‘A forgotten city’: An L.A. community beset by police violence and crime hopes for change

Denise Nelson remembers when her Westmont neighborhood wasn’t filled with liquor stores, storefront churches and abandoned buildings.

There used to be a theater across the street from her bargain store near Imperial Highway and Vermont Avenue. The area was once home to a roller skating rink and thriving Black-owned businesses.

Recent years have brought hard luck to the small South L.A. community of nearly 34,000 people wedged between the city of Los Angeles and Inglewood. This week, Dijon Kizzee, 29, was shot and killed by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, sparking protests and national headlines decrying excessive use of force against Black people, including George Floyd, Jacob Blake and Breonna Taylor.

On May 26, another man was shot by sheriff’s deputies on the same street as Kizzee. Deputies fired 19 rounds at Robert Avitia, 18, who was a suspect in a killing and had a handgun, authorities told coroner investigators.

Residents in the area say they fear street violence and the potential for violence perpetrated by authorities. Their struggles are compounded by a decades-long lack of investment and resources, and the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic that has disproportionately affected Black and brown communities.

“It’s like a forgotten city,” said Kevin “Twin” Orange, a longtime gang intervention worker who was born and raised in Westmont. “All we got is candles where people have been killed at, abandoned buildings and motels and liquor stores.”

Recently, there’s been a string of violence in the area. Alan Snipes, 42, was found on a sidewalk with gunshot wounds the morning of Aug. 4. On June 30, Derek Wilson, 61, was killed in his car. Two days earlier, Lorenzo Hall Jr., 27, and William Lay, 31, were shot hours apart.

Kizzee was on a bike when he was flagged down for what the Sheriff’s Department said was a vehicle code violation. Kizzee dropped his bicycle and ran. Deputies shot him after Kizzee dropped a jacket he was carrying and made “a motion toward” a gun that fell to the ground, sheriff’s officials said.

People who witnessed the killing said deputies kept firing at Kizzee after he collapsed to the ground. His family said he was a family-oriented man.

On a recent afternoon, Gregory Brown and two friends sat outside an apartment building to relax after a long day of work. A breeze blew through the neighborhood as other residents sat on their porches, talking to one another.

Brown said he’s frustrated not only by the violence but years of injustice and the economic disadvantages that Black people have faced for hundreds of years.

“We survived the ‘80s, we went through that,” Brown said. “But now you got this pandemic and now you got the police you have to watch out for at the same time.”

Brown tries to set an example for his two sons. He votes because he wants them to vote when they grow up.

“It’s the only way to change things,” he said.

The median household income in Westmont — whose residents are 44% Black and 53% Latino — is lower than other areas of South L.A. and the county as a whole, according to census figures. Only 6% of residents hold a bachelor’s degree. In a 2018 L.A. County Department of Public Health report examining community disparities, Westmont ranked as one of the lowest in the county for life expectancy.

“There’s just structural and historical abandonment,” said Alejandro Villalpando, a professor of Pan African and Latin American Studies at Cal State L.A. who grew up in the neighborhood and lives nearby.

Villalpando recounted as a youth walking to Washington Preparatory High School to prepare for an SAT test and witnessing a shooting. At 19, sheriff’s deputies pulled their guns on him while he was riding his bike in the neighborhood.

Villalpando said at the heart of the problem is a lack of investment in recreation programs and mental health services, and what he calls “active disinvestment” in the community.

“People aren’t born to be shooting at people at 7 in the morning,” Villalpando said. “That’s not the order of things.”

Kala Patterson, a social worker at Westmont Counseling Center who runs a group for women, said people in the neighborhood experience structural racism, poverty and violence on a daily basis.

“They’ve learned to function in a state of trauma,” she said. Patterson said she’s used to hearing ambulance sirens and the hum of helicopters during sessions.

“You hear it every single day,” she said.

In recent years, there have been efforts to reinvest in the area. Plans are in place to redevelop a stretch of land near Vermont and Manchester avenues that has sat vacant since the 1992 civil unrest with a shopping center, boarding school for at-risk youth and affordable housing. A homeless shelter is scheduled to be built near the sheriff’s station. And the Public Health Department has also launched an initiative to help stem violence and trauma.

“We can’t let the community give up on itself,” said Mark Ridley-Thomas, a county supervisor whose district includes Westmont. Besides the other efforts, his office has also planted trees and is working to build a small park.

“We’ve gone in and tried to make a number of things happen,” he said.

Los Angeles Sheriff’s Capt. Duane Allen said before this year, the area had seen a record low number of shootings before a surge this summer. Budget cuts in the department slashed additional summer patrols and a youth program.

“We don’t have extra people to engage the community,” Allen said.

