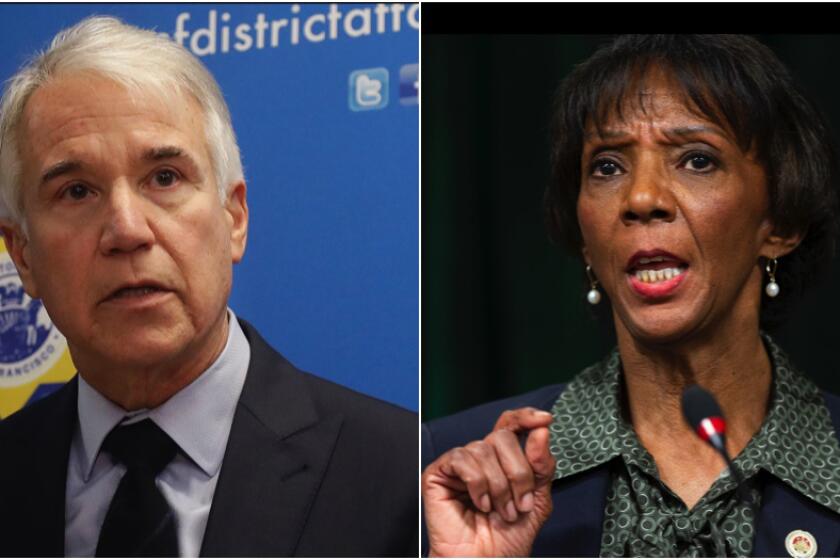

Law enforcement reform roils L.A. County supervisor race

L.A. City Councilman Herb Wesson was early into his bid for a seat on the Board of Supervisors when the endorsements and donations from law enforcement started flowing in. The biggest prize: $500,000 from the union that represents a majority of county sheriff’s deputies.

But that was all before the police killing of George Floyd in late May and a spate of local police shootings that prompted protests and renewed calls for increased police oversight.

The law enforcement endorsements, initially celebrated by Wesson, have now put him on the defensive as his opponent, state Sen. Holly Mitchell, tries to gain ground in a close race that has the two veteran politicians scrambling for a powerful seat long held by Black politicians.

The candidates are vying to replace term-limited Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas in the 2nd Supervisorial District, a swath of the county from Culver City to Carson that represents 2 million people, including a growing Latino population and about half the county’s Black residents.

In a district with high rates of unemployment and poverty, issues of affordable housing, access to healthcare and better paying jobs loom large in any race, but this year’s civil unrest and growing calls for police reforms have reshaped the campaigns in surprising ways.

Both candidates have scrambled for key endorsements from Black Lives Matter leaders and other activist groups and big-name politicians, hoping to edge ahead in a contest that will hinge, in part, on the two leaders’ records on criminal justice issues.

Wesson has hit back against Mitchell, pointing out that she too has accepted donations from law enforcement unions in previous campaigns. Mitchell, however, has taken a “no cash from cops” pledge in this race and argued that past contributions never stopped her from introducing legislation they didn’t support.

Such endorsements have long been routine among “all stripes of candidates” and rarely made a difference, said Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a political analyst and longtime L.A. community activist.

“But post-Floyd, it is an issue with some who feel that this endorsement signals a much too cozy relationship with the sheriffs who are under intense fire for abuse and misconduct,” Hutchinson said.

The candidates’ profiles cut across gender and generational lines.

Mitchell, 56, came to politics in 2010 after leading a large L.A. child and family care organization, and she is known among her peers in the Legislature as an astute anti-poverty policymaker.

A mother of an adult son, Mitchell had a big break in the Senate five years ago when she stood up to her fellow Democrats, arguing their budget failed to appropriately serve poor Californians.

Wesson, 68, has held public office for 22 years, most recently on the Los Angeles City Council.

A father of four, including one son experiencing homelessness, Wesson is known as a savvy negotiator who pushed for multiple increases in the city’s minimum wage but has been dogged by accusations that he gives in easily to special interests, including real estate developers.

While Wesson was serving as council president, the FBI launched a corruption investigation into City Hall, which focused largely on Councilman Jose Huizar, who faces charges of bribery and money laundering, and whom Wesson once called his “best friend” on the 15-member council.

Wesson has not faced allegations. In January 2019, his chief of staff was included in an FBI search warrant seeking evidence for its investigation but has not been publicly accused of any wrongdoing.

Mitchell has highlighted the corruption scandal in her TV ads.

“When he continues to talk about and remind us that he was the leader of the council and all that power afforded him to do, one has to wonder,” Mitchell said in an interview.

Wesson, who has distanced himself from Huizar, said his reputation should not be questioned because of Huizar’s alleged crimes.

“I am disgusted by what occurred, and no matter what we do it is virtually impossible to legislate integrity,” Wesson said, saying he had no idea what Huizar did.

In a district filled with service industry and essential workers, the government’s response to the pandemic has driven some of the campaigning. Wesson has run ads showing himself handing out food and supplies to residents hit hard by COVID-19. The supplies — some of which were handed out in yellow bags with Wesson’s name, others in boxes with his name on them — include 500,000 diapers, 1 million pounds of food and 40,000 masks, some of which were branded with his name.

