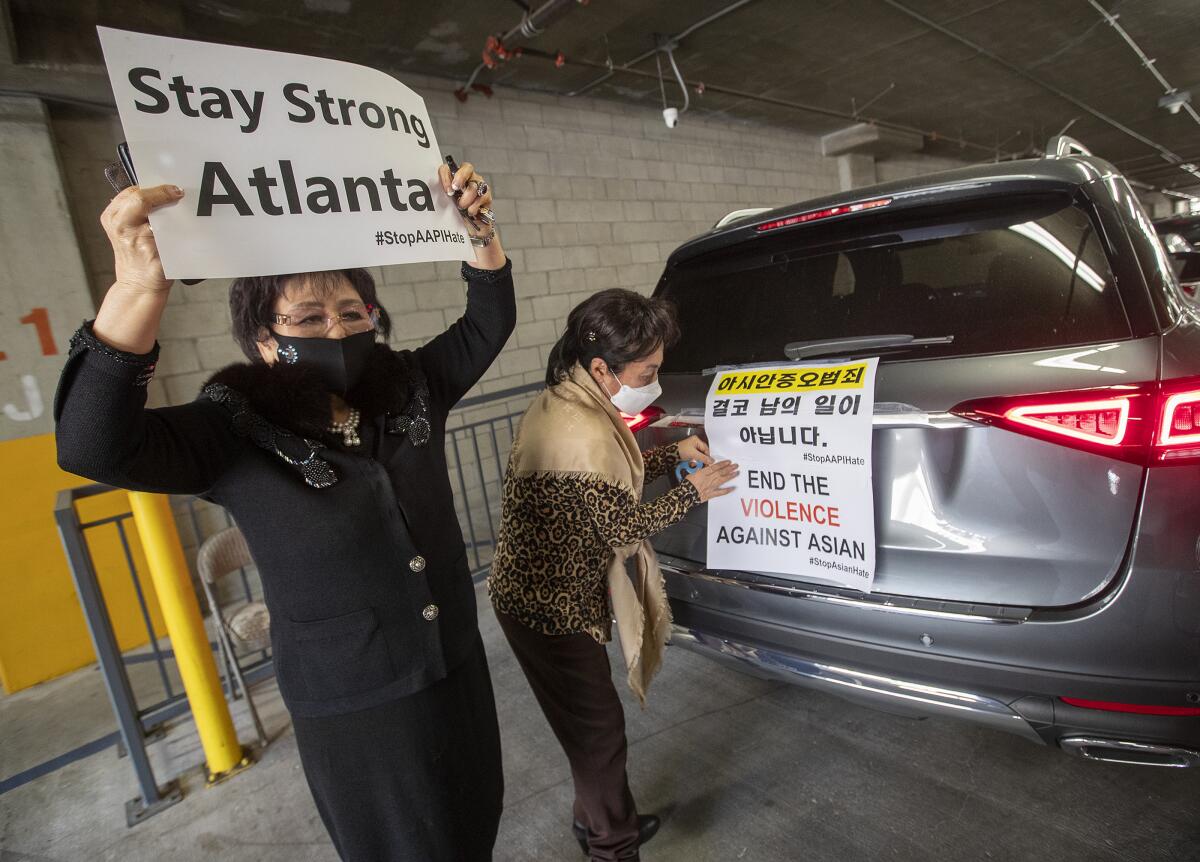

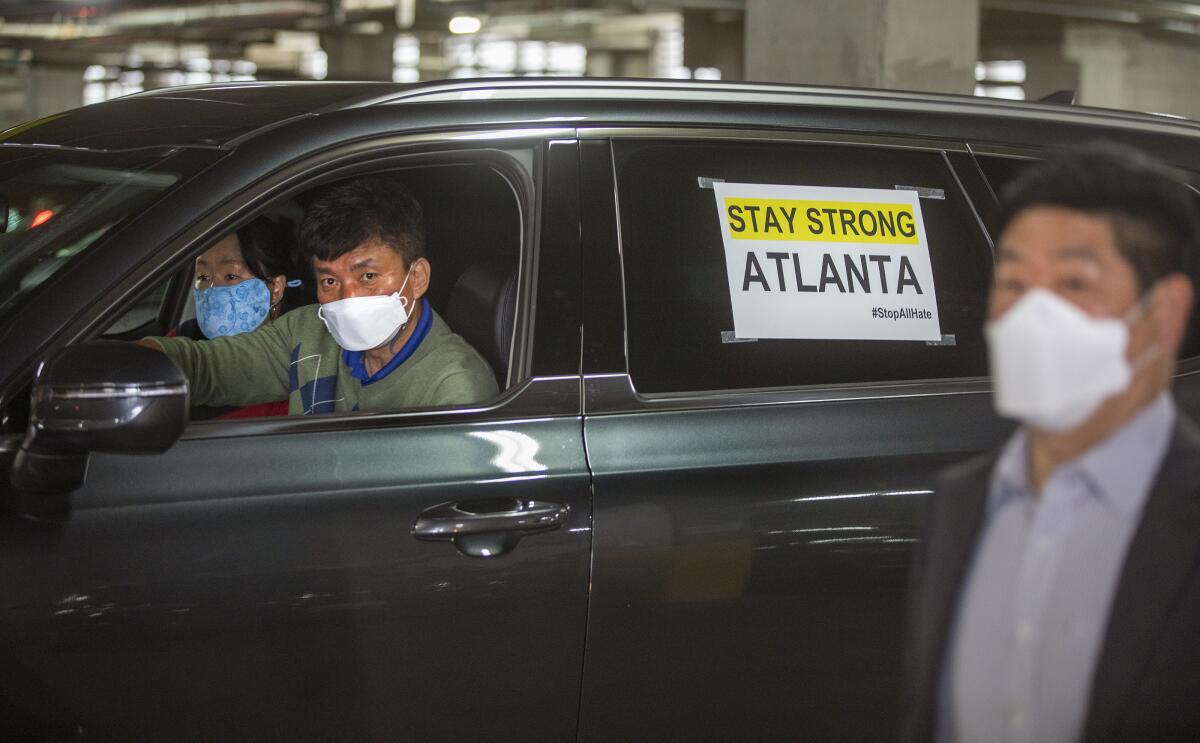

In the wake of Tuesday’s shootings at three Atlanta-area spas — leaving eight people dead, six of them Asian women — many advocates hope that the national focus on a rise in hate crimes and incidents against Asian Americans will empower more people to report their experiences and lead to better access to government resources for victims.

“Right now, we have to speak up,” Lee said. “I really think we have to get involved and elevate our voice and make this issue a big priority.”

Anti-Asian harassment and violence have surged across California since the beginning of the pandemic, often rooted in the misconception that the Asian American community is at fault for the global spread of the coronavirus. The virus was first identified in Wuhan, China.

In San Francisco this month, an assailant repeatedly struck a Filipino Chinese man in the face as he was heading back to his office from a lunch break in Chinatown — breaking bones and bruising his eyes. In Oakland in January, a man walked up behind a 91-year-old man in Chinatown and shoved him to the ground. Suspects have been arrested in both cases.

According to a report presented to the Los Angeles Police Commission in March, 15 anti-Asian hate crimes were reported in the city in 2020, compared with seven in 2019, marking a 114% increase. There were also nine hate “incidents” — encounters that don’t rise to the level of a crime — compared with seven in 2019, police said.

The day of the Atlanta rampage, the advocacy group Stop AAPI Hate released a report documenting nearly 4,000 racially motivated attacks against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders nationwide that had been reported during the pandemic.

Issues with data collection among law enforcement agencies have made it difficult to capture the full scope of hate crimes. A 2018 California state auditor report, for example, found that policing agencies had misidentified some hate crimes as hate incidents and weren’t conducting enough outreach to encourage the public to report potential crimes.

Connie Chung Joe, chief executive of Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles, named a variety of challenges that inhibit reporting, including language barriers, fear of retaliation, mistrust in the police, immigration status and shame for being humiliated.

“I’ve had people say to me that I’m scared to report it because I’m scared I won’t be believed,” she said. “Particularly for women, there’s a big fear of victim blaming.”

But advocates say that heightened attention to the issue may bring about changes, such as more people reporting and improved training for police officers to identify hate crimes.

Manjusha Kulkarni, a co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate and executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, said there needs to be more focus on building a social infrastructure to respond to hate incidents. Community members who experience attacks, she said, may want mental health services.

