California’s rainy season is starting about a month later than it did in the 1960s, researchers say

California’s annual rainy season is getting underway about 27 days later now than it did in the 1960s, according to new research. Instead of starting in November, the onset of the rains is now delayed until December, and the rain, when it comes, is being concentrated during January and February.

“The onset of the rainy season has been progressively delayed since the 1960s, and as a result the precipitation season has become shorter and sharper in California,” said Jelena Lukovic, the lead author of the study. Lukovic is a climate scientist at the University of Belgrade in Serbia.

Less rain is falling in the so-called shoulder seasons of autumn and spring, and more is falling during the core winter months.

The worst fires occur in the fall, rather than in the hottest summer months, because that’s when vegetation is at its maximum dryness.

In a state that just endured its worst wildfire season in history, this doesn’t come as good news. In California during 2020, about 4.3 million acres burned in nearly 10,000 fires, resulting in 33 fatalities, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire).

Researchers found that summer-like weather conditions were extending into October and November. The fall and winter seasons are also the time when strong, desiccating offshore winds develop in California.

“Santa Ana season is mainly October and November,” said Eric Boldt, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard. “By December we normally start to get winter storms that put an end to fire season as the fuels become too wet. However, some of our strongest Santa Anas can occur in December and January when winter storms are more powerful, and that is a problem if we have not received precipitation in advance of those stronger systems.”

In California’s Mediterranean climate, winter rains typically taper off and end in the spring. Grass and brush that sprout with the early season moisture dry out over a long, hot, generally dry period that extends beyond the autumn equinox in September. By November, though, rain usually arrives and wets down the landscape, dampening the fire danger.

Most years, the start of the rainy season would typically be neck and neck with the beginning in earnest of the offshore wind season. Climatologist Bill Patzert calls this the annual race between the rain and the Santa Ana winds.

