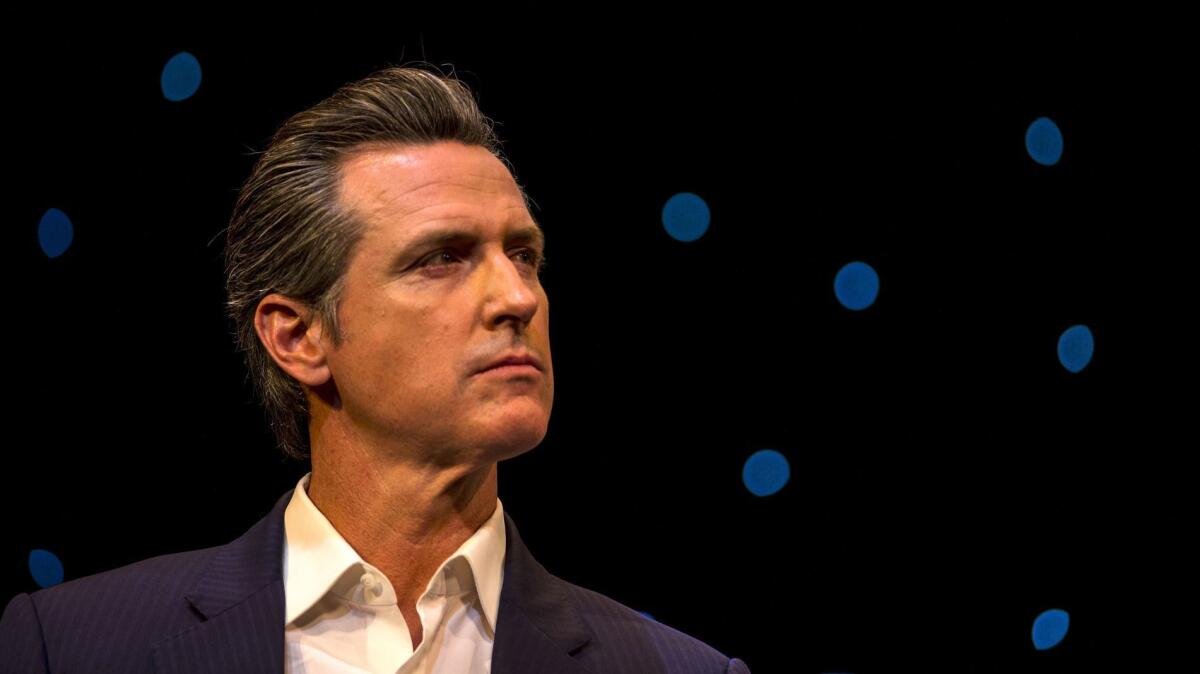

The pandemic fuels long-shot recall effort against Gov. Gavin Newsom

SACRAMENTO — Among the many catchphrases coined by Gov. Gavin Newsom during his livestreamed briefings about California’s COVID-19 emergency is his promise to point out “trend lines before they become headlines” — a reminder that warning signs often appear long before things reach a crisis point.

It’s an observation that could also apply to Newsom’s political fortunes. As he slogs through an unparalleled crisis, the 53-year-old Democrat finds himself staring at the most unexpected of trend lines: the very real chance of a special statewide election in 2021 in which voters could remove him from office.

Only once has a California governor faced a recall: the 2003 election that cut short the tenure of Gov. Gray Davis. By most measures, the current circumstances make for an ill-fitting comparison — whereas Davis had narrowly won reelection the year before and was widely unpopular, Newsom won the governorship in 2018 by the largest margin in modern history and has maintained a strong job approval rating.

But public reaction to recent events has caught Democrats by surprise. As Californians reel from a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases and a gloomy economy, some have taken aim at Newsom over his administration’s restrictions that have closed businesses, implemented overnight curfews and limited family and faith traditions.

The timing has proved lucky for the angry activists who launched a recall petition against the governor in the early spring, an effort recently joined by a cadre of professional Republican political consultants and fundraisers and boosted last month by a largely unnoticed court ruling. Not unlike the effort in 2003, the campaign has tapped into a vein of discontent, a combination of fear and malaise that led to Davis becoming the first and only governor recalled in California history.

Newsom hasn’t publicly commented on the recall effort, deflecting a reporter’s question Monday by commenting on the state’s work in distributing the COVID-19 vaccine. Nor have most Democrats, seemingly worried about boosting what they see as an unjustified effort.

Others say the situation could become more worrisome if the governor doesn’t fight back.

