What are these atmospheric rivers that bring heavy rain and snow to California?

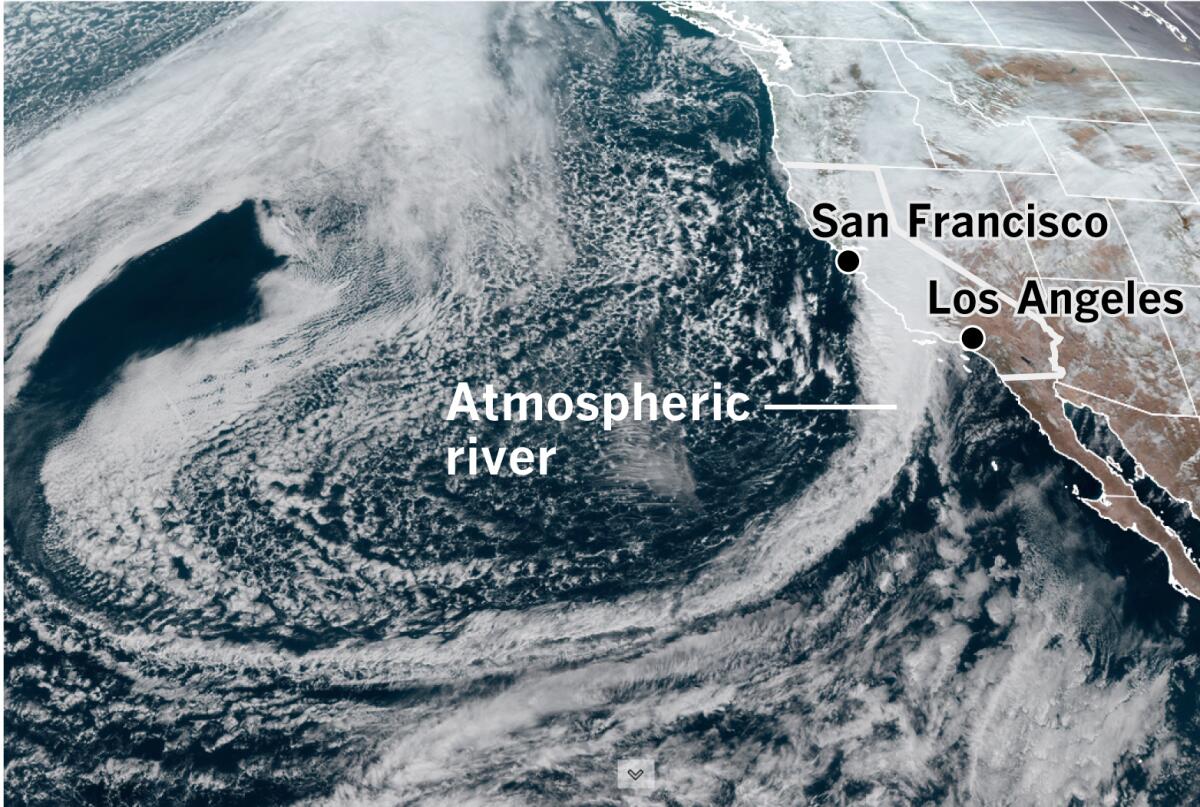

An atmospheric river — a plume of moisture that has been likened to a river in the sky — has brought heavy precipitation to the Central Coast. Now it will sag southward and bring rain and mountain snow to Southern California on Thursday night into Friday morning, the National Weather Service said.

How much rain can such a system produce? Some locations in San Luis Obispo County have received 13 or 14 inches — what the weather service has called “epic amounts of rainfall.”

A winter storm swept over much of Southern California, dusting mountaintops with snow and bringing traffic to a standstill on several passes.

The front and the moisture plume associated with it will be weaker and will be accompanied by strong south to southeast winds when they arrive in the Los Angeles region.

What are atmospheric rivers?