She’s also pushing for stronger civil rights laws and federal, local and state partnerships to track hate incidents that aren’t crimes.

Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at Cal State San Bernardino, said people should take advantage of the momentum by demanding that state legislators support an expansion of the groups covered under hate crime laws in certain states that offer less protection.

“When there’s a tragedy — and there’s enough of a groundswell of revulsion and failure of the law — it produces some possible results, but only if those of us who are concerned sustain the effort,” he said.

Community groups in L.A. and across the country are working to increase awareness of hate incidents and reporting. Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles is running social media campaigns to encourage people to report hate incidents to the organization and to offer bystander intervention training.

Chung Joe said advocates are also working with the LAPD to develop small resource cards in Korean, Chinese and Tagalog with information on mental health, housing and legal services for victims.

“When it’s a hate incident, sometimes the officers say there’s nothing we can do because it’s not a crime and we can’t arrest,” she said. “We want the community to feel they are getting something substantive from the officer.”

In the aftermath of the Atlanta shootings, LAPD Deputy Chief Blake Chow said the department contacted community groups to help translate a pamphlet on reporting hate crimes and incidents into Korean and other Asian languages. It has also increased patrols in areas of the city with heavy concentrations of Asian and Pacific Islander businesses, such as Koreatown and Chinatown.

Chow said the Los Angeles Police Department wants to know about hate incidents that don’t rise to the level of crimes so that it can have a better understanding of what’s happening in the community and refer victims to services.

Steve Kang, the director of external affairs for the Koreatown Youth and Community Center, said that since the shootings, he’s gone on Korean-language radio stations to encourage people to report hate incidents and to voice support for AB 557, a bill introduced in February whose sponsor hopes will create a statewide hotline for victims and witnesses to report hate crimes to the California Department of Justice.

“Instead of reporting to authorities or seeking assistance, we tend to keep it to ourselves,” he said. “I’ve been encouraging our community that that is no longer the status quo.”

Several years ago, he had kept silent himself. While perusing a mall in Brea with his wife, a woman randomly shouted at him in front of a Macy’s to “go back to China.”

“This is my country and I was flabbergasted,” he said. “I didn’t share it with anybody; I thought that was taboo. But now my mind has changed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.