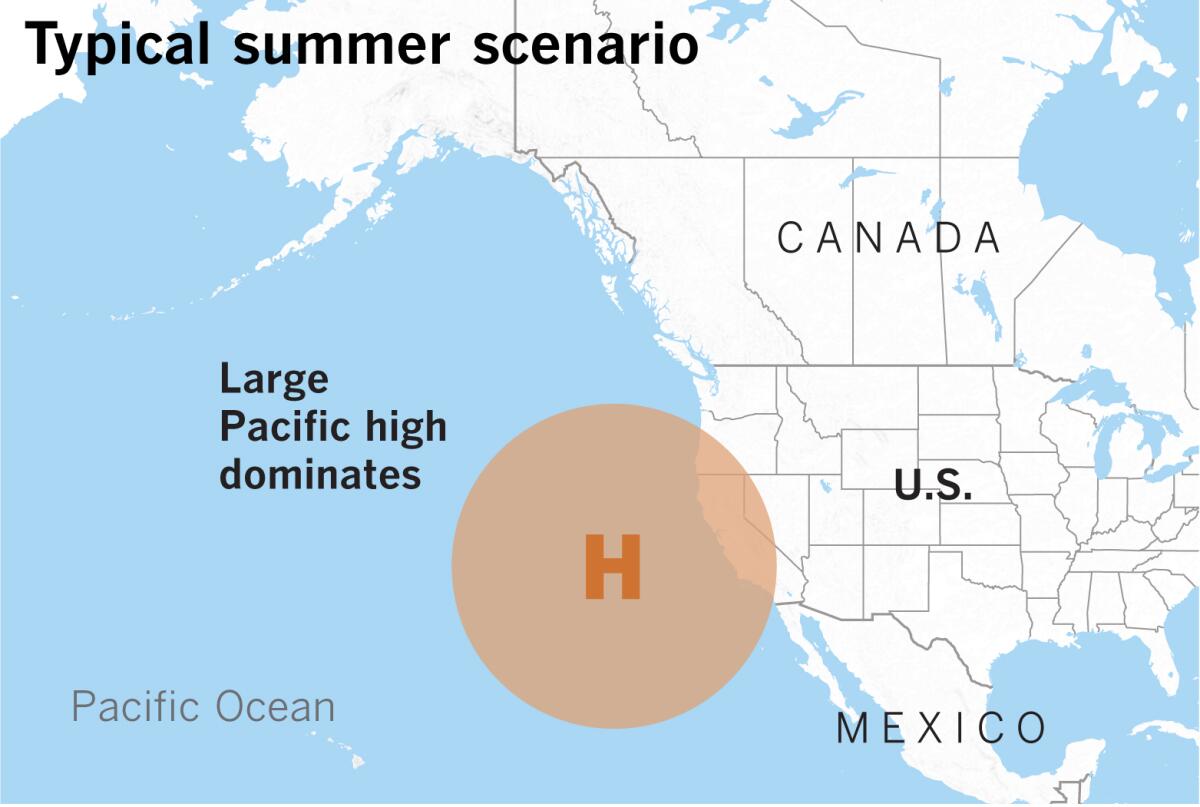

The strong offshore winds are a switch in the usual pattern. For much of the year, the prevailing winds in California are westerly, mainly coming from the west or northwest. That means cooler, moist breezes blowing off the Pacific Ocean toward land, pushing marine stratus clouds inland. There, what is called the marine layer usually moderates the sun’s potency during the months when the sun is at its seasonal highest point in the sky.

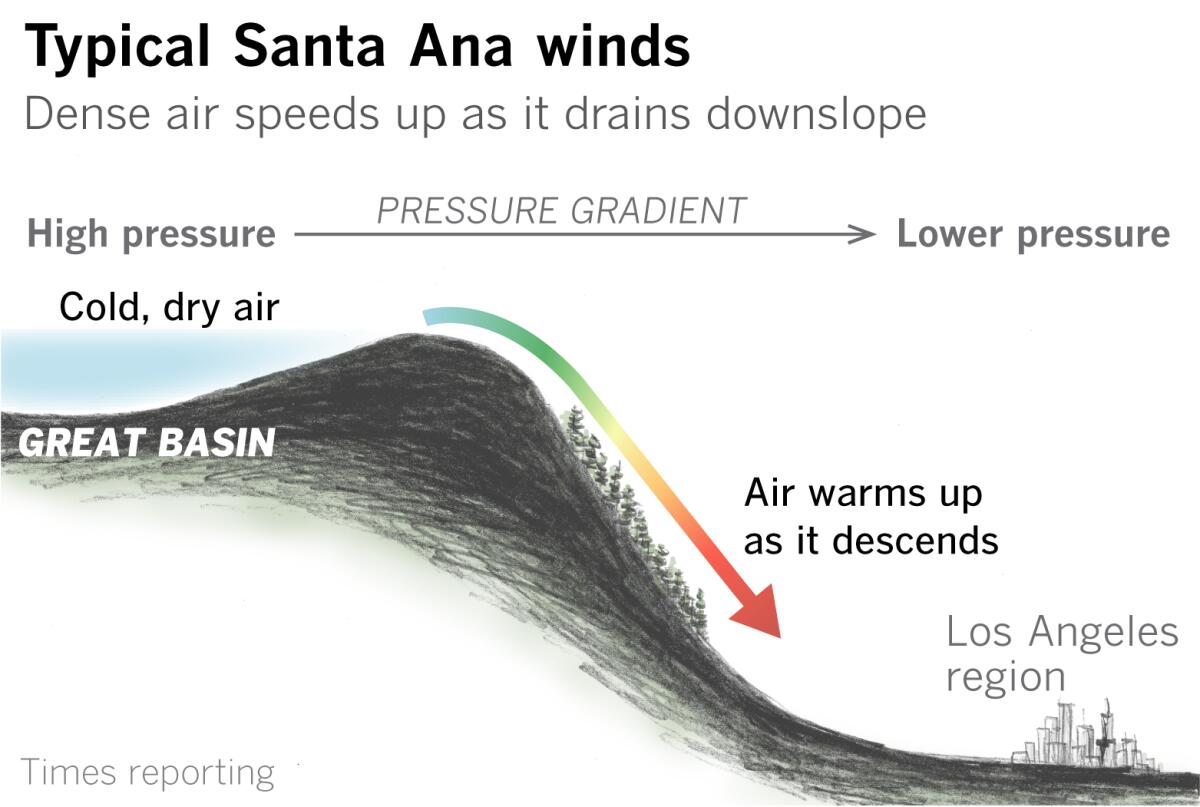

In the fall, the sun’s rays are weaker, and cold high pressure forms in the interior of the West, mainly over the Great Basin, promoting offshore winds in California. That is, winds that blow from the land toward the ocean. These winds heat up and dry out because they’re compressed as they move from higher interior elevations toward sea level. They scour cloud cover from the sky and can bring relative humidity down to the single digits.