In one of these ads his campaign tries to paint a contrast between the candidates: that Wesson has been helping people during the pandemic while Mitchell has been at home.

Mitchell called this a “false narrative,” noting that she has provided direct action, such as free coronavirus testing and masks to child-care workers, but that she had a bigger impact helping to craft a budget that avoided teacher layoffs and big cuts to social service programs.

Mitchell has focused her most aggressive attacks on Wesson’s political ties with law enforcement organizations.

She has criticized Wesson for siding with the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union that represents almost 10,000 rank-and-file LAPD officers, on a ballot measure that passed in 2017 that created an all-civilian board to oversee disciplinary cases involving officers.

Black Lives Matter, the American Civil Liberties Union and other justice and civil rights groups opposed the measure, Charter Amendment C, arguing that civilians are generally more lenient on problem officers.

Wesson said in an interview that he wished he had gathered more community input before proposing the measure but that his intention was to address the lack of diversity among hearing officers who assessed police misconduct.

The measure, Wesson said, improved police oversight and, though it isn’t perfect, brought some change to a bad system.

“I brought people together, and I got everything out of this that I could,” Wesson said. “I am not afraid and have never been afraid to sit up, look law enforcement in the eyeballs and say, ‘No, you got to do it this way.’”

Mitchell and her supporters say she has been a champion of criminal justice reform during her 10 years at the state Legislature. She represents the 30th Senate District, which stretches from Century City to South L.A.

Among legislation that she has written is a law that reduces sentencing disparities between powder and crack cocaine and a law prohibiting grand juries in cases of deadly shootings by police.

Assemblywoman Sydney Kamlager (D-Los Angeles) credited Mitchell for taking significant criticism when she proposed legislation that limited law enforcement’s ability to permanently seize the property of suspects when they haven’t been convicted of a crime.

“In the meetings with law enforcement agencies, they were sticking their finger in her face and saying ‘Don’t do this,’ or ‘How dare you,’ and the types of microaggressions that happen when folks feel a Black woman shouldn’t be up in your business,” Kamlager said. “It was in those moments that she was like, ‘Absolutely I’m going to continue to fight.’”

Mitchell’s attacks appear to have scrambled Wesson’s campaign strategy.

This month, Wesson pulled his endorsement of L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey, who has been criticized by activists and is viewed as too cozy with police compared with her more progressive challenger, George Gascón.

Wesson has responded to the attacks by accusing Mitchell of being hypocritical. He said Mitchell also sought the sheriff’s union endorsement for this campaign — as it’s customary for supervisor candidates to present their platforms to each union representing county workers. Wesson also said the sheriff’s union did not give directly to his campaign but instead donated to an independent expenditure committee supporting his supervisorial bid.

The November contest between Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón to oversee the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office has been framed as a test of appetites for criminal justice reform.

One of Wesson’s ads highlights three $1,000 donations that Mitchell received during previous reelection campaigns from CoreCivic, a private prison company that also runs ICE detention facilities. Formerly Corrections Corporation of America, the company has given millions to Republicans and Democrats, including Wesson when he was in the Assembly.

Although both have pulled in big-name endorsements — including both receiving an endorsement by Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) — arguably the most notable are their endorsements from Black Lives Matter leaders.

In February, Mitchell received an endorsement from Black Lives Matter co-founder and executive director Patrisse Cullors.

On Oct. 1, Wesson snagged his own key endorsement from a Black Lives Matter leader when Melina Abdullah, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, pledged her support.

The endorsement surprised some community activists. Longtime South L.A. activist Najee Ali, who decided last week to endorse Mitchell, said he has seen a “tremendous shift” in Wesson’s politics over the last few months.

“And his recent rescindment of his Jackie Lacey endorsement, he is only trying to appease progressives, and it’s pandering,” Ali said.

But Abdullah says this is not so.

Although Wesson and Black Lives Matter have “absolutely not” agreed on things in the past, he has always told them the truth and never gone back on a commitment, Abdullah said. He has also been supportive of the People’s Budget, a policy initiative advanced by activists that would divert significant money from the police budget into social services.

“We’re in a really great position that nobody is terrible,” Abdullah said, referencing her respect for Mitchell. “I think that Herb Wesson’s long-standing commitment to the community, his willingness to really engage in a democratic process that brings everybody in, where there’s ongoing conversations — and he’s been willing to even engage those who are critical of him — I think that speaks volumes.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti, who has known Wesson for about 20 years, said it is “absolutely wrong” to suggest Wesson hasn’t been committed to racial justice.

When Garcetti became mayor, he saw that Wesson was one of the first people trying to build bridges between the city and Black Lives Matter, setting up meetings between then-LAPD Chief Charlie Beck and Abdullah.

Although Wesson probably has more name recognition, both candidates have long histories of serving the region, said Dermot Givens, political analyst and executive director of BlackMenVoting.com.

Givens said his sense is that the district’s Black population will be mostly split between Mitchell and Wesson. “Now, where do get the rest of your votes?”

The race will probably be close, he said.

“They will be the most powerful African American politician in California and will be able to build a legacy from that,” Givens said, “because their endorsements [of others] and putting people in positions is going to be absolutely tremendous, and they’re going to have 12 years to do it.”

Times staff writers David Zahniser and Melanie Mason contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.