Who realized how wide open our lives were until the pandemic shrank them down last spring?

Who really thought about what a privilege it was to be able to explore our city freely — to peer into its windows and shop in its stores and eat out at its crowded restaurants and frequent its crowded bars?

Who stopped in the course of a busy day out in the world to acknowledge how important such daily habits were in keeping the Los Angeles we love alive and vibrant?

Now every week there is news of more longtime businesses closing, given the final shove by pandemic neglect after holding on for so many years.

This week it was Jerry’s Deli in Studio City, which announced on Instagram that it was shutting its doors “for the foreseeable future” after 42 years on Ventura Boulevard.

“To say that 2020 has been a year of uncertainty would be an understatement,” read the post. “The world as we knew it has changed and is still changing.”

One day, our world is so big. The next it shrinks. It gets smaller than small.

I’m hoping our narrower lenses can have at least this upside: that they can help us focus in collectively on those one-of-a-kind L.A. places that we’re willing to fight hard for and resolve not to lose.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot since I discovered the work of Kieran Wright, who moved to L.A. from New Zealand three years ago, and used to love to seek out his new home’s most distinctive historic businesses and roadside attractions. He researched the oldest restaurants and visited them one by one. He sat in the very oldest, the Saugus Cafe in Santa Clarita, which opened in 1905, and imagined those who’d been there before him, the stars who’d visited while filming nearby in Hollywood’s Golden Age.

This year, after he was first furloughed and then laid off from his suddenly nonsensical Qantas Airways job marketing the delights of Australia to Americans, his life shrank smaller than most. The pandemic turned him into a miniaturist paying tribute to our treasures.

For the past seven months, from a nook in the corner of his mid-city bedroom, Wright has been meticulously creating heartbreakingly perfect tiny versions of some of the L.A. area’s most beloved old-time spots: the Tiki-Ti bar on Sunset Boulevard, Rae’s Restaurant in Santa Monica, Taix in Echo Park, Fugetsu-Do in Little Tokyo.

When from the confines of my little home office I recently stumbled upon his rendering of that Little Tokyo confectionery, which opened in 1903, its evocative power took me by surprise. My eyes welled up. I thought, how long has it been now since I’ve been there?

All over Los Angeles are these places we’ve long loved — which aren’t seeing that love so much right now. I am worried about their survival and about their employees. I am worried about how many of them will be there to welcome us back when we come out of our cocoons.

In the normal course of life, of course, many of us love such places erratically. Sometimes we forget about them. We discover new spots or we move too far away. We mean to visit more often than we do.

When The Times was downtown, I would wander into Fugetsu-Do about once a week and buy something small and beautiful, perhaps a little mochi in the shape of a mushroom or a plum. But then the newspaper moved to El Segundo and I stopped by less often.

And then this spring, those of us who were able to do so stayed inside our homes to stay safe and mostly gave up such visits altogether.

This isn’t the normal course of life — and so many of the beloved places we aren’t patronizing enough are hurting. So many already have disappeared with barely a word.

Before the pandemic, we would often get a little advance notice.

“Now it’s often like a very abrupt death,” said Adrian Fine, director of advocacy for the Los Angeles Conservancy, a nonprofit membership organization that tries to draw attention to and help protect and revitalize L.A. County’s historic architectural and cultural resources.

Last fall, the conservancy began highlighting L.A.’s legacy businesses, which it defines as places that have been around for a quarter-century or more and are mainstays of their communities. On its site and on social media, it has been telling stories of such places, which are often family owned, and asking people to share more of them. The hope is to proactively draw attention to a diversity of longtime businesses from neighborhoods all over the city, to help get them support and attention before they’re in crisis and on their last legs. The pandemic obviously has given the campaign a different kind of urgency.

That is one reason why the conservancy plans to do everything it can to bolster a fledgling effort to create a city-sponsored legacy business program.

As Kimberly Holman-Maiden’s family pub struggled, she set out to help other Los Angeles mom-and-pops survive.