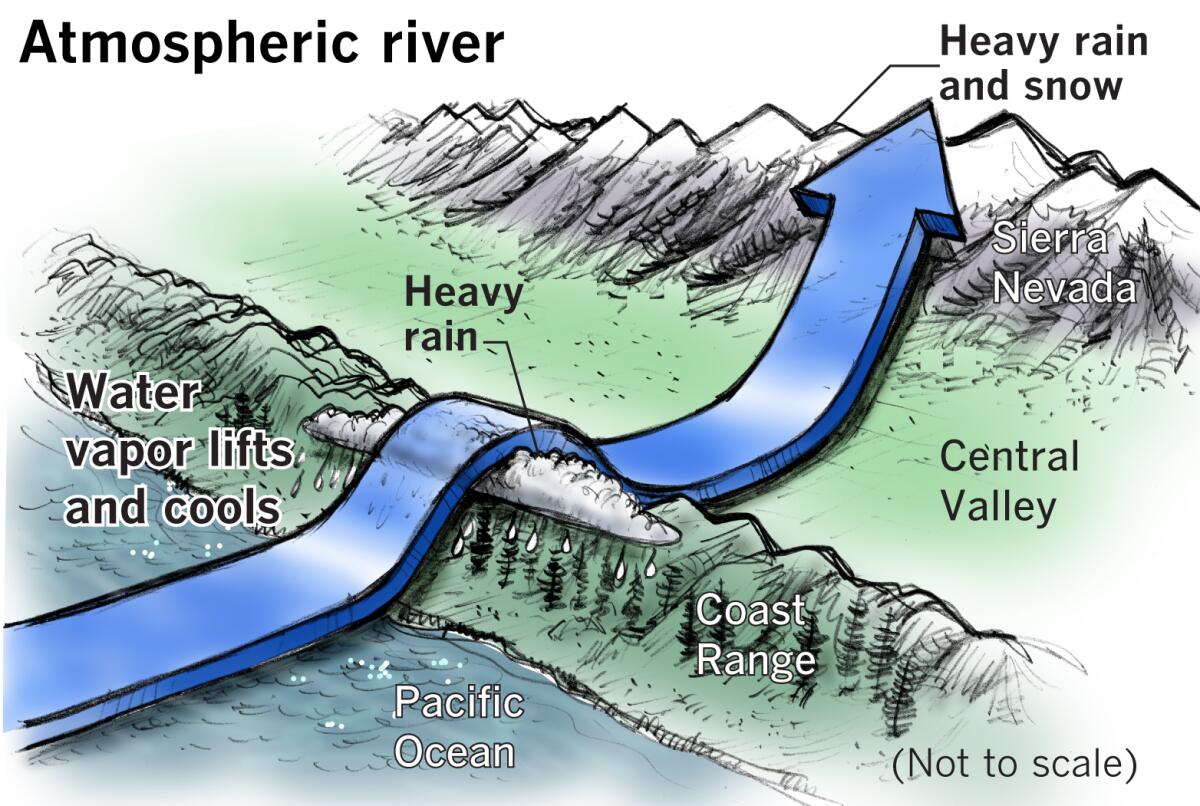

Atmospheric rivers are concentrated streams of water vapor in the middle and lower levels of the atmosphere. They’re like a continuous channel of moisture streaming across the ocean without interruption until they encounter an obstacle such as the coast ranges in California. These obstacles force the stream to start shedding its burden of moisture.

Some atmospheric rivers are weak and produce beneficial rain, and some are larger and more powerful, causing extreme rainfall, floods and mudslides.

On average, 30% to 50% of the West Coast’s annual precipitation comes from a few atmospheric rivers each year.

“In L.A. it doesn’t rain or drizzle every day during the winter like it does in Seattle,” said climatologist Bill Patzert. “Heavy rain comes in five, six or seven events. There are usually less than 20 days of rain, and less than 10 days of significant rain each season.”

Atmospheric rivers are roughly 500 miles wide and can transport water at a rate per second equivalent to 25 Mississippi Rivers or 2.5 Amazon Rivers, according to Marty Ralph, an expert on atmospheric rivers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

When this atmospheric stream, bloated with moisture as it is, meets California’s mountainous coastal topography, it is forced up and over the higher terrain. This is called orographic lift. The moist air plume cools as it gains altitude, and the moisture condenses, falling as rain.

Mountain slopes facing the ocean and directly into the oncoming atmospheric river of moisture tend to receive the heaviest rain, while some areas such as San Jose and parts of the Salinas Valley, for example, will be in the rain shadow of these mountains and will receive less as a result.

An atmospheric river hitting the Central Coast will continue across the Central Valley and climb the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. These peaks are so high and give the atmospheric river such a workout that almost all the rest of the moisture is wrung out of it, leaving the mountains smothered in a blanket of snow because of the cold at that high altitude. The Great Basin beyond the Sierra is largely left in a gigantic rain shadow.

A look at the map shows that California’s deserts are a product of mountain ranges, including the Transverse Ranges in the south, that starve inland areas of a moist flow off the ocean.

The mountain snowpacks serve as the state’s water bank under good conditions, and the snow gradually melts through the warm months, replenishing streams and reservoirs.

Storms such as these are driven by an upper-level low-pressure system dropping south and often setting up off the Pacific Northwest. These low systems have counterclockwise circulation that will pull a plume of extremely moist air toward the California Coast, creating an atmospheric river.

Sometimes the moisture is tropical, originating near the Hawaiian Islands. As a result of its origin, such systems will be warmer, causing snow levels to be higher.

An atmospheric river such as this is popularly known as a “Pineapple Express.” “All Pineapple Expresses are atmospheric rivers, but not all atmospheric rivers are Pineapple Expresses,” said Drew Peterson, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Monterey.

Why is there concern for the recent burn scars?

