Column: California’s vaccine distribution has been chaotic. It could get worse with Blue Shield

Getting a lucky break in both the crowd and the rain clouds, Howard Alonzo ducked under a blue tent and into a relatively short line at Jesse Owens Park on Wednesday afternoon. Hours earlier, hundreds of mostly Black and Latino Angelenos had been waiting there, hoping to get their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

“My family members all came like a couple of days ago and got vaccinated,” he said. “Then I got a text message from them.”

Indeed, to find this site — the newest in South Los Angeles — you pretty much have to know someone who knows someone. Forget about scouring government websites or scoring secret access codes to the state’s joke of an online appointment system, MyTurn. Personal referrals, paper fliers and Google Forms are the go-to tools here.

Well, for now anyway.

The timeline isn’t clear. But whenever Blue Shield of California begins fully managing the state’s disjointed system of distributing vaccines to counties, pharmacies and healthcare providers, everything could change. And that’s what Los Angeles County Supervisor Holly Mitchell fears most.

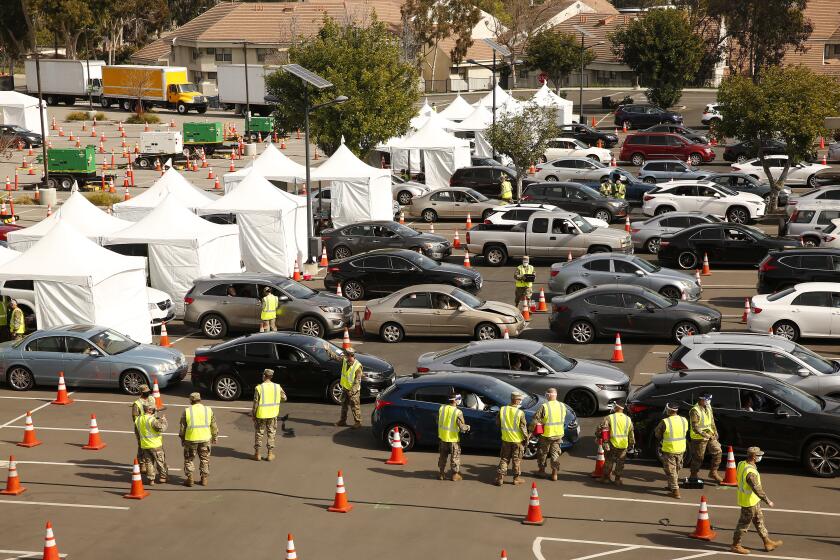

While the state’s rollout has been chaotic by any and every stretch of the imagination, community-based clinics and nonprofits, often with the help of local elected officials, have found creative ways to get doses into the arms of the most vulnerable Californians. The question now is whether all of that work to ensure equity will be upended.

State officials said the move is designed to both slow the spread of coronavirus and speed up the reopening of the economy.

“We’ve got a system that’s up and running. And so now we want to come in and kind of change the rules of engagement, reinvent the wheel?” said Mitchell, who worked with community groups and an alphabet soup of government agencies to open the vaccination site at Jesse Owens Park. “That’s not helpful.”

She’s not alone in her thinking either. Officials from the reddest to the bluest swaths of California share her concerns about the insurer acting as an overseer.

Undoubtedly, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s new vow to reserve 40% of the doses California receives for the millions of mostly Black and Latino residents of 400 low-income ZIP Codes will help temper that. But there still are many unknowns about our collective future under Blue Shield.

Will the insurance giant centralize the state’s vaccination distribution network, taking power from counties and perhaps consolidating it so there are fewer providers supplying smaller, community-based sites?

Will it put a new focus on standardization, forcing community health providers to use MyTurn whenever possible? Or worse, force them to ditch some of the flexibility they’ve had to make decisions on the fly, such as not requiring every single piece of state-mandated paperwork when it’s clear that someone qualifies for a vaccine as a caretaker?