In the summer of 2019, City Councilman Curren Price proposed that the city’s Economic and Workforce Development Department study programs other cities have created to help legacy businesses, and report back with recommendations. The City Council passed his motion that September. But the pandemic slowed things down. Now the EWDD, with help from the city’s Office of Historic Resources, is readying to present the report.

San Francisco offers one great model, said city planner Ken Bernstein, who manages the Office of Historic Resources. That city, in an effort to preserve its uniqueness in the face of rampant development, first created a registry of legacy businesses in order to promote them and then set up programs to offer financial and technical assistance to the businesses themselves and grants to landlords that agreed to extend their leases for 10 years.

In L.A.’s current financial crisis, new spending isn’t possible, Bernstein said — but the city’s recognition and promotion of legacy businesses could help them a lot. And there might be ways to create private and philanthropic partnerships to offer financial support.

“We see this as building upon our work in helping to preserve the places that help define Los Angeles’ identity. It’s not only about preserving significant architecture,” Bernstein told me. “When you have a business that operates for decades and then suddenly closes, it’s one of the factors that immediately generates a sense of loss or cultural displacement within that neighborhood and that begins to undermine a community’s sense of well-being and cohesion.”

Wright, the miniaturist, understands this — which is why he gave away his Fugetsu-Do miniature, choosing a winner from among those who showed him that they’d donated at least $20 to the Little Tokyo Small Business Relief Fund. His giveaway raised about $5,000.

“These places are so much more than just brick and mortar,” he told me.

Wright fell in love with L.A. right after moving here, by the way, in that special transplant way I know well, when you can’t believe how much more there is than the cliches you’ve been fed, how much history and texture there is in a place often typecast by outsiders as hollow and history-less.

Diamond Bakery on L.A.’s Fairfax Ave. has survived a lot over 74 years. Loyal customers and a GoFundMe campaign hope to carry it through the pandemic.

In New Zealand, there were ersatz, American-style ’50s diners, with shiny black-and-white checkerboard floors.

In L.A., Wright found himself in real ones, well worn and scuffed. He loved them especially for that wear.

And it is that evidence of lived history — rust on the Rae’s sign, a dumpster and trash bag alongside a grime-smudged brick wall at Tiki-Ti — that helps make his miniatures seem so extraordinarily alive.

He got the idea to make the first miniature, he said, early in the spring, when he and his boyfriend saw Walt Disney’s miniature collection on a visit to the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco. Then he was having breakfast at Rae’s, admiring its Googie style, and wondered if he could figure out how to make a miniature version. He spent a lot of time watching YouTube how-to videos and got help from other California miniaturists.

