Latasha Harlins’ name sparked an L.A. movement. 30 years later, her first memorial is up

They gathered to gaze at the colorful new mural of a 15-year-old Black girl killed 30 years ago at a South-Central liquor store, whose name drove protesters into the streets and became a rallying cry for justice.

It was New Year’s Day 2021, and Latasha Harlins would have been celebrating her 45th birthday.

The immense painting on the front of Algin Sutton Recreation Center — in a neighborhood that many locals still call South-Central L.A. — is the first public memorial to Latasha since she was fatally shot by a Korean-born merchant who’d accused her of stealing a bottle of orange juice.

“For a long time, I couldn’t look at her picture,” said Ruth Harlins, 79, as she looked up at the vast image of her late granddaughter. She’d taken Latasha’s photos down in her home because they were too painful to look at.

“But now, I have [them] up,” she said of the photos. When she looks at them, she tells herself: “That’s my granddaughter. I miss her.”

In the decades since she was killed, the dominant visual memory of Latasha has been of her final moments, captured on a grainy security video. Two weeks before her death on March 16, 1991, a video had surfaced showing Black motorist Rodney King being brutally beaten by Los Angeles police officers, imagery that would dominate national and international news and overshadow Latasha’s death in the months that followed.

But in L.A., the girl’s story had an immediate and momentous effect on the Black and Korean communities. Latasha’s shooter, Soon Ja Du, was given probation instead of jail time, and five months later the officers involved in King’s case were acquitted. Los Angeles exploded in days of fiery destruction.

A generation ago, long before Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and the Black Lives Matter movement, the death of Latasha Harlins lit a fuse inside Los Angeles’ African American community.

Latasha’s story went on to inspire films and novels and furious dirges by Tupac and Ice Cube, and has filled countless newspaper columns. Yet many people still aren’t familiar with it, including some who walk the streets she once called home.

“The people in [this] neighborhood don’t know who Latasha was because these are new generations,” a cousin, Shinese Harlins Kilgore, told The Times over the phone. The memorial, she said, was long overdue.

“So now is our time to speak up so we won’t forget her name.”

The mural, created by visual artist Victoria Cassinova, rises over a building where Latasha spent much of her free time. She smiles warmly, offset by a flock of skyward-soaring doves, bursts of playful paint splatter and a transcription of a poem she wrote about herself a month before she died. In bold blue letters are the words “We Queens,” a phrase Latasha used often to reflect how she carried herself and felt about her loved ones.

Latasha’s family and friends hope the mural and a Netflix documentary, “A Love Song for Latasha,” which was released in September, will restore her to the community and prompt others to probe the significance of her too-brief life. A host of other events, including screenings of the film and panel discussions, is planned this year.

The documentary and mural are long-delayed steps toward honoring not only Latasha but also countless other victims of racially charged violence, UCLA historian Brenda E. Stevenson said.

“It takes a long time to memorialize anyone Black,” said Stevenson, author of “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the LA Riots.” “It took us more than 50 years to move from Negro History Week to national acknowledgment of Black History Month, and that was for the entire race.”

Born Jan. 1, 1976, in East St. Louis, Ill., Latasha was raised in South-Central L.A. By the early 1980s, her predominantly Black neighborhood was reeling from the effects of the crack epidemic, and racial tensions were bubbling between Korean shop owners and their impoverished Black patrons. When Latasha’s mother was fatally shot in an L.A. nightclub in 1985, her grandmother and aunt began raising her and her two siblings.

Despite the tragedy, Latasha earned straight A’s at Westchester High School and talked consistently about wanting to become an attorney and build programs for neighborhood youth when she grew up. She looked after her younger siblings as well as other neighborhood children, who viewed her as a big sister.

