California teacher unions fight calls to reopen schools

As parents express widespread dissatisfaction with distance learning, two influential California teachers unions are pushing against growing momentum to reopen schools in many communities, saying that campuses are not yet safe enough amid the pandemic.

Leaders with the California Teachers Assn., with 300,000 members, and United Teachers Los Angeles, representing 30,000 in the state’s largest school district, said that districts do not have the resources to provide the level of protection they say is needed to bring teachers and children together in classrooms.

“Our teachers want to be in front of the students,” said E. Toby Boyd, president of the California Teachers Assn. “We can’t do it unless it’s safe.”

Their stance carries weight in the coming weeks and months as teachers’ working conditions are part of union-negotiated contracts. Unions and districts need to return to bargaining tables to work out new schedules, classroom arrangements and workloads under the safety guidelines for operating in-person classes during the pandemic.

Boyd acknowledged that 100% safety is impossible, while suggesting that teachers and their union leaders are in the best position to determine what is safe enough.

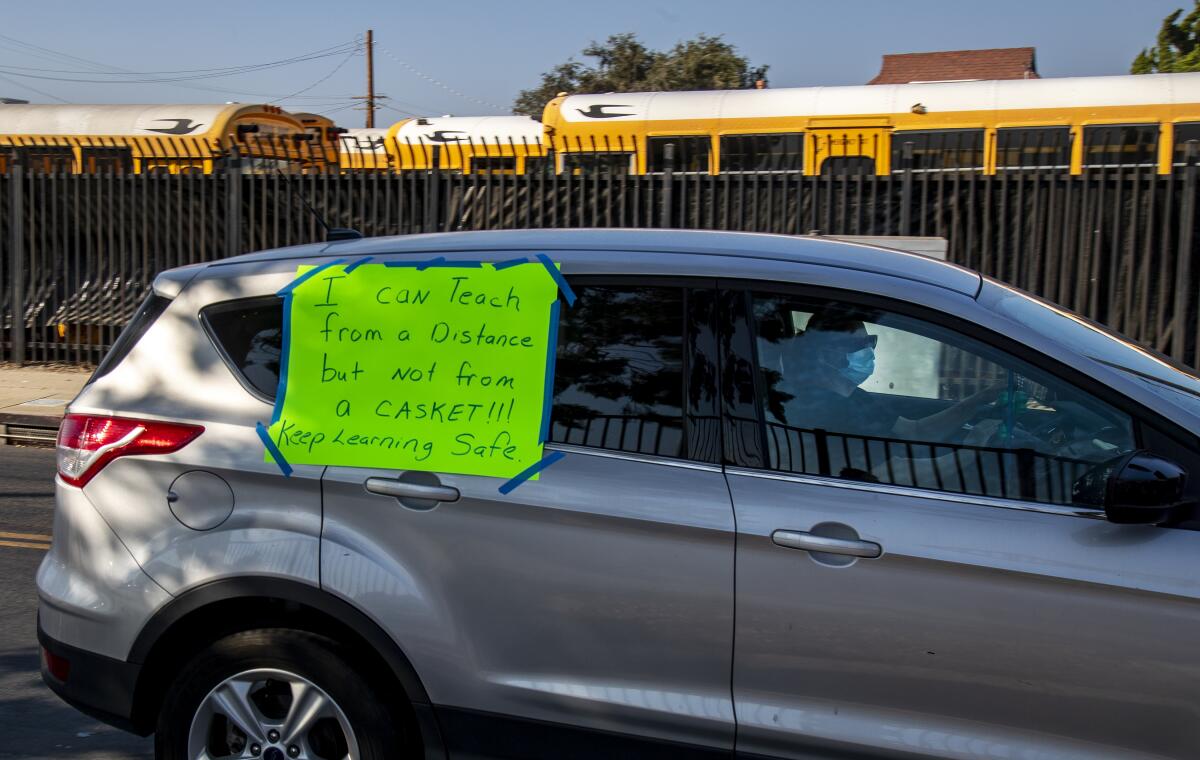

In Los Angeles, union participants in a news conference Thursday at Dorsey High School in South L.A. spoke out against calls to speed up the pace of reopening because the district’s high-poverty communities have been hard-hit by COVID-19 and because infection rates remain high. About 80% of district students are from low-income families.

“We cannot allow a rushed or careless reopening of schools that will once again disproportionately impact students and families of color because of unsafe conditions at their schools,” said Sharonne Hapuarachy, an English teacher at Dorsey.

Union organizers also opposed a piecemeal, school-by-school reopening, especially because that would favor more prosperous neighborhoods, where COVID-19 is less prevalent.

“We need to know that students in East L.A. will be just as safe returning to school as students in West L.A.” Hapuarachy said.

Critics of the unions point to research that suggests the unions’ positions are too extreme.

