The Los Angeles Times tested first-class U.S. Postal Service delivery. The results? Spotty at best, dismal at worst.

The letter — filled with stickers for a 5-year-old boy named William — was mailed at the post office in the Los Angeles community of Sylmar on Aug. 22. It was sent first class, at a cost of 55 cents, and with a promise, according to the U.S. Postal Service website, of “delivery in 1-3 business days.”

The plain white envelope arrived at its destination, a ranch-style house in Austin, Texas, 11 days later.

Another letter, mailed from Malibu to the San Francisco suburb of Millbrae, sat in a Los Angeles processing center for three days and wasn’t delivered for an additional four days after that.

And a letter sent from the Alhambra post office to a residence in Washington, D.C., took four days to get to the mail processing center in the capital, and three more days elapsed before it reached its final destination.

The slow mail service from Los Angeles to cities near and far was just one of the findings of a Los Angeles Times effort to test, in a small but revealing way, the reliability of the Postal Service as it comes under increasing scrutiny due to deep cuts by the Trump administration.

The Times survey, which tracked 100 letters sent between Aug. 21 and 24 to multiple destinations within California and beyond, showed that postal performance in the summer of 2020 is spotty at best, dismal at worst.

There is no single snag in the complex postal delivery system. Instead, multiple choke points can slow a letter’s journey. In the worst cases, the postal system fails in more than one way.

The Times measured its letter delivery times against the advertised figure from the Postal Service, which says first-class letters should arrive at their destination in one to three business days. Gaare Davis, president of the American Postal Workers Union, California, said the Postal Service has had a goal of delivering first-class letters within the state in two business days and in three business days to Austin, Atlanta and Washington.

Among the findings:

• Half of the 20 letters sent to the San Francisco Bay Area arrived late, taking four to five business days to be delivered.

• Only about half of the 40 letters sent to Atlanta and Washington were marked as arriving on time. Ten arrived within four to five business days; eight were never marked in the Postal Service’s certified mail tracking system as delivered, although they did end up arriving at some point.

• One letter sent to Texas never arrived; another took eight business days to land, out of 20 letters sent to Austin.

• Overall, 75% of the letters sent by The Times that should have arrived within two business days actually arrived on time. This rate is substantially lower than the Postal Service’s most recent performance metric, which shows a 92.4% on-time delivery rate in April, May and June.

The Times survey found that it is possible for first-class mail to arrive far quicker than the official standards, but it didn’t happen all that often. Of the 60 letters sent to Texas and the East Coast, just 12 were scanned as arriving within three calendar days.

In response to questions about The Times’ findings, Postal Service spokeswoman Evelina Ramirez said in an email that the agency continues to “identify and address some ongoing service issues in certain areas.”

But she stressed that “service performance improved across all major mail categories in the weeks prior to Postmaster General [Louis] DeJoy’s testimony on Aug. 24, and this trend has continued through August, returning to early July levels.” Ramirez did not respond to any specific finding and would not discuss whether the slow performances were related to the recent cutbacks.

But Davis called the findings “unacceptable” and said they should be brought to the attention of Congress, particularly to the House Oversight Committee, which grilled DeJoy on Aug. 24 about cost-cutting measures that led to current postal delays.

The changes in service have left customers waiting for prescription drugs and landlords waiting for rent checks, and created chaos in the Los Angeles processing center.

Accounts from employees at California postal facilities provide a glimpse of the chaos amid both the pandemic and widespread cuts imposed by the USPS.

DeJoy “is the current problem,” Davis said. “He took the [sorting] machines out. If the mail was running fine before he took over and before COVID, what’s the problem now? It sure ain’t the employees. The employees are doing their jobs with the tools provided.”

DeJoy, a major donor to President Trump, started as postmaster general in mid-June. The Postal Service, starting in July, dismantled sorting machines, slashed employee overtime pay and began strictly enforcing truck schedules, which workers say caused further disruptions.

The ensuing uproar caused DeJoy on Aug. 18 to say he would suspend some of the operational changes until after the presidential election, but he also said the cutbacks would not be restored.

DeJoy has acknowledged significant slowdowns in service. “We had some delays in the mail,” he said in Senate testimony on Aug. 21. “Our recovery process in this should have been a few days, and it’s amounted to be a few weeks.”