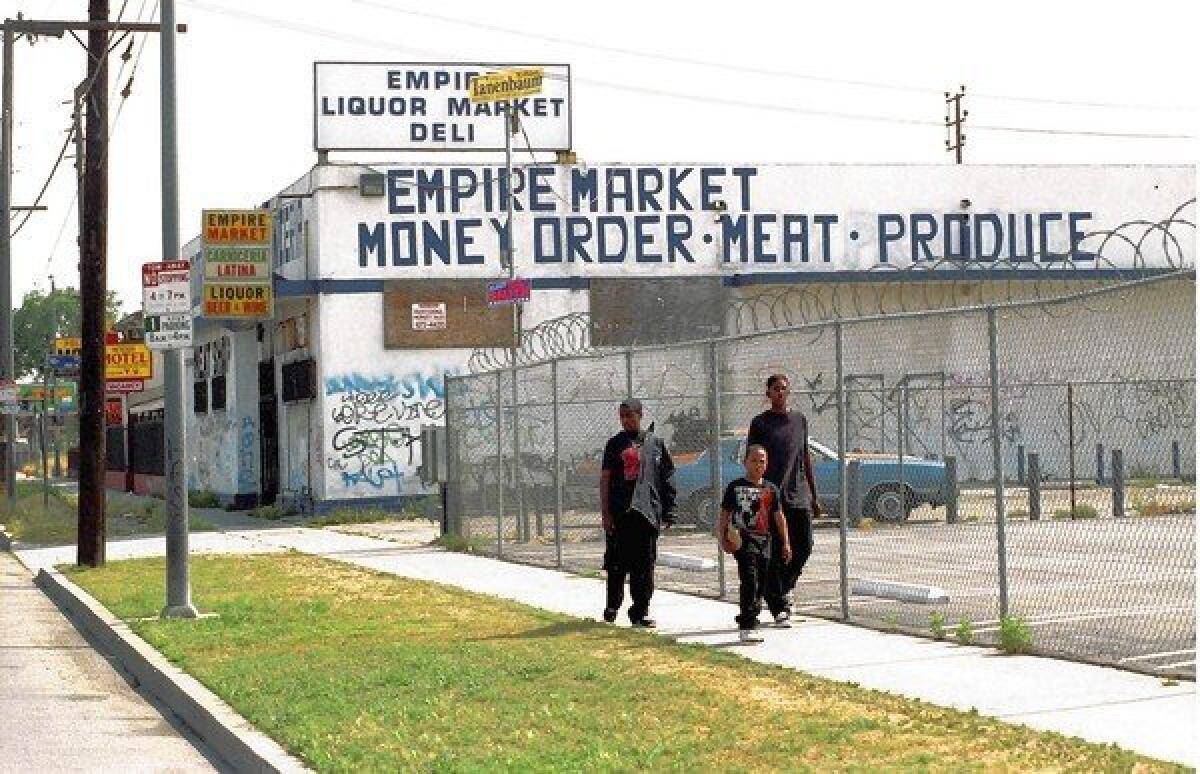

On the morning of March 16, 1991, Latasha went to Empire Liquor Market and Deli in South-Central to purchase a $1.79 bottle of orange juice for her family’s breakfast table.

When Latasha approached the store counter, Du accused her of trying to steal the bottle. Witnesses said Latasha, who put the drink in her backpack, had intended to pay and was holding $2 in her hand.

After Du grabbed her sweater, Latasha punched Du in the face and broke free, knocking the store clerk to the ground. The teenager then put the bottle on the counter, and Du picked up a .38-caliber handgun. As Latasha started to walk toward the exit, Du shot her in the back of the head, killing her instantly.

Police confirmed that there was “no attempt of shoplifting.”

A jury found Du guilty of voluntary manslaughter, which carried a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison. But Judge Joyce Karlin, who reasoned that Du acted out of fear due to previous robberies at the store, sentenced her to probation, 400 hours of community service and a $500 fine.

In court, the Black teen was depicted by the defense as a threat to the 51-year-old woman. The criminal justice system has treated other Black youths as if they were adults; they include 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was fatally shot by a 28-year-old neighborhood watch volunteer in Florida. Trayvon’s shooter, George Zimmerman, claimed to have acted in self-defense during a fight. He was acquitted.

In her documentary “A Love Song for Latasha,” director Sophia Nahli Allison strove to depict Latasha in her fullness as a teenage girl.

“I don’t want to see Latasha as an adult,” said Allison, who was a South L.A. toddler when Latasha was killed and learned of her story several years later.

“So often when Black children are murdered, we see the way they are depicted in the news. We see how sometimes the language of ‘woman’ and ‘man’ is interchanged with” that of girl and boy, Allison said. “But Latasha was a young girl. I wanted Black girls to feel reflected.”

Allison decided to tell Latasha’s story through the eyes of the people who knew her best: her cousin Harlins Kilgore, now 44, and childhood best friend Tybie O’Bard, also 44. The 19-minute documentary, filmed over the course of two years, traces their youthful memories of Latasha — going to Tam’s Burgers after school, listening to their favorite song, “Stand By Me,” on a jukebox, and playing basketball at the park.

In the film, no single actor plays the roles of Latasha or her loved ones; instead, the director used several young Black girls to show how Latasha’s fate could have happened to any Black girl at the time. And rather than employing a conventional documentary style of interviewing subjects and reenacting events, Allison adopted graphics and other visuals to mimic the memories of children, giving the experimental film a dreamlike texture.

