Latino immigrants who’ve survived electoral violence are anxious about Nov. 3

“I never thought this could happen here.”

An uneasy sensation eats away at Aldo Waykan, a Guatemalan businessman and translator who does not quite understand what is happening in his adopted United States.

He came here in 1990 seeking refuge from a brutal civil war that tore apart his native country. But the tense scenario unfolding before the Nov. 3 election reminds him of what he left behind in his Central American homeland, where he was abducted and beaten by paramilitaries in league with the national government.

For some Latinos with firsthand experience of political violence, revolutionary upheaval, voter suppression and stolen elections, the countdown to election day is stirring old anxieties. Compounding the stress for some is the fear of becoming targets because of President Trump’s anti-immigrant harangues and the white supremacist groups they appeal to.

“Going to the extreme of weapons is uncomfortable,” Waykan said. “You feel a fear, because it is a threat to the community, to the democracy of the country and, of course, it does remind me of what happened in Guatemala, because by wanting to use weapons he wants to forcefully impose his ideas.”

Some political analysts have likened the charged atmosphere of this election season to the 1960s, when the social movements that culminated in passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts provoked a backlash of suppression and intimidation against Black Americans.

The mobilization of extremist groups like the Proud Boys and the spectacle of last summer’s political street clashes remind some Latinos of the crackdowns that were their daily bread during years under military rule. Some survivors of fratricidal conflicts in Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua — which were financially fueled by the United States government — are experiencing flashbacks, induced by post-traumatic stress disorder, of torture, disappearances and murders.

“It’s like living those moments from where all these social convulsions began in the ’80s and ’90s, I think that for most of the people who migrated for that reason — and who are the majority — they find it worrying,” said Ester Hernández, an anthropologist at Cal State Los Angeles.

Regardless of who wins the presidential election, some analysts fear that high levels of partisan polarization and distrust have made violent outbreaks all but inevitable. According to the “hate map” published by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the number of hate groups rose from 918 in 2016 to 941 in 2019.

“The Trump presidency has ignited them. It is very difficult to reverse that process now,” said Raúl Moreno Campos, professor of political science at Cal State Channel Islands.

“Everything indicates that there is going to be violence and a social outbreak,” he added.

Salvador Sanabria, a Salvadoran former student activist, knows what can happen when elections are sabotaged or the losing party refuses to accept the results.

In the 1972 presidential contest in El Salvador, pitting José Napoleón Duarte against Col. Arturo Armando Molina, a sudden power outage caused election polls to shut down. The capital, San Salvador, went dark and shouting rang out at voting centers.

“That was the moment the regime used for its political assault troops to enter the electoral precincts and fill the ballot boxes with ballots in favor of their candidate,” said Sanabria, who was 12 at the time.

The colonel’s victory was denounced internationally as fraud, helping to set the stage for the 12-year civil war that broke out in 1980 and ultimately took 75,000 lives.

