Latino students advance, only to fail

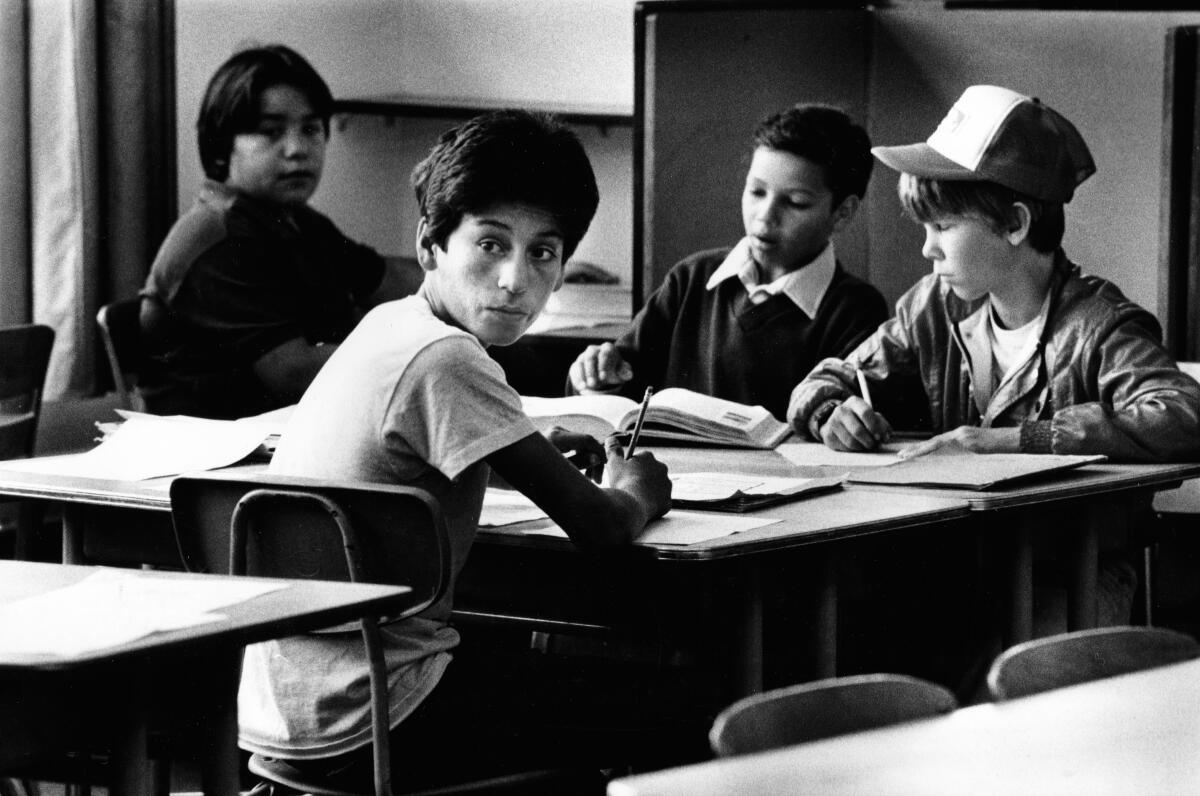

A wiry, bright-eyed 13-year-old, Ernie Perez seems no different from most other seventh-graders at Killingsworth Junior High School in Hawaiian Gardens. He appears well-adjusted to school life, attentive, tries hard and rarely misses classes.

But Ernie is caught between two worlds. His friends speak English and his classes are conducted in English. At home, he is faced with parents who speak only Spanish.

Unfortunately, Ernie, who was born in Torrance, does not have a good command of English and speaks virtually no Spanish.

Frequently lost and confused, Ernie sometimes has to resort to sign language to communicate with his Mexican-born parents, who have two years of formal education between them.

His home life of mixed messages and crossed signals carries over to school. Ernie’s Cs and Ds show it. His proficiency test scores show that he already is two grade levels behind his Anglo classmates.

Researchers say that Ernie is a classic example of the under achieving Latino student in California’s public schools, and that there are thousands more like him.

Ernie’s dream is to be a professional athlete. Although he is slight of build, he is already noted for his football and basketball exploits at Killingsworth. But at this point, he is a prime candidate to drop out. Even if he finishes high school, school officials fear that Ernie will graduate with no more than the equivalent of a ninth-grade education.