But he also vowed that the possible flood of mail-in ballots — an expected increase tied to fears of standing in long lines during the COVID-19 pandemic — will be handled appropriately.

“As we head into the election season, I want to assure this committee and the American public that the Postal Service is fully capable and committed to delivering the nation’s election mail securely and on time,” he said. “This sacred duty is my No. 1 priority between now and election day.”

The degradation of first-class mail is not exactly a new phenomenon; California has lost more processing plants than any other state between about 2006 and 2012, said Phil Warlick, the union’s legislative director.

In 2015, the Postal Service changed its first-class service mail standards so that most mail once delivered overnight is now delivered in two days. That shift largely ended the overnight first-class mail delivery service once enjoyed by people sending letters within the same metro region.

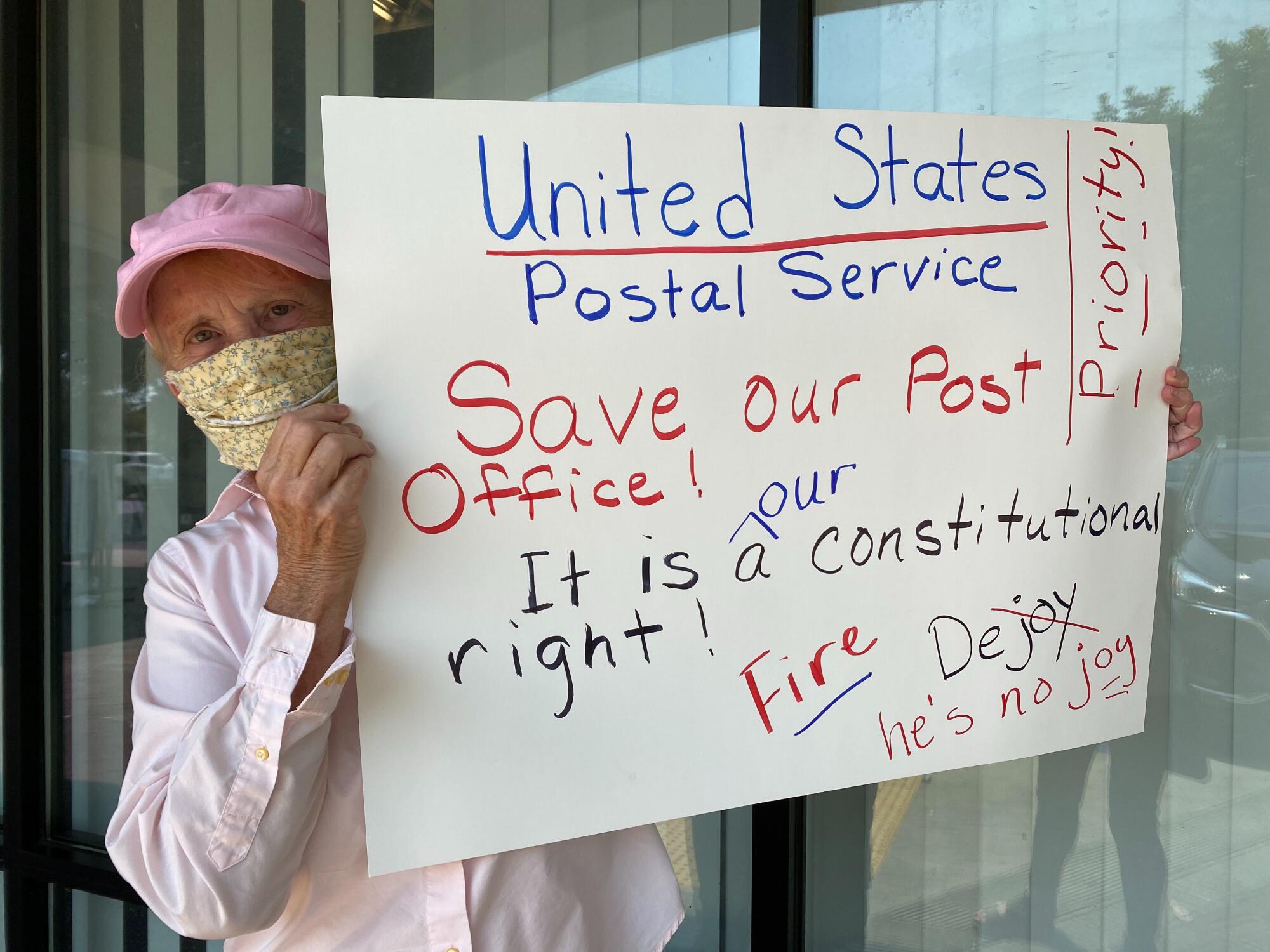

The worsening delays worry Ola Steenhagen, a 74-year-old from Porter Ranch who was protesting in front of the Granada Hills post office on Aug. 22, waving a sign that said, “Save our Post Office!”

It was a Saturday, the same day the House held a rare weekend session and voted to block Postal Service changes and give the beleaguered agency $25 billion. Trump tweeted that the measure was a “money wasting HOAX.”

Steenhagen’s husband is a veteran who receives his medication in the mail. Inhalers that help him breathe have been arriving weeks late. The couple vote by mail and are worried about the effect of postal problems on the coming election.

“I’m worried about everybody,” she said. “I’m worried about the farmworkers, the people who might be able to vote and won’t have the services to mail their vote. And their kids who can vote, but it’s not easy.”

Critical prescriptions are being delayed, placing many Americans’ health in jeopardy. New credit cards, rent checks, stimulus payments from the Internal Revenue Service — all have been stalled.

This is how The Times’ survey worked: From Aug. 21, when DeJoy was grilled by a Senate committee, to Aug. 24, when he testified before the House, The Times mailed 100 letters to five destinations.

The first-class letters were sent from 20 post offices all around Los Angeles County, from Lancaster in the north to Long Beach in the south, from as far west as Malibu to as far east as Pomona. They were sent from pricey spots, such as Beverly Hills, and from Boyle Heights, a working-class Eastside neighborhood with high poverty rates.

The destinations included Arcadia, in the San Gabriel Valley northeast of downtown Los Angeles; Millbrae; Austin; Atlanta; and Washington, D.C.