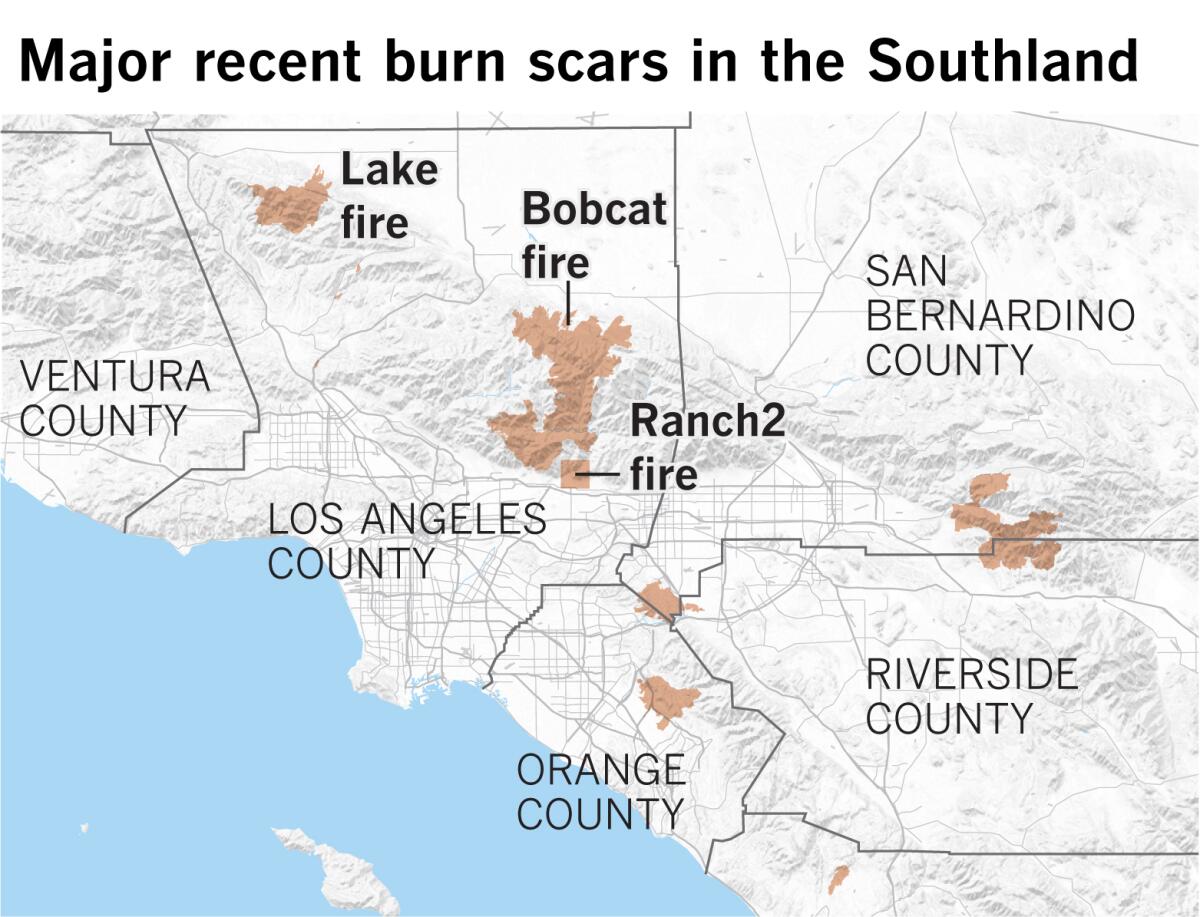

In the case of the current atmospheric river event, forecasters have expressed particular concern about heavy rain causing debris flows in burn scars left by the Bobcat, Lake and Ranch2 fires.

Although rainfall amounts are expected to be lower than those on the Central Coast this week, they could still be substantial in the L.A. region, and short-duration intensity could be a problem at higher elevations, especially with downpours from thunderstorms.

“Thunderstorm potential is fairly low and will likely be delayed until tonight and Friday when the colder unstable air moves over the area,” Eric Boldt, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard, said Thursday.

But massive amounts of rain aren’t needed to create a dangerous situation. For example, the Montecito mudslide in Santa Barbara County on Jan. 9, 2018, following the Thomas fire, occurred after only about a half-inch of rain. But that rain fell in about 5 minutes, and produced debris flows 15 feet high.

The moisture plume coming from the south this time will be perpendicular to the region’s Transverse Ranges, mountains such as the San Gabriels, that run west to east.

These are geologically relatively new mountain ranges that are high and rise abruptly, forcing the moisture plume in the lower and middle levels of the atmosphere to rise quickly, enhancing the rainfall. This lifting effect means that mountains wring out the maximum moisture on the areas blackened and denuded by recent fires — the worst possible place for heavy rain to fall.

Hundreds of canyons and arroyos line the San Gabriel Range from the San Fernando Valley to the Inland Empire. Intense rains are rapidly funneled by these features, carrying mud and debris into vulnerable foothill communities below the burn scars.

Brief downpours can be dangerous, and residents living near the burn scars should always be alert for quickly changing conditions and follow evacuation orders.

“As the storm approaches, those living below the burn areas in the San Gabriel Mountains have mudslides on their minds because of the Los Angeles region’s long history of punishing floods and debris flows,” said Patzert. “The mudslides can’t be predicted, but they can be anticipated. Since the most intense rainfall will occur overnight, Angelenos in threatened locales need to keep vigilant.

“After almost 10 months of record-breaking drought, heat and fires, mudslides after heavy rains are almost inevitable,” said Patzert.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.