Column: ‘It feels like a second-class shot.’ Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine equity problem

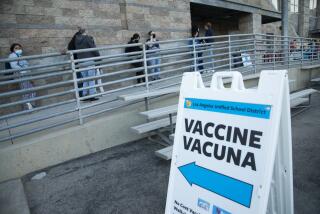

After weeks of being talked up and fawned over by public health officials, the new COVID-19 vaccine from Johnson & Johnson is finally starting to make an appearance in California.

In most quarters, this has been a cause for celebration. Doses that don’t have to be stored in freezers and can be administered in one shot instead of the two required for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines? No wonder I’ve heard several politicians call it a “game changer,” especially after so many months of supply shortages.

But in other quarters, the arrival of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has been treated more as a cause for concern — yet another reminder that having doses available and actually getting them into people’s arms in an equitable way are two very different challenges to overcome.

At issue are fears about the effectiveness the newest vaccine compared with offerings from Pfizer and Moderna, and suspicions that it will be sent primarily into poor Black and Latino neighborhoods where cases of COVID-19 have been the deadliest. (Both state and federal officials have insisted that they’re taking steps to ensure the latter doesn’t happen.)

“That they are going to put Johnson & Johnson in our communities really feels like a slap in the face,” said Corey Matthews, chief operating officer of Community Coalition. “It just doesn’t feel like it is the best shot. It feels like a second-class shot.”

Meanwhile, the messaging from public health officials has been consistent: Take whatever vaccine is offered. All three will save your life and prevent you from ending up in the hospital on a ventilator. The brand doesn’t matter and neither do the efficacy ratings. The vaccines are all safe and basically the same.

Matthews, who has been going door to door, booking appointments for people in South L.A. who otherwise probably wouldn’t know how to get vaccinated, is skeptical that such messaging will work on a population marginalized by systemic racism and distrustful of government institutions.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Persuading people to set aside their hesitancy and get immunized has required educating them about the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, Matthews said, and adding a new one to the mix could undermine progress. People “don’t know what Johnson & Johnson is,” he said, and so won’t get it.

Then there’s confusion over efficacy ratings. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine had a lower rating than the other two vaccines at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infections. But it’s also not that simple. All three vaccines were tested in different clinical trials in different conditions and never head-to-head, so a direct comparison of the sort everyone wants to make is actually impossible.

“You’re already talking about hard-to-access, hard-to-reach communities,” Matthews said. “And now we’re going to basically undercut the little bit of progress that we’ve made.”

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan was even more blunt when he initially turned down doses of the new vaccine for his constituents. “Johnson & Johnson is a very good vaccine. Moderna and Pfizer are the best,” he said. “And I am going to do everything I can to make sure the residents of the city of Detroit get the best.”

Many of those working on the front lines feel the same way about Los Angeles. But many others don’t see Johnson & Johnson as a lesser option, and instead see the debate over its rollout as a distraction from the far more important work of getting doses into arms.

I spoke with several elected officials, whose districts crisscross South Los Angeles, and they all downplayed such concerns or said they hadn’t heard anyone voice them. Mayor Eric Garcetti also defended the new vaccine during a recent Zoom event for Black Angelenos about COVID-19.

The state’s new volunteer page on its My Turn vaccination scheduling system streamlines the process for medical providers and general public to help.

“Johnson & Johnson — it’s not a secondary vaccination. It’s as good as the other two,” he said, seemingly in response to a question that no one had asked. “In fact, I know a lot of people just want to get one shot and be done because it’s 100% effective at keeping you from dying and being hospitalized. That’s clear.”

The dueling narratives — one based on fact, the other based on fear — illustrate what the White House has been trying to avoid since the Food and Drug Administration first authorized the Johnson & Johnson vaccine for emergency use in late February.

Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, who’s leading the Biden administration’s work on health equity and the coronavirus, said last week that all three of the vaccines will be distributed evenly and if certain vaccines consistently end up in certain communities, “we will be able to intervene.”

California’s Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly has said much the same, though it could prove somewhat more difficult to do, given that the rollout of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine happens to coincide with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s decision to reserve 40% of California’s supply of COVID-19 vaccines for the state’s poorest residents.

This doesn’t mean that the state will be flooding sites in Black and Latino neighborhoods with doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine — at least any more than it will be with doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. But, in the name of equity, it may look like it.

Hundreds of thousands of doses arrived in California this week. But a manufacturing issue could lead to smaller shipments next week.

Only 32% of Black adults say they would take a COVID-19 vaccine. That speaks volumes about the need for a reckoning on racism in healthcare and building trust in the communities hit hardest by the pandemic.

There’s also a logistical reason that poor neighborhoods should get more than their share of the new vaccine, given that it doesn’t need to be kept as cold and is therefore easier to administer door-to-door in neighborhoods where people don’t have cars or are otherwise homebound. The one-shot formula also is ideal for vaccinating essential workers with multiple jobs and little free time or for people who are homeless or otherwise difficult to track down for second doses.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine really can be a game changer. It has the potential to save a lot of lives. But getting Californians to take it means public health officials first need to get serious about nixing the narrative that it’s somehow second-class.

Just saying that all the vaccines are the same isn’t going to cut it — not after public health officials spent months touting the north-of-90% efficacy ratings for the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines as a way to persuade hesitant Americans to roll up their sleeves for the needle.

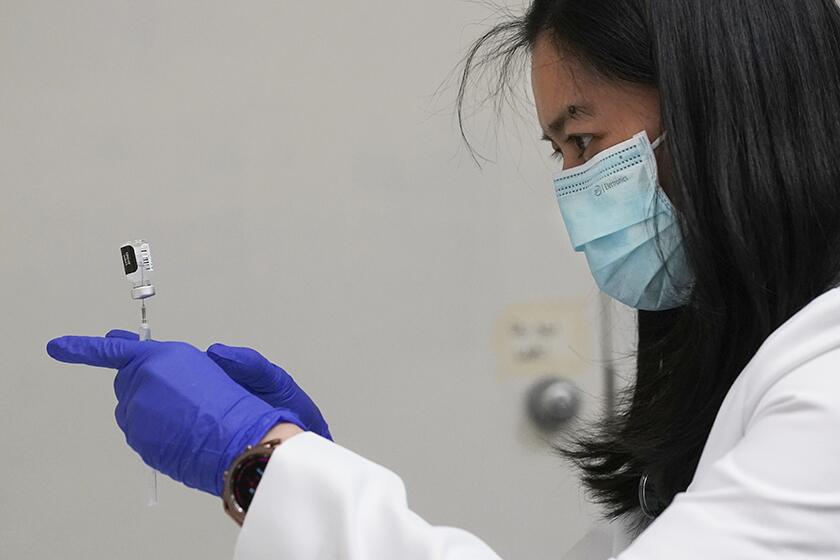

Nor does telling people not to pay attention to brands. This is America, after all. During my last stint as a volunteer at Kedren Community Health Center, which is now offering both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, I lost track of how many people requested a specific brand and wanted to argue when they were told no. Who knows what will happen when doses of Johnson & Johnson show up?

“Get the first vaccine that’s offered” is sound advice. But let’s not forget to explain why.

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.