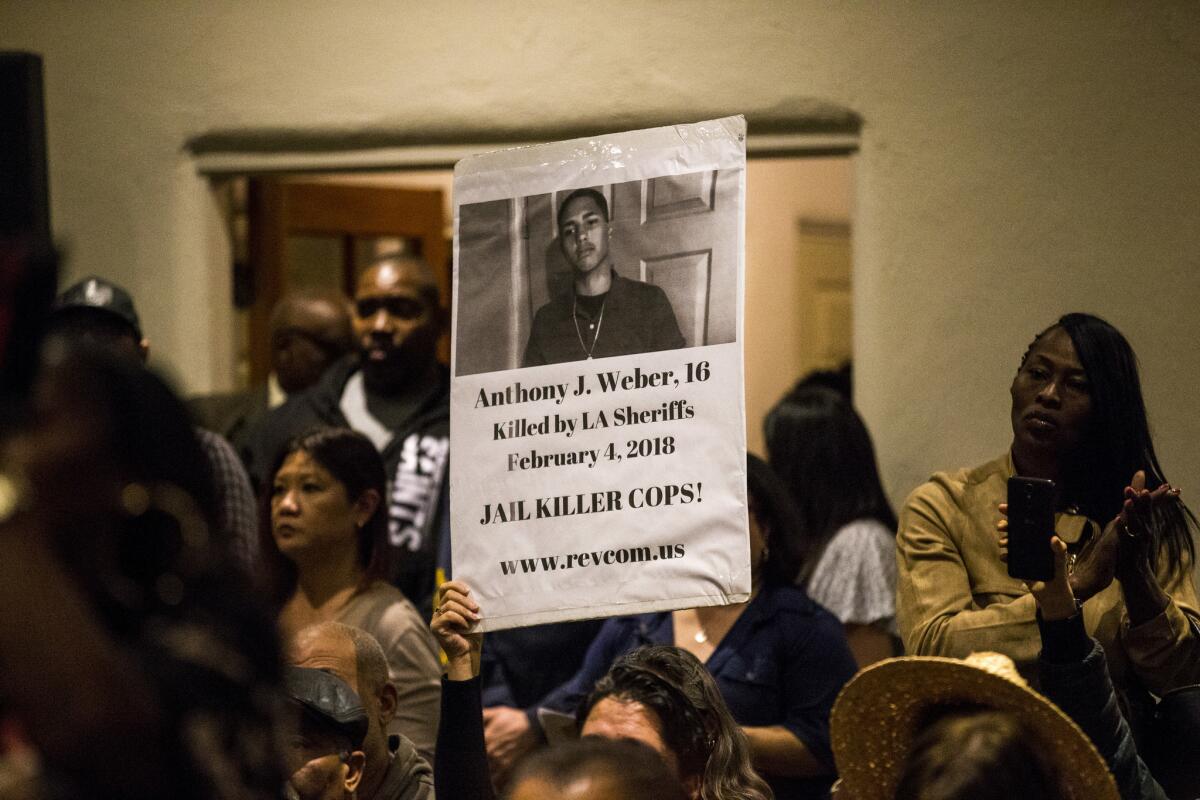

Demetra Johnson, whose son Anthony Weber, 16, was shot and killed by deputies in 2018 in the neighborhood, said the changes haven’t come soon enough. Relations between the Sheriff’s Department and community are tense, she said.

That much was visible on a wall and building not far from where Kizzee was killed. Graffiti spelled out expletives and the word “sheriffs” was crossed out.

When Kizzee was killed this week, Johnson joined other demonstrators in a march to the South Los Angeles sheriff’s station. She said Kizzee was a patron at the market she runs.

“It’s just heartbreaking,” she said of another police shooting in the neighborhood she’s called home since 1983.

Johnson worries about her 14-year-old son. She says she’s lucky that he prefers playing video games to going outside to play.

When Alani Snipes, a 22-year-old mother of two, saw signs in the area listing local landmarks such as Los Angeles Southwest College, she was disheartened: The streets are in need of repairs. Schools lack decent equipment.

It felt, Snipes said, as if officials are pretending that crime, murder and police killings are not occurring in the area.

“The things that truly matter are not given the time and effort as they should,” she said.

Snipes, who lives near the sheriff’s station, said she thought her proximity to law enforcement meant safety. Last month, her father, Allan Snipes, was killed while on a morning walk.

The shooting of Kizzee left her thinking that police officers need better training. Police reform is needed, she said, and it’s an issue that must be spearheaded by local officials.

“You have to nourish the people in order to nourish the city and they don’t see that,” she said.

Nelson, who owns Connaisseur’s Bargain Store in Westmont, is working to improve conditions. She runs A Step Above Your Vision, a nonprofit that provides transitional housing and life skills to homeless people. She mentors young women in the area.

She wants to add a juice bar and sandwich shop in her store. Her dream is to one day open up a homeless shelter and resource center next door.

Her goals are an attempt to bring something to the community she thinks is needed: a message of hope.

“I’m trying to be a good example for people,” she said. “I’m trying to show what they can do.”

Times staff writer Sandhya Kambhampati contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.