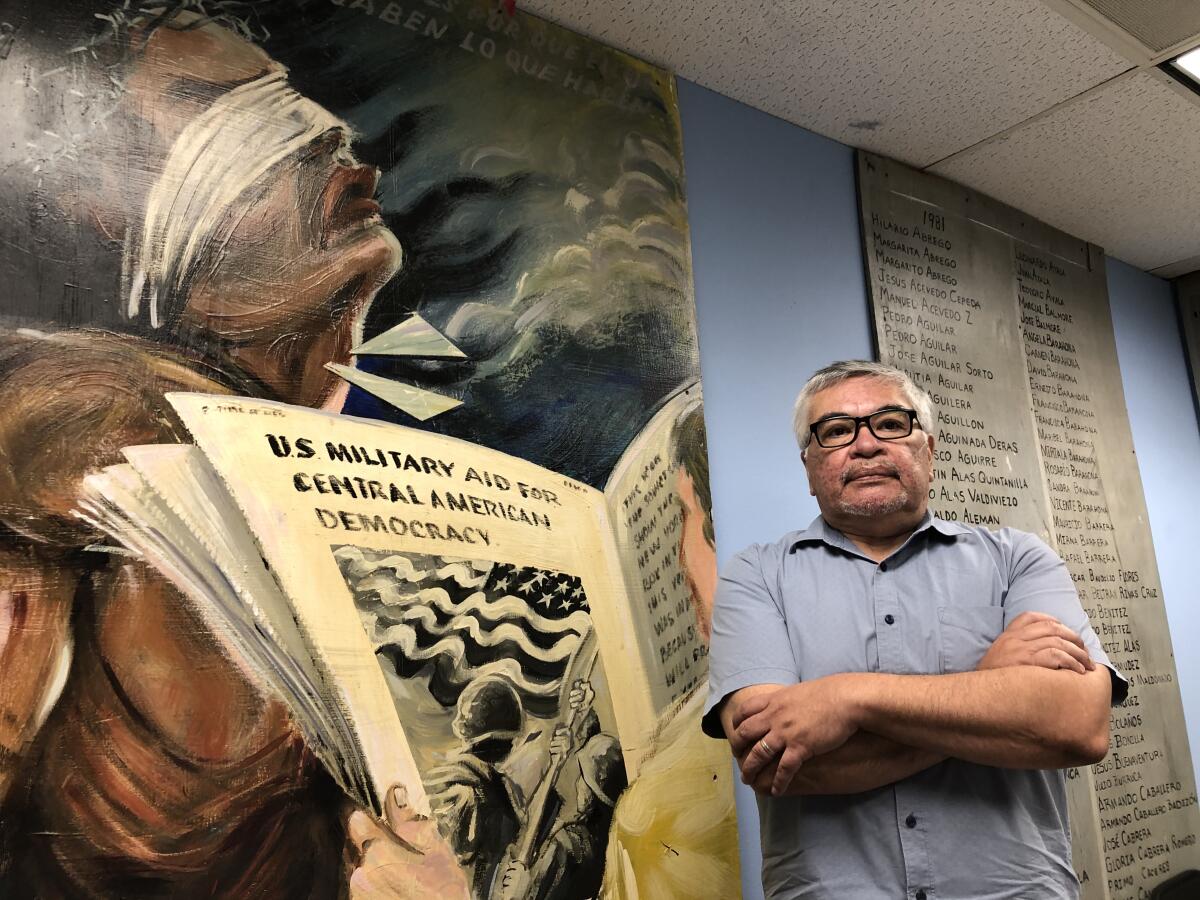

Sanabria, now executive director of the immigrant rights organization El Rescate, believes that President Trump’s stated refusal to accept unconditionally the outcome of next week’s election is inflaming the spirits of extremist groups.

“That is a hypocritical, demagogic and authoritarian position, when you only accept what is going to benefit you,” the activist said.

Omar Corletto, an economist, arrived in Los Angeles at the end of 1983. His father, who was kidnapped Usulután, El Salvador, was among the 8,000 Salvadorans who disappeared during the 1980-92 war.

While some Americans are busily arming themselves to the teeth, Corletto has witnessed the consequences of violent civil unrest. “We know how sad it is and how it ruins the lives of future generations,” he said.

William Pérez, a professor of psychology and migration at Loyola Marymount University, said that threats of electoral violence are clearly being targeted at voters of color.

“Its primary purpose is to intimidate and prevent these populations from making their voices heard through the voting process,” Pérez said.

“That is the contemporary form of those repression processes that many of us in Central America have been escaping from their conflicts and governments,” added Pérez, who arrived from El Salvador in 1984.

Equally troubling, analysts say, is the way in which aggressive responses can escalate between aggrieved groups that fear and distrust each other.

Edna Sandoval, a UCLA student working on her master’s degree in Latin American studies, said Black and Latino communities that have pushed back against Trump administration policies on issues such as immigration and policing are being met with a stepped-up, increasingly hostile response from white supremacist groups.

“It is inevitable that violence occurs when there are people resisting,” said Sandoval, a native of Guatemala.

Miguel Tinker Salas, professor of Latin American studies at Pomona College, said the “historical trajectory” of the United States reveals recurring efforts to suppress minorities’ right to vote. This suppression is intensifying under Trump because the nation’s dwindling white majority feels threatened by the growing influence of people of color, he said.

Non-Latino white people “reject the notion that the United States is not the bastion of an Anglo-Saxon culture and, therefore, while that issue is on the table, I believe that this polarization continues and could become even more acute,” Tinker Salas said.

The current U.S. situation reminds activist Mario Avila of when the Guatemalan government and military suspected any person who identified with popular movements as being in league with leftist guerrillas. He was targeted for organizing agricultural workers who grew corn, coffee, jocote, tangerines and oranges, among other products.

“The fact that you were organizing the population put you inside that insurgent box,” said the Izabal native who left for Mexico in 1980, before arriving in Los Angeles in 1990. Ávila, 76, survived two rounds of torture, in 1969 and 1976, suffering electric shocks, cigarette burns and being held underwater.

On a recent hot afternoon in L.A.’s Westlake neighborhood, Waykan, the businessman, was working his second job at a warehouse filled with disposable plates, Mayan costumes and imported foods. He also works as a translator in the federal courts.

Waykan, 49, speaks the Q’anjob’al language of his ancestors, and thanks to his command of Spanish and English he has served as a translator for his monolingual compatriots since 1998. The Guatemalan, a native of Huehuetenango, emigrated after he was attacked by one of the paramilitary groups that operated during the war under the orders of the army.

“Right now just mentioning it makes my heart race,” said Waykan, who in 2018 became a naturalized American after a long process of political asylum.

The intimidation that is swarming now in the United States, Waykan said, is something that the inhabitants of Nanqultaq village, in the municipality of Santa Eulalia, lived with. The town’s roughly 1,000 residents were indigenous people who grew corn and cutting coffee.

In their village, they were in a crossfire between the guerrillas and the army. As an 18-year-old student leader, he was targeted by the military, which suspected such students of being potential guerrilla recruits.

One night in 1989 at a student event, seven armed men pushed their way in and struck Waykan with blows and stomps.

“I only remember that they kicked me and several came to hit me,” he recalled about the incident that left him unconscious.

Shortly after that beating, he left Guatemala. At first, he had a grudge and a thirst for revenge. Today, he relives the trauma when memories are shaken loose.

On Nov. 3, he will vote in a U.S. presidential election for the first time.

He plans to cast his ballot in person, at a voting center.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.