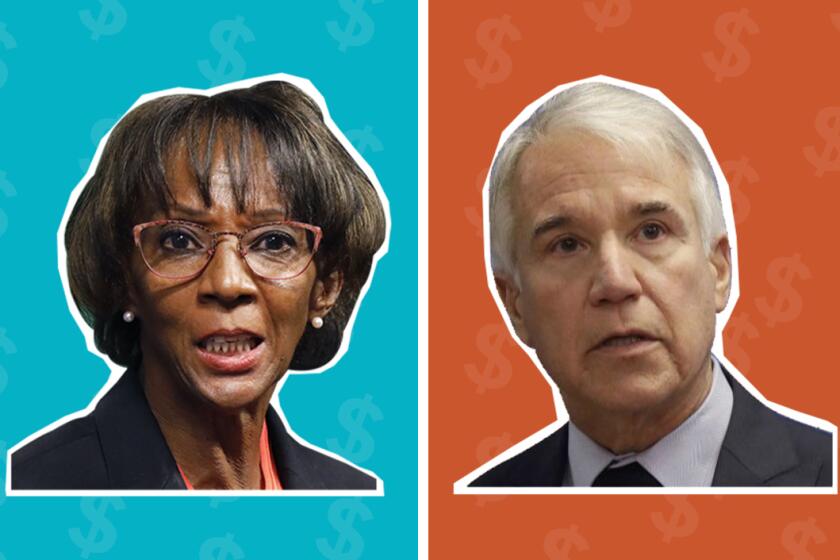

‘It’s a showdown’: California district attorneys battle over criminal justice reforms

Criminal justice reformers nationwide rejoiced when L.A. County voters chose George Gascón to lead the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office, celebrating a big win in a years-long campaign to replace traditional law-and-order district attorneys with ones intent on change.

And just hours after being sworn in, Gascón delivered to his backers: He announced a slew of policy directives that barred prosecutors from seeking the death penalty, trying juveniles as adults, attending parole hearings or filing most sentencing enhancements that can increase a defendants’ prison term.

Nearly as quickly, the news instigated a brawl among California’s public prosecutors, with the organization representing 57 out of the state’s 58 district attorneys questioning both the legality and wisdom of Gascón’s mandates. Now, many of the state’s old guard of district attorneys are openly sparring with reformer colleagues in a power struggle that could shape criminal justice in California and other states.

“It’s a showdown of exactly how much power one branch of government has to override other branches,” said Sacramento County Dist. Atty. Anne Marie Schubert, who opposes Gascón’s reforms as overreach thats ignore victims’ rights. “We are elected to enforce the law, not make the law.”

“We are moving exactly in the direction that the voters of California have asked us to move in,” countered Contra Costa County Dist. Atty. Diana Becton, who has been a force in progressive reforms. “We’ve done it the other way for a really, really long time.”

Although the movement to replace traditional district attorneys has gained momentum since the 2017 win of criminal defense attorney Larry Krasner as Philadelphia’s top prosecutor, the anger and protests unleashed by the death of George Floyd while in police custody hardened the battle lines in Los Angeles and helped propel Gascón to power. But his immediate orders weren’t well received by a staff that had questions for a boss it barely knows.

The union representing L.A. County line prosecutors — those who handle cases day to day — sued Gascón last year hoping to stall some of his changes. . Monday a judge ruled largely in their favor. The decision will almost certainly be appealed and could ultimately reach the state Supreme Court.

Becton believes if Gascón ultimately loses, it could have a “chilling effect” on the authority of public prosecutors to implement reforms and decide who will face a judge and how serious charges will be — even in places where line prosecutors don’t have the power of a union.

A push to back progressive district attorney candidates across the U.S. is forcing some law-and-order incumbents to embrace criminal justice reform

The California District Attorneys Assn., which is supposed to advocate for the state’s elected prosecutors, filed an amicus brief in support of the union. Dozens of progressive prosecutors around the country filed briefs in support of Gascón.

The divide comes as Gov. Gavin Newsom is considering a short list of names for the attorney general post that likely will soon be vacated by Xavier Becerra, whom President Biden has tapped to be Health and Human Services secretary. Newsom is reportedly considering two district attorneys with strong progressive credentials, Becton and Jeff Rosen from Santa Clara County. Others among many rumored contenders — House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg — are lawyers who have pushed police reforms.

“The next attorney general can have an enormous impact on the direction of criminal justice reform in California and nationwide,” said Rosen. “When the largest state moves in a certain direction, that has ramifications for the rest of the country.”

While Becerra often sidestepped criminal justice reforms, an attorney such as Becton, Rosen, Steinberg or Schiff could use the powerful office to embrace fast action. Most notably, the state Legislature recently passed a law allowing the attorney general to take over investigations of officer-involved shootings. Becerra largely left those cases in the hands of local prosecutors, offering reviews when asked.

But that alarms some in law enforcement: California recently modified the legal bar for when officers can use deadly force. Prosecutors in conservative counties rarely charge officers in such cases. Some worry that losing local control of those investigations to a progressive state prosecutor could mean more charges.

The reform movement is also changing the dynamics in local election cycles and in the state Capitol.

