For L.A. Latinos, Whittier Boulevard is still a crossroads of change and hope

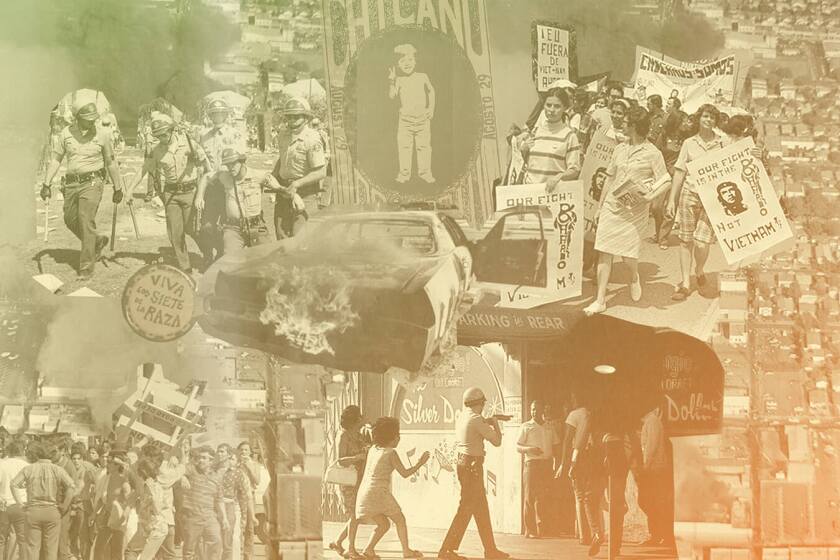

Fifty years ago, a coalition of Mexican American activists solidified a landmark East L.A. thoroughfare as the epicenter of the Chicano movement.

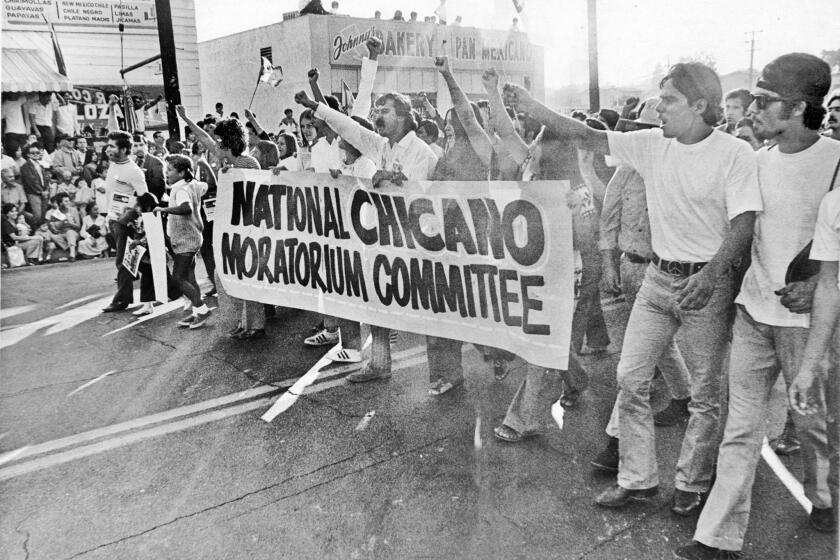

On Aug. 29, 1970, thousands of people, some from as far as San Francisco and San Diego, gathered to march down the core shopping area of Whittier Boulevard to push for Latino civil rights and denounce the Vietnam War machine, which was being powered with thousands of Black and Mexican American bodies.

For decades, the boulevard had served as a hub of Latino life, commerce and culture. It was an affordable shopping district for an emerging, immigrant-rich middle class that had been redlined out of other neighborhoods. It was a teen hangout where rival Garfield and Roosevelt students gathered after football games to split a soda at A&W Root Beer, snog at drive-in theaters or catch Little Richard shrieking ecstatically at Sebby’s, on the corner of Whittier and Soto Street.

Some spent the week detailing their classic cars and bicycles. Come Friday night, throngs of lowriders cruised the boulevard, blasting Chicano soul.

“Let’s take a trip down Whittier Boulevard!” “¡Arriba, Arriba!” shouts local act Thee Midniters before ripping into “Whittier Boulevard,” their 1965 surf-guitar-driven instrumental tribute to East L.A.’s main street mythos.

“I’m from La Habra, and we had family connections in East L.A. and Montebello and Pico, and driving back and forth [on] Whittier Boulevard was not just a commute or a daily practice, but it was literally what connected us across space and time,” said Jerry González, associate professor of history at the University of Texas at San Antonio and director of the UTSA Mexico Center.

Then suddenly, in the spasm of one late-summer afternoon, Whittier Boulevard took on yet another layer of identity — as a space for political action.