The best known of these downslope winds are the aforementioned Santa Anas in Southern California and the Diablo winds in Northern California.

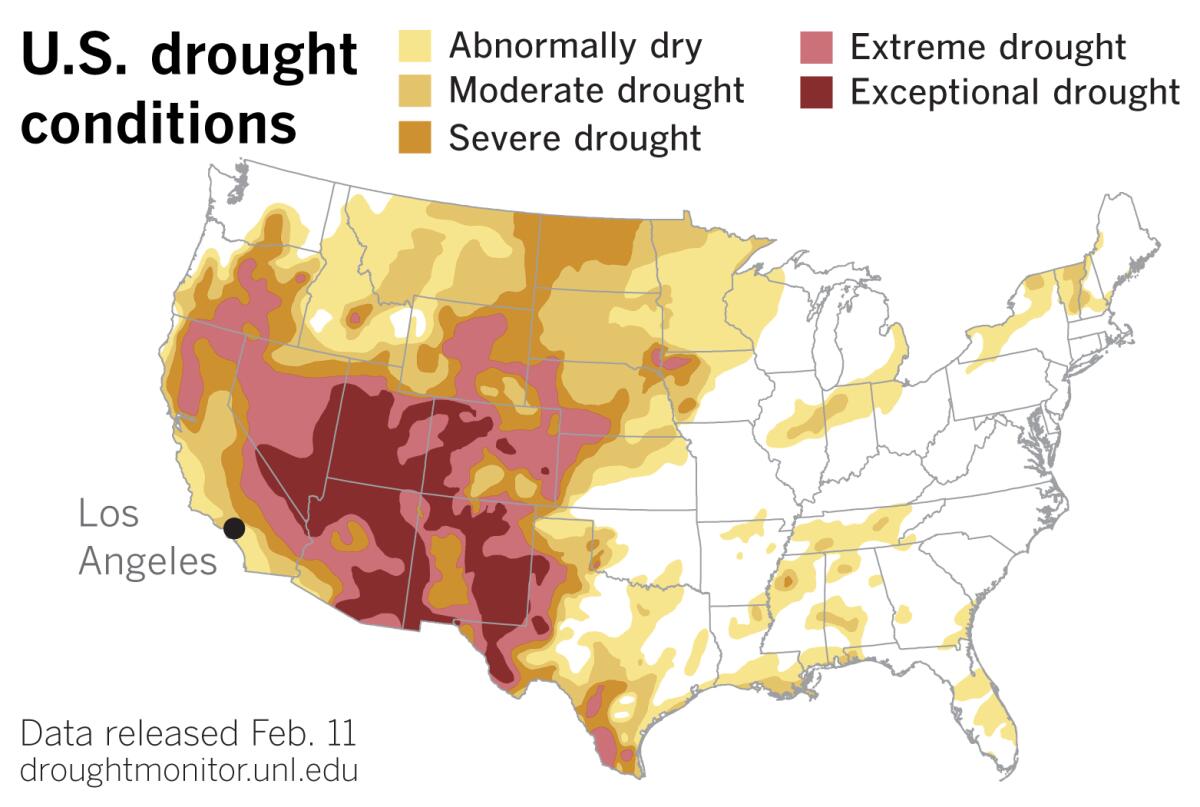

If the rains arrive a month later in California, as Lukovic, et al., have found, that means the rains aren’t competing with the Santa Ana winds anymore. The absence of shoulder-season rain gives the hot, dry winds an extra 27 days to drive every last drop of moisture out of an already dry California landscape.

“The longer into fall without any rain that you go, the fuels throughout California become critically dry,” said Jon Heggie, a battalion chief with Cal Fire. “These dry fuels combined with Santa Ana winds present the worst-case scenario each fall.”