Law enforcement and prosecutors’ unions across California spent millions in a failed bid to defeat Gascón last year, and have reliably been some of the biggest donors in district attorneys’ races. But criminal justice political action committees, especially the Real Justice PAC, largely funded by billionaire George Soros, have spent millions in recent years leveling the playing field by funding candidates like Philadelphia’s Krasner and Gascón. The PACs are also pushing prosecutors to refuse law enforcement donations to avoid a perceived conflict of interest.

Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Oakland), another contender for attorney general, has discussed legislation to preclude district attorneys from investigating officer misconduct if they accept law enforcement contributions.

At the same time, old-guard prosecutors and their law enforcement allies have found their voices less heeded in Sacramento. Instead, a breakaway group of prosecutors that includes Gascón, Becton, San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin and San Joaquin County Dist. Atty. Tori Verber Salazar have gained influence, forming a separate advocacy group last year, the Prosecutors Alliance of California.

Cristine Soto DeBerry, the group’s executive director, said the alliance was created in response to “minority rule” taking hold in the California District Attorneys Assn. Collectively, the breakaway prosecutors head some of the most populous and influential district attorney’s offices in California — on average, L.A. County alone files roughly one-third of all felony cases in the state.

State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena), who has been an author of multiple police reform bills, said that the California District Attorneys Assn. still holds “tremendous sway” within the Capitol, but “in the 10 years I have been here, we do see a shift.”

“Even some of our Republican colleagues are at least open to discussion,” he said.

Some district attorneys with CDAA said they are not opposed to reform — and have enacted many in recent years — but object to what they describe as Gascón’s heavy-handed approach. Even Rosen, the Santa Clara County district attorney whose office is considered one of the most progressive in the state, cautioned against unilateral orders.

“How reforms are implemented determines the success of those reforms,” said Rosen. “Leading doesn’t mean dictating.”

Supporters of Gascón point out that progressive prosecutors across the country have used their power to make similar radical shifts, beginning with what is known by progressives as the “Krasner memo” in 2018, considered revolutionary for its use of prosecutorial power to enact reforms in Philadelphia.

El Dorado County Dist. Atty. Vern Pierson, who serves as president of the CDAA, pointed out that nearly every county in California has made some reforms on issues including cash bail and how nonviolent crimes are prosecuted. But, he said, elected district attorneys have a duty to prosecute criminals based on the specific circumstances of each case.

“It’s as though in L.A. ... they’ve lost sight that there are people who are dangerous and they do belong in prison,” Pierson said. “At some point this is more about politics, and maybe it really comes down to identity politics more than anything else.”

Boudin, the San Francisco district attorney, said although more traditional prosecutors have branded progressives as not caring about public safety, he believes groups like the CDAA have chosen policies that favor punishment over data-driven solutions.

“The devastation of losing a loved one in a violent way is not something to be minimized. But that does not mean the best outcome is the harshest possible penalty,” he said.

The fracture between traditionalists and progressives has led at least two conventional district attorneys to seemingly attempt to take cases from colleagues recently.

San Diego County Dist. Atty. Summer Stephan sought to reclaim jurisdiction over several counts related to a defendant charged in a deadly 2019 string of crimes, fearing Gascón would be too lenient on the defendant. Stephan, who left the Republican Party in 2019 and identifies as an independent, said she’s enacted reforms including diversion programs for nonviolent offenders. But she thinks people like Gascón are oversimplifying.

In the Bay Area, Schubert last month used a quirk in California law to bring murder charges in her county against a teen accused in a San Francisco shooting, a move that Boudin has alleged was meant to circumvent his policy against charging juveniles as adults. Schubert defended her decision, arguing that the victim and suspect both resided in her jurisdiction, and the defendant was already facing serious charges there.

But Schubert and Pierson also said they are worried that as the pendulum of justice swings, the rights of victims are being ignored.

Patty Elliott traveled to a parole board meeting Dec. 8, the day after Gascón took office, to see whether Duncan Martinez would be released after serving more than two decades in prison for his role in her brother’s brutal 1990 stabbing death. Elliott was already infuriated that Newsom had commuted Martinez’s sentence without notifying her. But that morning, as a result of Gascón’s sweeping directives, she learned the prosecutor assigned to be her advocate was no longer allowed to argue against Martinez’s release. Martinez was granted parole, but has not been released yet.

George Gascón has promised to make sweeping changes to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office, but he will have to walk a tightrope between prosecutors who opposed his candidacy and activists promising to hold him accountable.

While the parole board granted release only in about 16% of hearings last year, a number that decreased from 21% in 2018, critics of progressive prosecutors say they fear releases will become more frequent without deputy district attorneys to oppose them. Gascón has since said that he will still send victims’ services representatives to parole hearings, but they will not be allowed to argue against granting of parole.

“I feel that the victims in any of the cases should still have representation from the county or the state,” said Elliott, adding that she understood the need to fix over-incarceration. “I don’t think the prisoner’s rights should supersede the victims’ or the family’s rights to have equal representation at the hearings.”

Not every district attorney sees the split in stark terms. Rosen said he’s “sympathetic to both sides.” Ultimately, he said prosecutors are “under no illusion” that the momentum of reform is inevitable. Rosen points out California has enjoyed historically low crime rates in recent years. Now, certain violent-crime statistics are creeping up, including homicides.

Ultimately, the degree people feel protected in their communities may determine whether prosecutors such as Gascón can stay in office and pursue change, regardless of what their colleagues think.

“When people feel safe, they feel open to reform,” said Rosen. “When people feel unsafe, when people are afraid, they don’t.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.