The historic Chicano Moratorium march began as a celebration of community pride and solidarity but ended with sheriff’s deputies beating protesters while buildings went up in flames. Eastside native Frank Villalobos, a 23-year-old recent graduate of Cal Poly Pomona, was among those bearing witness a half-century ago. He remembers the shuttered and shattered storefronts, the police raining tear gas on the crowd, and local merchants handing him a Dixie cup filled with water to stay hydrated during the march.

50 years ago, the Chicano Moratorium made an indelible impact on L.A. culture and civil rights. Explore the LA Times project.

“I wasn’t one of the guys in front, but one of the participants running down the street with everyone else,” says Villalobos, 74, president of the nonprofit Barrio Planners, an Eastside architectural firm.

But the demonstration did more than sharpen the community’s political conscience, Villalobos said. It also marked a new evolutionary stage for the boulevard, which has constantly reinvented itself while adapting to a changing Los Angeles: surviving economic blight and violent street-gang clashes, refurbishing its central business area in the late 1980s, enduring as a cultural hub of Latino L.A.

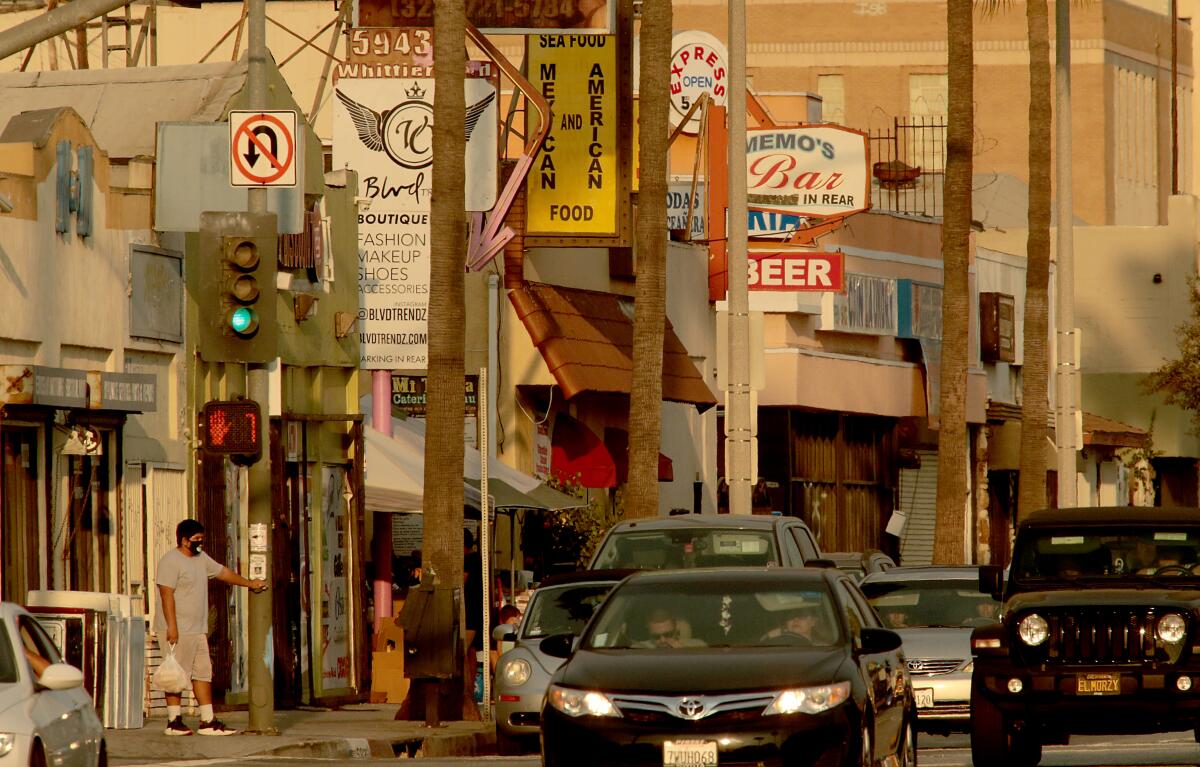

Today, the heart of 14-mile Whittier Boulevard, from Eastern Avenue on the west to Atlantic Boulevard on the east, is facing a new host of challenges — including the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic meltdown, as well as creeping gentrification. But for many, this faded but resilient avenue remains an axis of change and hope.

“The street is an icon,” Villalobos said. “It seems dead right now because of COVID. But Whittier Boulevard is really a survivor of all the things that happened in the past.”

From East L.A. into the peripheral cities of Orange County, the boulevard’s character shifts with the changing demographic landscape.