Among the bottlenecks The Times’ survey revealed were inexplicably long travel times, lengthy waits at the processing center in the destination city and unexplained stretches of time between leaving that facility and landing in the recipient’s mailbox.

None of the departure neighborhoods in Los Angeles County had dramatically different levels of service; mail sent from Compton fared about the same as that sent from Pasadena.

Three distribution centers that process outgoing mail for L.A. County also had no systemic delays in sorting departing letters, according to The Times’ survey. Of the letters sent to the Bay Area, most spent less than three hours in the sorting facilities in Los Angeles, Santa Clarita and Santa Ana.

But arrival cities are a different story entirely. Mail delivered to Washington took markedly longer to arrive than that sent to Austin or Atlanta.

The processing center that serves the Washington, area was a destination bottleneck. The three letters The Times sent that lingered longest between destination processing center and final recipient were all headed to a residence in the capital.

It took three days for all three letters to get from the Washington processing center to the residence, even though it was just one mile away.

Letters sent to Millbrae were slowed by multiple choke points in the system: one during the time in transit, another at the destination processing center in San Francisco, and a third at the local post office.

In one vivid example illustrating the slow California service, it took nearly three times as long for a letter mailed in Malibu to reach the San Francisco distribution center as it took for a letter mailed in Pomona to reach the distribution center in Washington.

The Postal Service can be speedy. Seven of the 20 letters sent from Los Angeles County to the residence in Millbrae arrived within two calendar days. These envelopes spent only about four hours at the sorting facility in San Francisco.

However, just as many letters took a full week to make that same trip. The transit time alone between L.A. County and the Bay Area was between 2½ and 4½ days for a drive that takes less than seven hours in traffic that’s coronavirus-light.

The letters then spent between one and four days at the San Francisco sorting facility before being sent to the post office in Millbrae.

There was still one more stop. And at this point, the journey got even stranger.

Most of the slowest letters were marked as out for delivery and en route to their final destination at 8:36 a.m. on Aug. 27.

But it took them more than a day to get from the Millbrae post office to a residence within the tiny city, which is less than four square miles in size, arriving on Aug. 28 at 10:05 a.m.

The distance? Just a quarter-mile.

About 1,400 feet.

A five-minute walk.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.