Column One: Three daughters mourn fathers in a sisterhood of grief

Her voice flittered from the screen, filling her father’s New York City hospital room.

From a couch in her home office in Los Angeles’ Mar Vista neighborhood, Carolyn Freyer-Jones watched through her laptop as a ventilator forced air into his lungs. She knew he didn’t want to linger — he had made that clear during end-of-life conversations. I love you, she told him, over and over. Thank you, and I love you.

“Don’t hang around for us, Dad,” she assured him. “If you want to go on your birthday, you can go.”

Later that afternoon — nine days after testing positive — her father, Hugh Freyer, a retired banker from the Bronx who for years committed himself fiercely to his sobriety, died on his 86th birthday.

Eight days later, Serena Dobbie, a 37-year-old real estate agent, stood near her own father’s hospital bed in Upland, Calif., crying behind two masks and searching for words to say goodbye. A month later, Dolly Spadaro, a 38-year-old resource analyst at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, rushed to LAX and sobbed through both legs of her flight to Lebanon, where she’d sit down with her mother and break the news of her father’s passing.

The three daughters — strangers who crossed paths in a private Facebook group for people who’ve lost loved ones to COVID-19 — are now part of a sisterhood of communal grief.

Started in April by two women whose fathers died of the virus, the group — whose ground rules include “no politics” and “science-based posting only” — now has 3,700 members across the globe who share photos, send one another encouraging notes and commiserate over how much they’re dreading their first holidays without their loved ones.

At least once a day, Freyer-Jones scrolls the page and leaves a variation of the same message on a new post: “I’m so sorry that you’re here. You’re not alone.”

As thousands of people have privately grieved deaths, illnesses and the stresses of living through a sudden recession while in isolation, many have turned to social media for support, solace and answers. Facebook alone hosts dozens of groups for COVID-19 “long-haulers,” who swap information about their lasting symptoms.

More formal avenues of support have also cropped up during the pandemic. Therapists across the country host COVID-19-related support groups by phone and video conference. In Los Angeles, Kaiser Permanente started bereavement groups, conducted weekly by phone in English, Spanish and Armenian.

The scope of collective grief and isolation is unparalleled in recent history, said Deborah Serani, a psychologist and adjunct professor at Adelphi University in New York. And the next several weeks could be especially hard for many families, she said, adding that it’s important to find ways to incorporate memories of loved ones into holiday rituals and traditions.

“It’s a way to say, ‘What would my Dad wish we could do?’” she said.

For Freyer-Jones, who works as a life and business coach, one of those new rituals is the Friday Minute, a movement she started urging people to set aside 60 seconds a week to think about someone affected by the coronavirus — perhaps a sick friend, a family in mourning or someone who has lost income or educational opportunities.

She views it as a time to slow down — a grounding moment amid the magnitude of our suffering.

On a recent morning, while broadcasting live from her Instagram account, @thefridayminute, Freyer-Jones — donning a black baseball cap, one of more than 200 from her father’s collection — led her followers through 60 seconds of meditation. She said she thinks often of other grieving families whose stories she has learned — the other devastated daughters who had far fewer years with their own fathers.