And why is California putting an insurance company in charge of vaccinating millions of people who are uninsured anyway?

Adding to the worry is that very few people, from those on the ground distributing doses to those in elected office making policy, seem to have answers. Even Mitchell, who recently met with the president of Blue Shield of California, said she walked away discouraged and confused about the methodology the company is using in “putting together an algorithm to determine” how vaccines will be allocated across the state.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Last week, a spokesman with the California Department of Public Health told The Times that county health departments will mostly lose direct control of their supply of vaccines, and that the providers allowed to continue administering the shots will be selected by Blue Shield based on their ability to distribute doses quickly and equitably.

This week, a spokesman told me that Blue Shield will implement a distribution plan on behalf of the state and that the point isn’t to start from scratch. The insurer echoed that sentiment in a statement to The Times, saying that the state is responsible for determining eligibility and priority for vaccinations, and that vaccine allocations will be based on those criteria.

“Community based groups have already done a great deal of work and we will build upon that. We know that the equity work is hard work. It’s easy to do on paper, and is very difficult and takes a lot of attention and time and resources to do in practice,” Dr. Mark Ghaly, the state’s Health and Human Services secretary, said during a Thursday morning press briefing.

That means, he continued, “working to make sure that things like MyTurn don’t get in our way. That we use it as a tool to protect appointments and target appointments for the communities and that, ultimately, we achieve even higher levels of equity.”

In the meantime, state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) said that he and other members of the Legislative Black Caucus plan to meet with Newsom to try to understand why the state hired Blue Shield and how much the insurance company is charging.

“I think we should trust the county and the operators who can get the shots in arms,” he said, rather than an insurer.

Rare is the issue that can inspire solidarity between liberal urban and conservative rural California, but this is one of them.

Up north, officials in Lassen County said this week they are dreading the switch from their in-house vaccination appointment and distribution system to the one that will operate on Blue Shield’s algorithms. Mistrust is particularly high after a recent state-run COVID-19 testing program there turned into a “boondoggle,” said county administrator Richard Egan.

Blue Shield of California’s takeover of the state’s vaccine delivery system lack buy-in from counties, with none of California’s 58 counties having signed the Blue Shield contract yet.

“Our strategy is going to be to try to get as many people vaccinated as we possibly can before the state takes over the program because, frankly, we think it’s going to be problematic,” he said. “We don’t understand his notion of switching courses midstream, particularly in our county.”

In the Central Valley, officials in San Joaquin County told my colleague Anita Chabria that they’re worried Blue Shield will undermine existing efforts to vaccinate farmworkers. Specifically, Health Care Services Director Greg Diederich is afraid work that he’s done to assign risk scores to every resident, in hopes of vaccinating people based on their location and living conditions rather than age alone, will be abandoned.

While it’s unclear exactly what Blue Shield will do once it takes over, it’s clear what the insurer should do. And that is listen to those working on the ground and finding ways to achieve equity.

At Jesse Owens Park, Corey Matthews, the chief operating officer of Community Coalition, said the group had managed to book vaccination appointments for more than 1,200 people, mostly from South L.A., in less than two days. That’s a real feat in a county where residents of wealthy neighborhoods have higher vaccination rates than those in poor neighborhoods of Black and Latino essential workers who have been hit hard by COVID-19.

The problem isn’t the order in which people can book their appointments online. It’s the fact that people have to get online at all.

“Our main goal was just ensuring that we were very targeted and strategic in how we deployed the outreach,” Matthews said. “That way, the listing doesn’t go all over the place and then you have people coming from other parts of the county.”

Alonzo said he hadn’t even bothered trying to sign up anywhere else — especially not after his son’s mother had to drive all the way to Fontana to get vaccinated. Several others in line had similar stories of being discouraged by the vaccination maze.

“More red tape will not be tolerated,” L.A. City Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas said. “People who want to be vaccinated should not be discouraged in any way. After all, red tape could very well be seen as the enemy of equity.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.