::

The problem for Ernie Perez and others like him is that most are failing through the educational cracks. Educators say these children have traditionally been neglected and often are regarded by teachers as uncaring failures.

Many schools assess the language skills of these students and wrongly assume that they have no special needs because they are more fluent in English than in Spanish, according to researchers.

In fact, these underachievers represent one of California’s most serious educational challenges, state Deputy Supt. Of Public Instruction Pete Meza said.

Generally speaking, there are significant differences in achievement between Anglo and Latino students by third grade, according to Robert A. Cervantes, an administrator with the state’s Office of Migrant Education.

By junior high, the achievement of Latino students as a group lags behind Anglos by 2 to 2 ½ grade levels, and by high school, the gap is 2 ½ to 4 grade levels, Cervantes said.

“In effect, the longer Hispanics stay in school, the further behind they fall,” Cervantes said.

Because they are more proficient in English than Spanish, the vast majority of these underachievers do not qualify for bilingual programs.

But their language difficulties are only part of the problem. Low expectations on the part of teachers and administrators also play a significant role, according to researchers.

Latinos in School: Why Do Many Fail?

Latino children too often seem destined to fail from the first day they enter school. Here is a brief primer on the situation:

The students – Latinos make up 25% of public school enrollment statewide, and 49% of enrollment in Los Angeles city schools.

The state Department of Education reports that of the 1,045,000 Latino students statewide, about 23% are performing satisfactorily—at or near grade level. Another 31% are not proficient in English and are considered below grade level until they acquire English. Most of these are in bilingual programs. The remaining 46% are classified as English speakers but their achievement is unsatisfactory—below grade level. Robert A. Cervantes, an administrator with the state Office of Migrant Education, said youngsters in this group account for much of the high Latino dropout rate.

Dropout rate – The state Department of Education calculates the Latino dropout rate in secondary schools at 45% over the last 12 years.

Cervantes estimated that, on average, 39,195 Latino students have dropped out each year during that period. That, he added, is more than the total number of Latinos who graduated from California high schools last year—38,698.

“The waste of human potential is self-evident,” Cervantes said.

Achievement – State Department of Education studies show that, in general, Latino students repeat grades at twice the rate of Anglo students. Twice as many Latinos read below their grade level, compared to Anglo students.

Expectations – On the learning potential of Latino students, John Goodlad, dean of the Graduate School of Education at UCLA, declared: “I think there is a growing acceptance of Hispanics being able to learn. But for too long, they have been kept in lower (academic) tracks where the subject matter taught to them was not sufficient to prepare them for college or science and high technology. The same idea existed for black children, and they’re very capable of learning. We have to overcome this idea that Hispanic children can’t learn.”

::

Thomas P. Carter, a professor at California State University, Sacramento, has been studying Latino education in California for almost 25 years. Carter said that educators for too long “have set their expectations level for teaching Latinos at too low a level. They don’t expect much and, lo and behold, they don’t get much.”

Latinos are often seen as the products of a culture of poverty, Cervantes said, leading to the creation of a new vocabulary among educators to explain why so many Latino children do not do well.

The descriptives tagged on these children, Cervantes said, include such labels as “apathetic, fatalistic, non-goal-oriented, unacculturated and culturally deprived . . . disruptive, withdrawn, not working at full potential, truants, lacking in self-esteem, rebellious and frustrated.”

Along with language problems and low expectations, Cervantes adds these factors as crucial to understanding Latino underachievement: segregation, unequal educational opportunities and discriminatory school practices, high absenteeism, an excessive dropout rate, overrepresentation in low-ability groups and in so-called special-education classes, and insensitivity among educators to the Latino culture.

The advancement — or non-advancement — of Latinos in the larger society has paralleled their record in the schools. That there are so few Latino doctors, attorneys, engineers, teachers and corporate managers can be traced directly to the painfully slow progress of Latinos in California elementary and secondary schools.

::

Nadine Barreto, principal at Killings worth Junior High, recalled an incident when Ernie Perez first enrolled at the school. A high-strung, restless boy, Ernie had a difficult time settling into classes, so Barreto scheduled a conference with Ernie, his mother and sister, Sally.