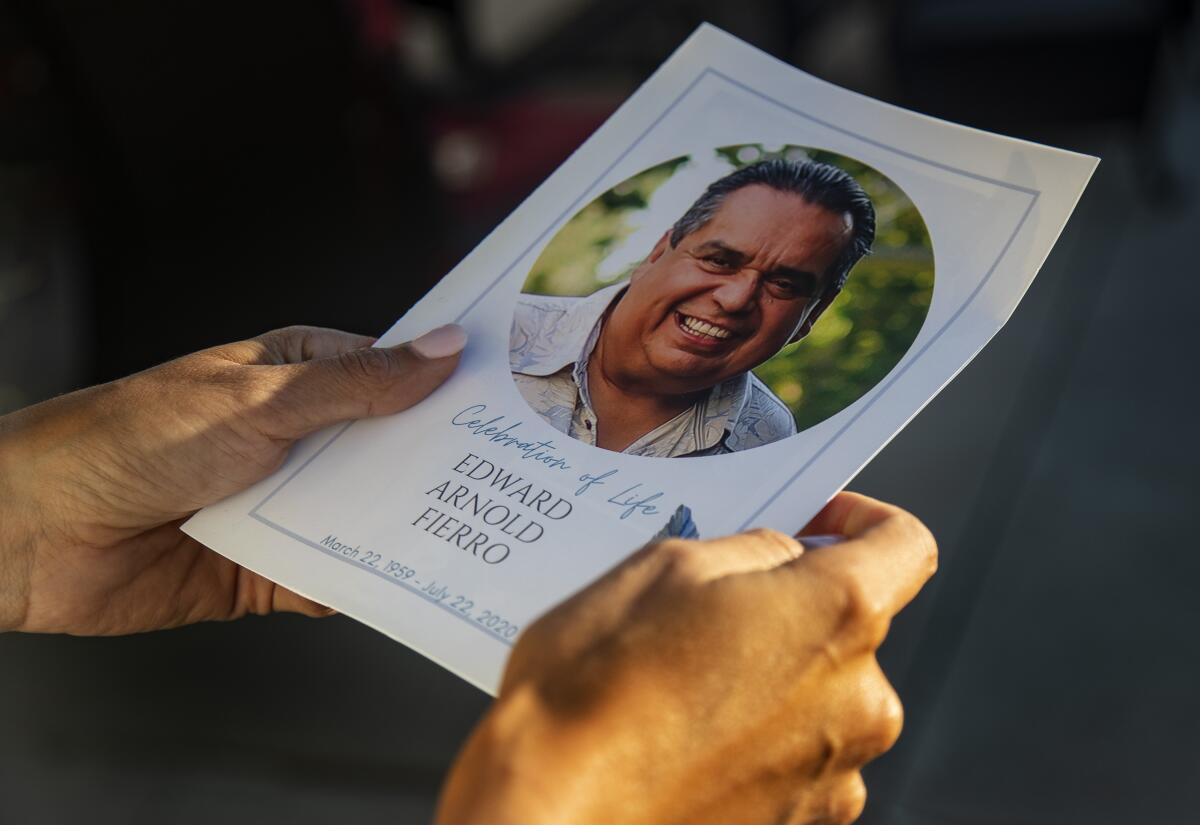

Women like Dobbie, who watched on a Thursday in July as her 61-year-old father, Eddie Fierro, walked slowly from her childhood home in Rancho Cucamonga, struggling to breathe.

It wasn’t safe to share a car, she knew, so he drove himself; she followed behind, watching as a hospital employee pushed him into the emergency room in a wheelchair.

“I never, ever, ever, ever would have thought he wasn’t coming out,” she said.

At first, he had enough energy to text Dobbie and her younger sister, Lauren Andrews, photos of himself wearing a mask in his hospital room, but soon doctors were mentioning remdesivir and convalescent plasma. He responded well to the plasma treatment, Dobbie said, and she was able to talk to him on the phone. I feel like I could walk out of the hospital today, he told her.

A day later, he went into cardiac arrest; five days later, he died.

In an instant, Dobbie and her sister, both in their mid-30s, had lost their father and become caregivers for their mother, who has late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The sisters wrapped up pending jobs from their father’s custom cabinet company — S&L Design, for their initials — and immediately began clearing out their childhood home, knowing they’d soon need to put it on the market to cover the cost of caring for their mother in a skilled nursing facility.

Sometimes relatives dropped off food outside the door, but other than their husbands, no one could come in to help. They knew how contagious this virus is — it had also sickened and hospitalized their mother, their uncle, their grandfather and their grandmother.

Dobbie’s days blurred with tears and calls from the Internal Revenue Service. On Halloween, she saw people on social media posing in spiky red orb costumes. Some of her close friends refused to wear masks — calling the coronavirus a hoax.

It felt as if the only people who truly understood her — who knew how triggering it could be to hear a sneeze followed by a joke about “the ’rona” — were the other members of the Facebook group, which she had stumbled upon months earlier while searching for events memorializing the dead. She hasn’t yet shared her own story with the group, Dobbie said, but she comments on as many posts as she can.

Dobbie’s father, a lifelong Dodgers fan, died July 22, hours before the delayed season opener. During the bottom of the eighth inning, when a single aluminum balloon floated onto the field, she wondered if it was him sending a sign. A few weeks later, while driving to an anniversary dinner with her husband, another aluminum balloon floated overhead. This time, she knew.

She has found some peace, Dobbie said, in knowing that her father never lived a day without his beloved wife and that, because of the severity of her condition, she will never fully know a day without him. From scrolling the Facebook group, Dobbie knew that many daughters were simultaneously grieving their fathers and comforting their mothers.

One of those was Spadaro, the NASA employee, who emigrated 12 years ago from Beirut to Los Angeles. She was at work one afternoon in August when she peeked down at her phone and saw that her brother was calling. Her heart sank.

Several days earlier, her 65-year-old father, living in Beirut, had lost his sense of smell and started to sweat though the night. Farid Dahdal tried to nurse his symptoms at home, thinking it best to avoid hospitals, many of which had been damaged by the massive explosion in the Mediterranean port city earlier that month.

When he finally went to the hospital, his blood oxygen level had dropped to 93%, but he was told he could still manage at home. He returned to the hospital the next day and was admitted, even as doctors assured him that his vitals and prognosis looked good. But his breathing became increasingly labored; he was put on a ventilator and the next day went into cardiac arrest. Doctors tried for 40 minutes to revive him.

Spadaro’s cousin, a doctor in Lebanon, broke the news to her brother, who then called her. Their mother, who was quarantining alone after testing positive herself, was unaware, and the siblings couldn’t bear to tell her by phone. What if she fainted? And local relatives couldn’t visit her at home, risking infecting themselves.

Spadaro and her two brothers frantically booked plane tickets and took coronavirus tests, knowing they’d need negative results to be let into Lebanon. If our mother calls, they begged the hospital, please say our father isn’t doing well but remains in critical condition.

When they arrived at their family home in gloves and robes and masks, they sat down and gave their mother the news. She sobbed, but Spadaro couldn’t risk giving her a hug.

Spadaro will return to Beirut at Christmastime, but she worries that the home will feel achingly empty. Dad won’t be there cuddling his cat or playing the piano or accordion. Even the thought of putting up a tree makes her feel nervous.

Her parents had paid off their home earlier this year, and her father’s dream of retiring in the U.S. had seemed like more than a distant hope. Maybe, Spadaro remembers thinking, we’ll all finally be in the same place.

“COVID robbed me of my dreams,” she said. “I can’t dream right now.”

She finds deep comfort and validation in the Facebook group. Sure, many people survive the virus, but the group reminds her that there are many others whose recently healthy loved ones did not. It was deeply therapeutic to receive so much encouragement after sharing her story, she said, and these days, she has a little more energy to encourage others, as well.

The only other thing buoying her spirit now, she said, is her faith — her confidence that this is temporary, and heaven awaits. Sometimes sadness hits like a wave, and she repeats a verse from Corinthians 2 like a mantra: We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.