“I think there’s such a love and there’s such a beautiful way that children remember [and] that children see stories,” Allison said. But too often we fail “to acknowledge how important that perspective is,” she added.

Unlike other films or documentaries made about Latasha or touching on her life, “A Love Song for Latasha” doesn’t depict her death or the violent conflagrations it triggered — images that O’Bard and Harlins Kilgore said they’re tired of seeing. Instead, the film simply celebrates her life.

Memorials to the civil rights era have honored its famous adult leaders, but the pivotal contributions of thousands of children and young people — the students who sat stoically at segregated lunch counters, risked their lives riding buses into the Deep South and endured savage beatings to register voters — have been less known and honored. It took more than 50 years to place a commemorative plaque in Mississippi to 14-year-old Emmett Till, who was murdered after talking to a white woman. The plaque had been repeatedly vandalized and has now been bulletproofed.

Stevenson, the UCLA scholar, said that the disregard for the traumatic experiences of children extends beyond the Black community. This can be seen in the inhumane treatment of immigrant children at the border between the United States and Mexico, the ways in which Native American children were taken from their families and placed in abusive boarding schools, and the ways in which “enslaved Black children, and those of some immigrants, were taken away from their parents to be worked to death, beaten and raped,” she added.

“Most of those persons trafficked in the world today (and historically) are women and children,” she said. “Across time and in many places, including our nation, children and adolescents have had less respect, support and protection than adults. The lack of memorialization is part of that praxis.”

Stevenson said that Black women in particular, both young and older, have been given short shrift in America’s legacy of fighting for racial justice.

Mainstream media, the general public and parts of the Black community view and respond to the treatment of Black people in the criminal justice system, and other forms of systemic racism, through a patriarchal lens, Stevenson said.

A standout example is that many people, especially outside L.A., refer to the 1992 riots as the “Rodney King” riots, she added.

“How we remember and memorialize Black life often centers mostly on the male experience, not the female,” she said.

But these gendered perceptions are shifting. When Breonna Taylor was fatally shot by officers in her Louisville, Ky., apartment last March, Black Lives Matter protesters began shouting “Say her name,” and discussions in the Black community and beyond about protecting Black women became more prevalent. These changes have led people to acknowledge the deaths of Black women like Latasha that happened generations before.

Melina Abdullah, co-founder of L.A.’s Black Lives Matter chapter and a mother of 14- and 17-year-old girls, said it’s significant to memorialize Latasha’s life even after all these years.

“Thirty years later, you’ll never get over the loss of a child,” said Abdullah, who is also a professor at Cal State L.A.

The memorial is “affirming Latasha’s life, but it’s also affirming and valuing the lives of Black girls more broadly,” she added. “That they’re not just going to be stolen and then we sit silent and say, ‘Oh well.’”

Harlins’ aunt, Denise Harlins, fought tirelessly for her niece to be remembered, and for justice to be done in her memory, by establishing the Latasha Harlins Justice Committee shortly after her death. (The California State Assembly named April 29 Latasha Harlins Day in 1998.)

Before Denise died in 2018, she told her daughter, Harlins Kilgore, and O’Bard that it was their duty to continue her work of raising awareness about Latasha and demanding change in the legal system.

“It was time for me to do something extraordinary so that I can [honor] her legacy and say, ‘What you did here in the world is not going to go in vain,’” Harlins Kilgore said of the mission she inherited from her mother. “I’m sure she’s up there in heaven smiling, like, ‘You did a good deed.’”

In addition to the committee, Harlins Kilgore and O’Bard are starting another nonprofit organization that will provide resources and scholarships for L.A. youth — a dream that Latasha often talked about.

More events are scheduled in coming months to explore and commemorate Latasha’s life.

On Thursday and Friday, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will host screenings of “A Love Song for Latasha,” followed by conversations with Allison, the filmmaker.

A group of Black girl artists from an organization called A Long Walk Home, which seeks to empower youth to fight violence against women and girls, is responding to the documentary by creating its own artwork to celebrate Latasha, a Netflix representative said.

And from Feb. 11-23, the documentary will be included in the New York Museum of Modern Art’s “The Future of Film Is Female, Part 3” series, which highlights contemporary films directed by women. Additional activations are expected throughout the year.

At the South L.A. memorial site on Latasha’s birthday, family members said they now have hope that the memory they cherish will live on.

“This community can now begin to heal,” O’Bard said with wet eyes as she gazed up at the mural. “It shouldn’t have taken 30 years, but we’re here, and she’s here to stay.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.