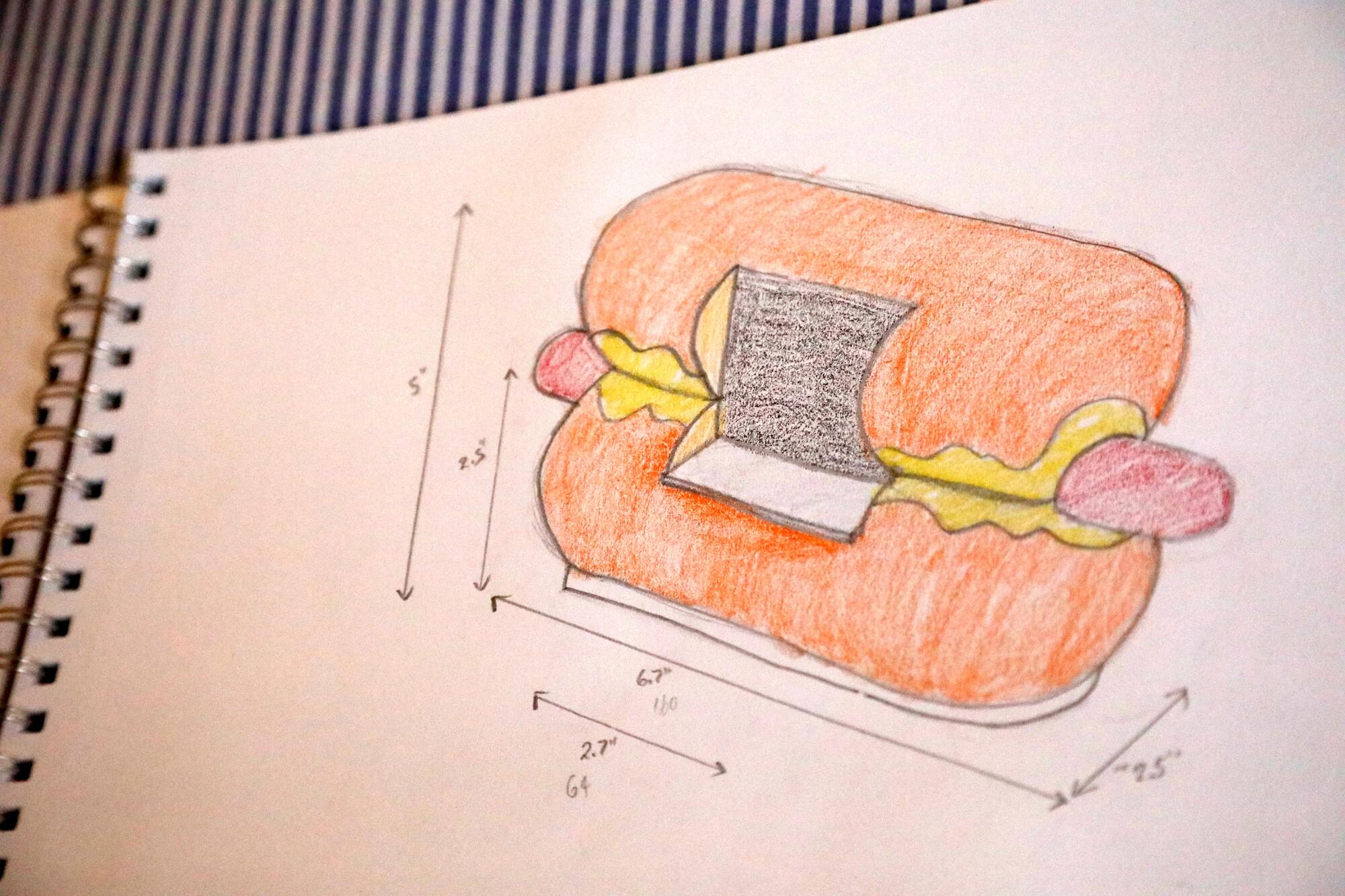

When he started posting his work on Instagram as @smallscalela, people immediately started asking to buy it. Annie Given, an L.A. native, reached out right away when she saw his miniature Tail o’ the Pup, which has been in storage far longer than he’s been in L.A. and which he reproduced from photographs. She used to go to the hot-dog-shaped hot-dog stand every Sunday after Hebrew school, she told me. It’s dear to her heart. And now her miniature of it has proud placement in her Hancock Park living room.

Joshua Tuberville, who has loved places with history since earliest childhood growing up in Camden, Ark., whose downtown “was kind of frozen in the ’50s or ’60s,” told me he started messaging Wright right away after Tiki-Ti posted his really small version of the already very small bar. He suggested Wright make a version of the wonderful facade of Morgan Camera Shop, which has long sat empty on Sunset Boulevard. Then he commissioned one for himself. Like Given’s miniature, it has prominent placement in his living room in Jefferson Park.

“You want the great places to survive,” he told me. “And I hate to see places that are not blight getting demoed to build something unremarkable.”

L.A. landmarks that did not survive, by the way, are the specialty of another miniaturist, C.C. de Vere, born and raised in L.A., whose homages to the disappeared can be found on Instagram under the poignant name @littlelostangeles.

“There’s so much that’s gone but so much that’s left that’s worth saving,” she told me.

Maybe as a city we can come together to help.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.