“Don’t just ignore it or engage in wishful thinking that it won’t qualify for the ballot,” said Garry South, who served as Davis’ chief political strategist and consulted for Newsom when he briefly ran for governor a decade ago.

Davis tried to ignore the unprecedented campaign launched against him until the special election was called — by which time it had gained enough momentum to attract the candidacy of the celebrity who rode it to victory, Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican.

South argues that Newsom should fight back much earlier.

“He needs to really start constructing a war council that can help him navigate the process,” he said. “With social media, this thing’s already caught fire on the right.”

Voters who seek to remove an elected official don’t have to prove malfeasance, under rules dating back to the inception of California’s recall process more than a century ago. Any reason will suffice, and, as the California Constitution explicitly states, the justification “is not reviewable” by any state officer.

The loose requirements of the process probably explain why so many recall petitions have been filed over the years — but also why most of them have failed to catch on. Of 165 attempts against a statewide officer or member of the Legislature, only 10 have qualified for the ballot. Six of those elections — all of them, other than the Davis recall, involving legislators — were successful. The most recent resulted in the removal in 2018 of an Orange County state senator, who won his seat back last month.

Half a dozen recalls have been filed against Newsom since 2018, the first only two months after his inauguration. The recall petition now under consideration lists an assortment of grievances: broad swipes at his stance on issues such as illegal immigration, taxes and homelessness, and specific criticism of his moratorium on the death penalty.

But the pandemic upped the ante for Newsom’s foes.

State public health rules dictating which businesses can remain open and which activities are allowed have been assailed as arbitrary. Legislators have bristled at the governor’s use of executive power and the many foibles of California’s unemployment agency, led by his appointees. A rising chorus of parents and educators have demanded a statewide policy covering when to reopen school campuses; so far, those decisions have been left largely to local school districts, a matter particularly galling to those who note that Newsom’s four children returned this fall for limited in-person teaching at a private school in Sacramento.

The most flammable moment came last month, when Newsom attended a dinner at a pricey Napa Valley restaurant. Photos leaked to a Los Angeles TV station showed the governor and his wife sitting in tight quarters with others, none of whom were wearing masks.

Some conservative critics saw his apology as insincere.

“That smugness was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Ray Appleton, who hosts a talk show on KMJ-AM in Fresno, told listeners last week. “It’s like someone just threw the switch and said, ‘There it is, we’re going to get this guy.’”

Doing so will require more than just motivation. A recall election hinges on collecting voter signatures equal to 12% of the total ballots cast in the most recent gubernatorial election — in this case, the endorsement of some 1.5 million voters. Because even the best petition drives end up with a portion of signatures deemed invalid, the assumption is that the Newsom recall effort needs the endorsement of at least 1.6 million voters, perhaps closer to 2 million.

Under the normal election calendar, which allows 160 days to gather signatures, the effort would already be over. But in the same way the public health crisis has upended the norms of everyday life, it has prompted an exception to the rules of a recall.

Last month, a Sacramento judge gave recall proponents an additional 120 days — through the middle of March — to gather signatures, pointing to recent rulings that provided extra time for backers of two proposed ballot measures who cited the challenges of circulating voter petitions under California’s coronavirus restrictions.

“I think it was a mistake for Democrats not to appeal that decision,” South said.

Dave Gilliard, a veteran Republican strategist and one of the architects of the successful Davis recall petition drive, recently joined the nascent effort. His group dusted off the name and logo of the 2003 campaign — “Rescue California” — and is raising money for signature gathering.

“I think the timing is right,” Gilliard said. “This frustration with the pandemic — he’s the guy in charge.”

Even so, the political odds favor Newsom.

Gilliard acknowledges that there’s a narrow window in which to raise enough cash. His group recently touted endorsements from former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee. But for every Republican who excites would-be donors, the Newsom political team will see opportunities to paint the recall as a partisan effort to do what GOP candidates haven’t been able to do in California since 2006: win a statewide election.

Dan Newman, a political advisor to Newsom, said the governor is focused on “getting us through the home stretch of this COVID crisis” and criticized the recall as “a dangerous and toxic brew of ambitious Republican politicians and pro-Trump, anti-mask, anti-vaccine extremists.”

In the parlance of Newsom, the “trend line” of the recall movement is not firmly set. Though organizers of the campaign say they have collected close to 800,000 signatures, slightly more than half that number have been turned in to elections officials.

And if it does make it to the ballot, some suggest looking not at California’s 2003 recall election for a preview but instead at the one that sought to remove Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker in 2012. Walker not only beat back the recall but won reelection two years later. Newsom, already a national political figure with $15 million in campaign cash in the bank, could easily come out of the experience stronger than ever.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.