Barreto said the discussion was conducted entirely in Spanish. She had assumed that Ernie also spoke Spanish, the sandy-haired boy responded, “I don’t know what you’re saying.”

Startled at first, Barreto said she then realized that Ernie was typical of many other students she has seen during her teaching career.

And even though Ernie is an English speaker, Barreto said it was clear that “his sentence patterns were not good. He was basically dysfunctional in both languages.”

The same thing occurred when a Times reporter interviewed Ernie’s parents at their home in the barrio of Hawaiian Gardens in southern Los Angeles County.

His parents, especially his mother, Paula, talked about her visions of her son going to college for the education that she and her husband never got while growing up in Mexico. Paula Perez has only two years of formal education; Ernie’s stepfather, Ignacio, an unemployed welder, never went to school.

They live in a Spanish-speaking world and have no need to learn English. They, as do other Latino parents in similar situations, leave that to their children, who can translate for them if the need arises.

“I want him to finish school, maybe go to college. I don’t want him to fail,” Paula Perez said in Spanish, looking at her son, who appeared bewildered during the interview.

Although Ernie said he understood some of the interview, he was clearly at a loss as to what was being said about him. He mostly smiled politely when he heard his name, or turned his head when he heard words and phrases familiar to him.

Asked if he understood what was being said, Ernie first looked at his parents and then shrugged: “Not much. A little I can understand, but not much.”

Ernie seems too innocent to detect the biting frustration that his mother feels because she cannot converse with him as well as she does with six older children and her 9-year-old-son, Abel.

She said they have attempted to teach Ernie Spanish, but “it doesn’t stick with him.” She continued:

“Maybe he doesn’t want to learn Spanish. His eyes get big when we speak Spanish to him. I know I gave asked him to get something and he’ll bring me back something totally different.”

Nonetheless, they keep trying. They tell him to stay away from local street gangs, to study hard in school and to come home before dark. But the best they can hope for is that Ernie will understand some of their guiding words.

So how did Ernie become and English speaker in a family where Spanish is the dominant language?

According to his mother, Ernie learned much of his English from his sisters, Sally, 19, and Margaret, 17. The two sisters spoke to him mainly in English during his first years in school. When he could not understand his mother’s Spanish, Sally or Margaret would interpret for him.

But when Sally and Margaret married and moved away, Ernie was left in a linguistic lurch. And even though Sally lives down the street and regularly helps him with his homework, the only person he can speak with at home now is Abel, his 9-year-old brother who enrolled in bilingual classes at Furgeson Elementary School, also in Hawaiian Gardens.

On a recent report card, Ernie got three Ds, two Cs and one B. the word on him, according to Barreto is that he “has a lot of untapped potential.” His work and study habits are good, and his teachers, recognizing that he needs help, have given him more individual attention.

But whether Ernie will be able to close the gape between himself and his Anglo classmates is uncertain.

According to his test scored on the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills, Ernie’s academic performance appears to follow the classic pattern of the Latino underachiever.

In the first grade, Ernie tested about one grade level above national norms in reading and language. His math scores were 1.3 grade levels above national norms — so strong that they placed him in the top 20% of math achievers in his grade.

Educators say that math often is a Latino student’s strongest subject in the early years because language and verbal skills are no the barriers that they would be, say, in reading and writing. However, math courses get more difficult and so do the language barriers, teachers add.

Ernie’s scores began to drop slightly as a second-grader. In the third grade, he really took a nose dive. By the fourth grade, his records showed that he was already a full year behind in most subjects compared to many of his Anglo classmates.

By the sixth grade, Ernie’s once-promising math scores had fallen off, too. He was half a grade behind in math—a drop of almost two academic years since his first-grade scores.

::

Ed de Avila, a professor at Stanford University, can relate to the underachiever. A second-generation Mexican-American, De Avila grew up in East Los Angeles and was a city schools dropout.

And even though he ultimately earned a Ph.D. in education from Canada’s York University, De Avila still recalls the agony of being publicly ridiculed by teachers” because they thought I was dumb.” He remembers how depressing school was to him and countless others like him.