Heggie likened brush that starts out moist after the previous winter’s rains, then dries out over the long summer and fall, to a sponge by your kitchen sink. When you leave on vacation, it’s moist and supple, but when you come back after a week or two, it’s dried out, shrunken and as stiff as a board.

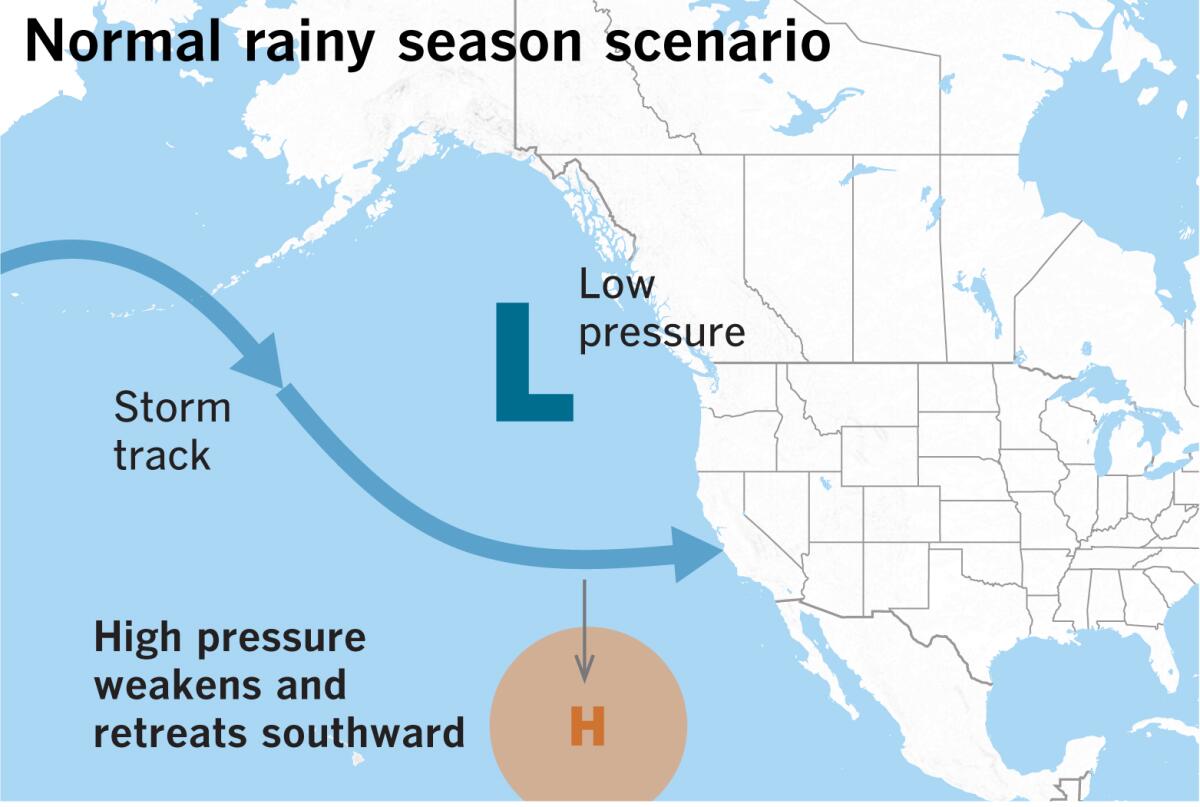

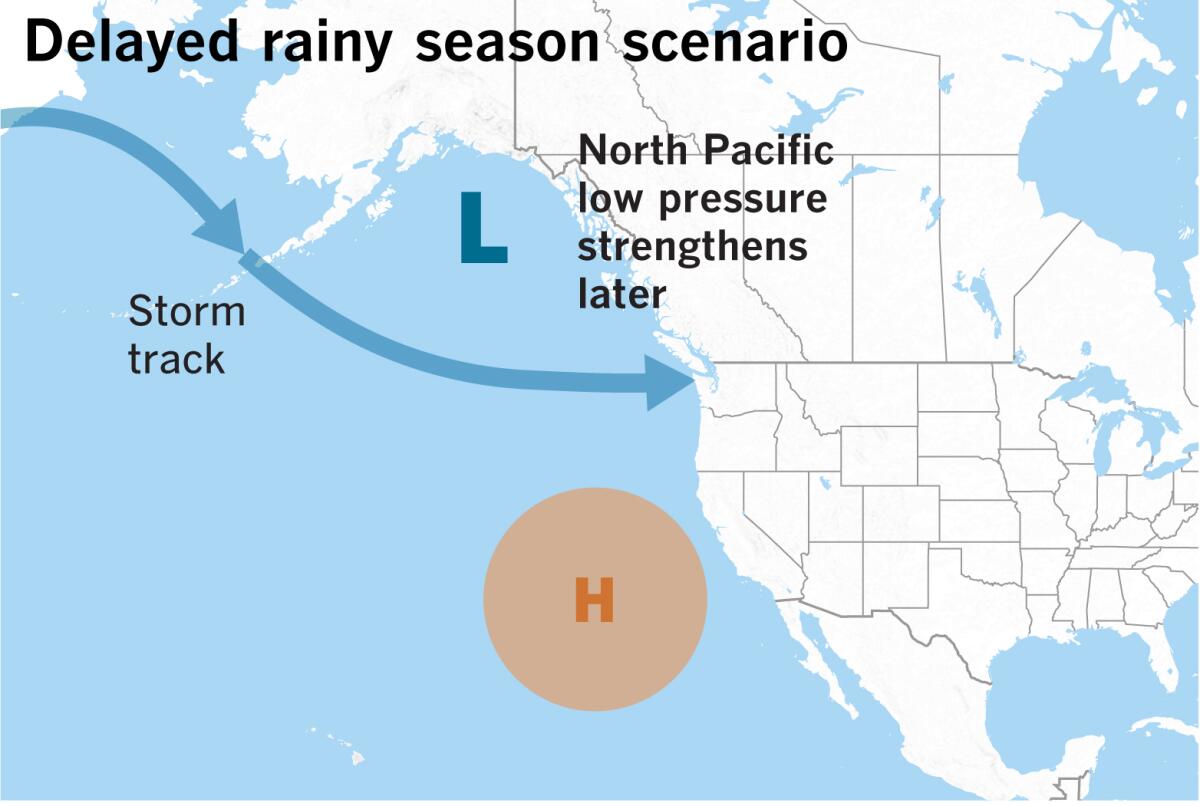

California’s dry summers and wet winters are products of predictable atmospheric patterns. In the summer, high pressure along the West Coast promotes onshore breezes and keeps rain away. With the winter season, the high pressure usually weakens as low pressure in the North Pacific strengthens, allowing the storm track to take aim at the state.

But according to John Chiang, one of the study’s authors, the trend toward a tardy rainfall onset is tied to later strengthening of this North Pacific low-pressure system. The researchers say this pattern change is bringing more rain to Pacific Northwest states such as Washington and Oregon, and less to California.

Researchers found that these shifts exacerbate droughts and wildfires. When the storm track does belatedly shift southward, the rainy season during the core winter months shows a “distinct sharpening.”

An elongated dry season that extends further into the fall, when the state is raked by fire-fanning offshore winds, followed by more intense rainfall during the core winter months, raises obvious concerns about mud and debris flows in burn scars.

A delay in the start of the rainy season that compresses rain and snowfall into core winter months also affects the way the State Water Project stores and releases water from reservoirs for shipment south to be used for agriculture and municipalities.

California agriculture has adapted and will probably continue to adapt to the seasonal aspects of rainfall.

“There are a plethora of papers coming out from modelers forgetting the fact that we are actually farming the desert,” said S. Kaan Kurtural, a specialist in the Department of Viticulture and Enology at UC Davis. “Our system is based on irrigated agriculture, not rain-fed systems. The scale and efficiency of production of permanent crops in California is probably one of the greatest success stories of this country.”

“Here in California, our institutions have been managed based on the climate of the 20th century,” Patzert said. “Going forward, with a warmer California and a later start to the rainy season, we will have to adapt and reorganize how we manage our civilization.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.