“More and more research is showing that reopening schools will not overly endanger students and staff,” said Lance Izumi, senior director of the Center for Education at the Pacific Research Institute. Izumi cited research from Brown University suggesting that “schools are not super spreaders and school infection rates are low even in places with high community rates.”

Separately, researchers at Yale concluded that child care could be offered with relative safety.

Currently, no schools can fully reopen in Los Angeles County because of widespread virus transmission, according to state guidelines. But school systems can offer in-person, one-on-one tutoring and assessments and bring back small groups of students with special needs, including students with disabilities and students learning English.

United Teachers Los Angeles has reached an agreement over one-on-one tutoring that allows teachers to volunteer for the work. But the union opposes the return of small groups of students until further safety protocols can be negotiated. Some other nearby school systems are moving more swiftly to bring back small groups. A campus is allowed to bring in up to 10% of enrollment at a time for services to these students.

The timing of the union response Thursday signals the teachers’ concern that reopening momentum is gaining the upper hand amid the push and pull of politics, evolving science, incomplete data and frustration over distance learning.

On Tuesday, L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger questioned a senior health official about why it was taking so long for schools to open in L.A. County. Some school and district officials also have pressed the issue, noting that infection rates in their communities are low. Advocacy groups, including some newly formed by parents, also have called for campuses to reopen — or to at least serve more students with special needs.

A poll commissioned by the research and advocacy group Education Trust — West found that parents think less of distance learning than they did in March, even though most students are now connected online and most experts agree that districts have upped their online game. Still, 35% of parents rated online learning as successful compared with 57% in March. Low-income parents are more likely to rate online learning as unsuccessful.

The survey was conducted among 800 parents of children in California public schools from Oct. 1 through 7, with a confidence interval of plus or minus 3.4 percentage points and adjusted for geographic and demographic accuracy.

The poll also found that more than two-thirds of parents report higher stress levels for their children in school. And just over half of parents say they would like more in-person learning for their child than what is currently planned.

But the flip side is that many parents are not so eager to rush their children back to campus, which was a focus of a CTA poll.

The CTA poll also found widespread discontent with distance learning and an array of opinions on whether district officials are moving too fast or too slow to reopen campuses: 46% of parents said their local district was moving at about the right pace; 25% too fast; 22% too slow; 7% were not sure.

In this poll, 62% of parents said they were not comfortable with sending their children back to school when surveyed from Sept. 18 to 25. Four in 10 voters and parents said campuses should not reopen for in-person instruction until there is a vaccine. Pollsters interviewed 1,296 registered voters in California with a sample that allowed for breaking out the views of parents with a margin of error of plus or minus 3 percentage points.

All but 10 of California’s 58 counties can now reopen campuses provided that they follow extensive protocols, according to the California Department of Education. These 10 counties, which have 35.6% of California students, include Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties in Southern California and Monterey and Sonoma counties to the north.

However, not all eligible districts have chosen to reopen, including Santa Ana Unified in Orange County and San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest school system. Long Beach Unified, the second-largest district in L.A. County, has announced that it won’t fully open campuses before January.

L.A. Unified, the nation’s second-largest school system, hasn’t ruled out reopening sooner but has trailed some nearby school systems in bringing back small groups of students with special needs, which is allowed in any county — in part because of union resistance.

Frustration over lack of services for her child with special needs prompted parent Erica Meyrich-Pinciss to move from an L.A. Unified school to one in Hermosa Beach.

Because L.A. Unified is offering no in-class instruction, Meyrich-Pinciss’ son attended his first few weeks of transitional kindergarten through Zoom. But there were constant technical problems, Meyrich-Pinciss said, and the teacher spent most of the day playing YouTube videos for the class of students with multiple disabilities.

She said her son was bored and seemed to be regressing.

Alicia Baltazar, a single parent of a fifth-grader at Friese Avenue Elementary School, said she doesn’t believe L.A. Unified has enough financial resources to carry out necessary safety precautions.

As someone who is immunocompromised, Baltazar feels like her life is in LAUSD’s hands.

“Our campuses don’t even have a nurse every day of the week,” she said. “So how can you tell me it’s safe to send my kid to school during a pandemic?”

At Dorsey High School, groups allied with UTLA presented “minimum conditions for reopening ... centered on racial justice.”

The demands included a call for additional cleaning staff and a maximum classroom size of 12 students at a time. State rules require physical distancing or barriers when this is impossible but do not specify the class size once schools are allowed to fully reopen.

Some of the demands are in accord with what L.A. Unified officials insist they are trying to accomplish — including comprehensive testing and contract tracing, but points of difference are expected to emerge at the negotiating table.

One clear point at both events was a call for more funding.

Current funding levels for schools were based on the presumption that more federal aid would be forthcoming. Without it, funding cuts are looming.

“Our response to this unprecedented pandemic cannot be budget cuts and business as usual. There is no plan in Sacramento to increase funding for our schools,” said Lester Garcia, political director for Local 99 of Service Employees International Union, which represents most non-teaching workers in L.A. Unified.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.