De Avila has been studying and writing about the academic achievement of Mexican-Americans for about 20 years.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

He said students such as Ernie may know more Spanish than they admit, or may be afraid or ashamed to use the language. Even so, the practical result is that they are unable to function comfortably in either Spanish or English.

Youngsters who are dysfunctional in the two languages, he said, often speak a unique “Spanglish”—a jumbled hybrid of Spanish and English that nonetheless can be used to communicate, especially in the barrio.

It is common, for example, for a barrio youngster to fashion sentences that include both English and Spanish (“Como fue school today?”) or to form seemingly Spanish words from English ones (“Donde esta su troque?”) using troque instead of the Spanish word for truck, camion.

De Avila said that when Latino youngsters take their hybrid English to school, they immediately begin experiencing structural problems with English, leading to insecurity, frustration and, ultimately, deep-rooted resentment.

De Avila said some teachers make matters worse by chastising the youngsters or channeling them into undemanding special programs that do little to correct such weaknesses.

Teachers who speak Spanish generally take a dim view of pidgin Spanish and can be just as rough on these youngsters as other teachers, De Avila said. Rather than empathizing with these students, De Avila says, many Spanish-speaking teachers are too quick to castigate them for poor Spanish usage.

“So they (underachievers) get it from both sides,” De Avila said. “No one likes to be corrected all the time. So their interest slips.”

Robert Cruz, president of the Nationals Assn. of Bilingual Educators, said there are instructive differences between U.S.-born Latinos and Hispanic students who immigrate here.

He said that many students from Mexico and Central and South America come here with positive attitudes and good self-esteem, and make the transition to all-English classes rather quickly.

The key, Cruz said, is that many of these immigrant children have benefited from formal schooling in their native country. With a solid academic foundation acquired in their native language, they are ready to make a successful transition to English, he said.

Cruz said, “They come and get English and their confidence level, which was already there, rises even more.

In contrast, Cruz said, the American-born Latino student goes to school speaking “Spanglish,” has low self-esteem, lacks role models and constantly hears negative expressions about his community.

“They’re told to go back to Mexico. ‘You’re nothing but a Mexican.’ It’s a very negative environment that they’ve grown up in,” Cruz said.

::

So, what can be done for underachievers such as Ernie Perez?