But the main shopping corridor between Eastern and Atlantic has made Whittier Boulevard a community rallying point in good times and bad — such as the present moment. According to the L.A. Times’ coronavirus tracker, East L.A. had the most confirmed COVID-19 cases in L.A. County with 5,617 as of Aug. 27. The toll on Whittier’s main commercial strip has been ominous.

This slice of the boulevard was nearly vacant on a recent afternoon except for a few families walking down the street. Scores of mom-and-pop shops were closed, barred with black steel gates. A few already have gone out of business, and more casualties of the economic downturn are likely to follow in coming months. Foot traffic has fallen drastically.

Inside a First Communion store, near Kern Avenue and Whittier Boulevard, a mother and son gazed at the fluffy white dresses displayed along the wall behind giant Plexiglas. Farther east, a couple perused a shop whose mishmash of baby clothes, toilet paper and party supplies spilled onto the sidewalk. Across the street, a group of five older men wearing surgical masks congregated in front of a liquor store before dispersing to catch the 720 Metro Rapid bus.

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, the boulevard for decades hadn’t received sufficient attention from “the powers that be,” said Tony DeMarco, a pawn shop owner and president of the Whittier Boulevard Merchants Assn., a collective of about 250 businesses along the drag. As an unincorporated enclave of Los Angeles County, East L.A. never has fully shared in the region’s prosperity or resources, many residents believe. Few long-standing shops that were around even before the Chicano Moratorium remain.

“We’re all struggling. I don’t know how many will be back,” said DeMarco, who estimates that his business has dropped 60% during the pandemic.

Other ongoing problems have kept the boulevard from reaching its full potential, DeMarco suggested. He laments the lack of new commercial investment, a shortage of parking structures, and the way that a glut of unlicensed sidewalk vendors has hurt established restaurants and caricatured the neighborhood. When the L.A. Times writes an article about East L.A., he said, “it shows a picture of a poor immigrant pushing the cart.”

Gentrification also has taken a toll on the community. Those fortunate to have purchased homes more than two decades ago have seen their property values increase by an average of $338,910 within the 90022 ZIP Code, according to data from Zillow. But for the average East Los Angeles resident, who generally rents and earns a median annual income of $43,879, home ownership is out of reach.

Many businesses along Whittier have not been spared as mom-and-pop retailers — furniture stores, shoe shops and hardware stores — have been replaced by corporate giants such as Nike.

“All the businesses have changed over time,” said James Wenger, third-generation owner of Wenger Furniture and Appliances, whose current neighbors include a barbershop, a church, a Nike store and a cafe.

Established in 1947 on the corner of South McBride Avenue and Whittier Boulevard, Wenger Furniture joined a cluster of family business at a time when the boulevard served as the main commercial center for a growing Latino middle class. “I think we’re the last business left that’s been here from the ’40s and ’50s,” Wenger said.

The street’s current challenges contrast with its lofty past.

Historians contend that the boulevard had been part of El Camino Real, the “Royal Road” or “King’s Highway,” and was used by Spanish missionaries during the colonial period. The roadway area remained undeveloped for decades, surrounded by agriculture, until nearby industrial jobs prompted real estate companies to establish housing tracts.

“It was, like, the [crummy] part of town because the river would flood over there, so it was like, ‘Let’s let the Mexicans and the Chinese and the Jews, they can all live in that part,’” said artist Al Guerrero Jr., who grew up on South Kern, half a block south of the boulevard. Gradually, many Jewish and Asian people moved away, and the area became overwhelmingly Chicano.

Cities such as Montebello, Pico Rivera, Whittier, La Habra and Brea — all of which are carved by Whittier Boulevard — began as exclusively white communities but have grown to become Latino and Mexican American neighborhoods, according to González, the University of Texas professor. Pico Rivera made the quickest leap, with 90% of its population identifying as Hispanic or Latino, with Montebello not far behind with 78%, according to 2018 U.S. Census data.

In the decades before and after World War II, Whittier became a shopping district and, later still, a teenage oasis centered around cruising culture.

“Cruising is free, you just need money for gas,” said Luis Nuño, Cal State L.A. assistant professor of sociology. “It’s not going out to Disneyland or going to a place where you have to spend money.”

At that time, major retailers, movie theaters, dress shops, record stores and restaurants thrived in the densely populated, somewhat insular community. Many residents’ first language was Spanish; their U.S.-born children sometimes were reprimanded for not speaking English in school.

Back in the day, Guerrero recalled, East L.A. was a “homogenous community” that felt somewhat protected from white-majority Los Angeles, a place where you were “not exposed to direct discrimination or racism on a day-to-day basis.” When he went with his father to L.A., he could sense strangers’ suspicious, hostile stares.