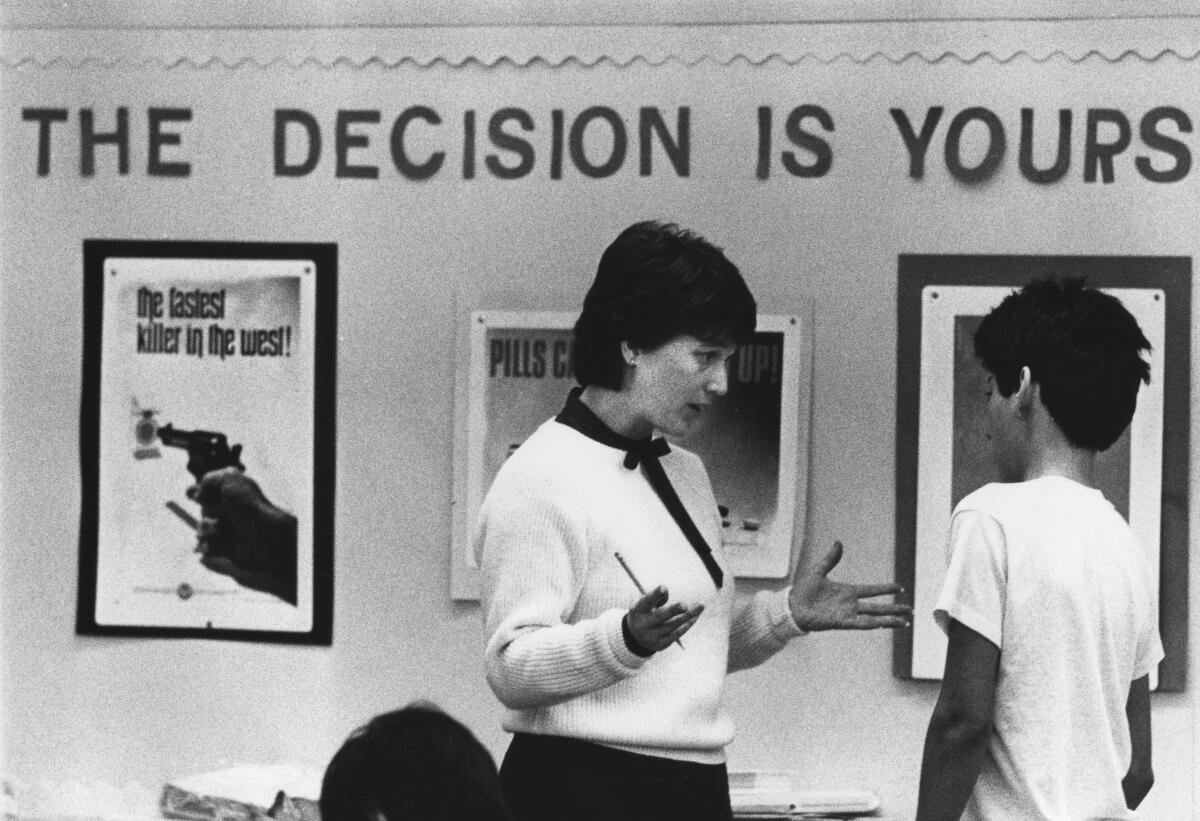

There is general agreement that educators must create an atmosphere of higher expectations for Latino students. But beyond that, there is uncertainty and disagreement.

Bilingual educators say underachievers should be placed in their programs for two reasons: They have the expertise to help such youngsters over the language barrier, and they understand the cultural ties and conflicts that the youngsters bring with them to school. However, state Deputy Supt. Meza is not sure that bilingual programs are the answer.

“My main reservation about bilingual education is its appropriateness as a treatment for the English-dominant Chicano kid,” Meza said.

“It’s (bilingual) a sound program where the kids are making a transition from another language to English. I really believe that the kids ought to be instructed in their home language until they learn English, that they don’t fall behind. I really believe in that concept.”

But Meza, who was named to his post by state Supt. Of Public Instruction Bill Honig, said he is afraid “we’re not serving a large group of kids,” adding:

“We’re making assumptions about what (the underachiever’s) needs are that may not be necessarily true. I’m not the only one that feels that. There’s a growing concern about the plight of the English-dominant Chicano kid . . . and a growing concern that we’re not looking at them as a unique population that needs to be served in a unique way.

“Most of our research has been focused on the needs of what we perceive to be the student in transition from Spanish to English or from another language to English (such as those in bilingual classes).

“But very little research has been done on that youngster who, on the surface at least, appears to have made the transition in terms of the command of the language, but yet continues to perform in school less well than other students.”

Cervantes of the state Office of Migrant Education said that some of these students probably do belong in bilingual classes, but he is undecided as to whether all do.

He said his “gut feeling” is to have a program for underachievers that would provide them with elements of a bilingual program. “But it would not be bilingual in the classical sense. Use teachers as language development specialists. But use people who know the language and who have (English as a Second Language) skills,” he said.

“You have to look at the whole ambiance of classroom content. The students need to relate to a curriculum that is understandable. I can see different approaches for different kids’ needs . . . .”

But at present, Cervantes admitted, “We don’t know what works.”

State and federal compensatory programs are supposed to address the needs of underachieving Hispanic students, but numerous educators interviewed by The Times said that these programs are not doing the job.

Cervantes and Carter, the Cal State Sacramento professor, contend that more than half the funds going into compensatory programs are used for teacher aides who are least likely to help underachieving students.

Stanford Professor De Avila said that the best results he has seen have been in classrooms where underachievers work cooperatively with each other.

“We put the kids through a lot of science and math. We’ve recognized the class and teach them to work cooperatively. We work it where the kids become responsible for their own learning,” he said.

“We’ve found out that the amount of time spent together is a strong predictor of their intellectual growth, more than the traditional notions of time on tasks on such things as ditto sheets.”

There are two social rules for De Avila’s classroom environment: One, you have the right to ask for help from anybody if you have difficulty; two, you have the responsibility to help if you are asked.

“We look at it like a factory,” De Avila said. “In a factory, no one person runs the whole show. There has to be a delegation of authority. So the children become responsible for their own behavior. Moreover, other children become their resources.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.