Families didn’t need to travel far to get the essentials. Garfield and Roosevelt high schools were only a few miles away. JonSons Markets employed folks from the neighborhood. A Número Uno market recently took its place as the community grocery store. Teens worked summer jobs at Thrifty, movie theaters or the family business.

Wenger, 58, started working at his family’s furniture store when he was about 8. During lunch breaks, his family always would go out to eat at new restaurants, but Marcel and Jeanne’s French Cafe was his favorite for their soups.

Wenger also remembers helping his dad board up the store’s windows with wooden panels to prevent damage during the 1970 demonstration.

Several other marches were held throughout 1970, but the one in August left a bittersweet feeling. What started out as a festive and peaceful protest of about 20,000 attendees quickly turned into a fury of chaos when the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department intervened.

Businesses were set ablaze, scores were injured and arrested, and Times columnist Rubén Salazar was killed when a deputy fired a tear gas canister into a bar, striking his skull.

He was no radical. He was a prophetic reporter.

The demonstration helped bring Mexican Americans together politically and culturally, but perceptions of the protest and its aftermath, particularly among outsiders, also tainted the area.

A 1970 anti-war protest is remembered for the death of newsman Ruben Salazar. But far more happened the day 20,000 people spoke up for Mexican American rights.

The boulevard deteriorated economically and visually. It gained the reputation of a “war zone”; police erected barricades between Atlantic Boulevard and Eastern Avenue every weekend night to stop lowrider cruising. Feeling pushed out, many Latinos started taking their business to rival commercial centers in Montebello and to Pacific Boulevard in Huntington Park, which featured major chains such as JCPenney.

Villalobos, the architect, contends this also led to the annexation of a portion of the boulevard to neighboring City of Commerce, which he said later made it almost impossible for East Los Angeles to push for its own separate cityhood.

Merchants along the commercial hub grasped the seriousness of the moratorium. They realized that the demonstrators embodied their clientele, spurring a desire among the business folk to cooperate more with each other.

They banded together to fight for their deteriorating street. In the late 1970s, they started connecting with then-L.A. County Supervisor Ed Edelman and, later, Supervisor Gloria Molina, to beautify the area and boost its comeback.

In the 1980s, merchants tapped into their own savings and secured funding from state and county officials to help refurbish the boulevard with sidewalk and building improvements, Mexican fan palm trees, a Latino Walk of Fame and, their pride and joy, a 65-foot-long arch centerpiece displaying the boulevard’s name.

Locals flocked to the revived boulevard for the annual Christmas parade, featuring celebrities and local officials. Merchants implemented a robust graffiti removal program and hung seasonal lights and banners during the holidays.

We’re “a community that tries to revitalize itself all the time,” Wenger said. He believes that adding major retailers such as Apple could help beef up the boulevard. “We are constantly trying to grow.”

But for others, humble mom-and-pops that know their customers by name also must retain a place in the boulevard’s future.

Connie Molina, 27, remembers frequenting the area with her family when she was in high school. They would board the 18 or 720 bus to catch a movie or play at the arcade. Molina said she’d visit a clothing boutique to get an outfit for a Friday night backyard party.

Now the small-business owner said she visits the area only to buy baking supplies and groceries from her neighborhood’s Número Uno market. She reminisces about the boulevard’s Chicano history, but her memories of bustling arcades and packed movie houses are fading.

“It’s nowhere near alive as it used to be,” she said.

The boulevard’s roots aren’t forgotten, it’s just “there are so many things going on in this world,” said Carlos Cortez. The 20-year-old recently has made a habit of visiting the area every Sunday with his girlfriend and baby to sell his homemade lemonade raspados from his makeshift cart. He appreciates the area’s rich history — “There’s a lot of Chicano roots that are still there” — but thinks it’s time for a new generation to reinvent the boulevard once again.

“When we think about changes in the landscape, a lot of folks will reference the Whittier Boulevard of their time. At the same time, somebody is making new memories of their time,” said González, the San Antonio professor.

“Its significance for the future of the Latinx community is still there. It’s going to be central to not only how L.A., but how this country, reckons with these really horrific practices against Latino immigrants, Mexicanos and Mexican Americans, because it’s always been there.”

For Guerrero, the evolving boulevard remains part of the “fabric of his childhood.” He doesn’t plan to abandon it anytime soon despite more possible changes on the horizon. Now a West Adams resident, he feels the old, fond memories return whenever he revisits East L.A and the boulevard. “I can walk around here and Karens are not going to look at me.” He no longer recognizes parts of it, he said, “but I can still connect to the spirit of it.”

He regularly makes the drive from his West Adams home to walk the street and grab a bite to eat at his favorite childhood restaurant, Porky’s, for its carne deshebrada burrito drenched in “picoso but flavorful” red sauce.

And he waits for new sights and new sounds to revive the old memories.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.