Four generations: Mexico to U.S. — a culture odyssey

Arcadio Yniguez was barely a teenager when he crossed the border into the United States in 1913. He came from Nochistlan, a town in central Mexico; like thousands of his countrymen, he was fleeing the violence of the Mexican revolution. Family legend later said that he had run horse for Pancho Villa at age 12 and even shared meals with the notorious revolutionary.

As Arcadio made his way north, he worked at odd jobs, tending cattle for a time at the huge King Ranch in Texas. H ended up in Chicago, where he met and married Guadalupe Salazar, another young immigrant from Mexico.

Their marriage lasted only a few years. Arcadio eventually returned to Nochistlan; Guadalupe caught a train to Los Angeles and took their only child with her.

From those modest beginnings came a remarkable family. Guadalupe, a strong-willed and resourceful woman, became the leader. Arcadio, despite his absence, remained a respected patriarch.

Over four generations, the family’s experiences have mirrored the history of Mexicans and their descendants in California. The people of this family have seen Mexican immigrants like themselves forcibly “repatriated,” their children punished for speaking Spanish and their sons sent off to war while anti-Mexican mobs rampaged through Los Angeles. But they have also helped organize a union for farm workers and joined in a Chicano political movement for equal opportunities.

And now, as Latinos have grown to one-fourth of the city’s population, most of the younger family members have moved from Los Angeles’ segregated barrios to the suburbs that their parents were not allowed to enter.

Today, the family is as diverse as the community it represents. In its ranks are high school drop outs, blue-collar workers and professionals. Most call themselves Mexican-Americans or Mexicanos; others prefer the term Chicanos or Latinos.

Arcadio has been dead eight years, but Guadalupe, 79, confined to a wheelchair by a stroke, remains the influential matriarch still intent on keeping the family together. It has not been easy.

Like other Mexican-Americans, Guadalupe’s descendants are caught between two opposing forces—the pressure to assimilate and the pull of ethnic identity and kinship with other Latinos. More than most ethnic groups, Mexican-Americans have managed to hang onto their culture while struggling for acceptance within the larger society.

But the pull-and-tug never ends: Guadalupe, who has learned English, stubbornly insists on speaking Spanish to her grandchildren, though few of them understand her.

In 1976, senior citizen clubs on the Eastside gave their “Mother of the Year” award to Guadalupe—mother of 6, grandmother of 28, great-grandmother of 10, respected elder of an extended family totaling more than 200.

In 1981, more than half a century after her arrival in the country, she became a U.S. citizen.

In many respects, Guadalupe and her family are the traditional American immigrant story. But there is a Mexican twist: With each new wave in the continuous immigration from Mexico, the story begins again.

Guadalupe sees recently arrived relatives from Mexico, retracing her family’s steps as they begin a new life in this country.

Mexicans, whose ancestors inhabited the Southwest long before the region became part of the United States, have strong feelings about this land. The Mexican immigrant does not have to cross an ocean. Only a line on the map separates two regions that once were one and that remain connected by longstanding familial, historical and cultural ties.

Thus, the journey of Guadalupe is as meaning today as it was 52 years ago when she and her 5-year-old son, Rudy, boarded a train bound for Los Angeles and an uncertain future

::

Watching open fields and cities race past her train window in 1931, Guadalupe wondered what it would be like to see her father again after more than 20 years.

Her last childhood memory of him was still etched in her mind: his hands tied behind his back. Being led away by federal soldiers to be pressed into military service during the Mexican revolution.

A few years later, her father joined the stream of Mexicans escaping the turmoil in their country and found his way to Los Angeles.

His countrymen’s cheap labor was welcomed in the fields and in the city. Mexicans laid rails across the Southwest and worked in massive construction projects in Southern California.

But they profited little from the development boom.

Housing was so overcrowded that some Mexicans lived in tent and shack colonies in central Los Angeles. They weren’t allowed to swim at some public beaches and were turned away from restaurants and schools.

By 1930, nearly 100,000 Mexicans lived in this rapidly developing city of 1.2 million. Six Spanish-language newspapers were published, but no political structure of any importance developed. Mexican government envoys stationed in Los Angeles were the most respected figures, and they kept community attention focused on the homeland.

Guadalupe’s first memory of Los Angeles is the palm trees. And she remembers being pleasantly surprised by the multitude of brown faces.

She went to work at a cannery, remarried and became active in the church and neighborhood social clubs. On weekends she and her family mingled with other Mexican immigrants at the downtown Olvera Street Plaza, a cultural and social center since the late 1700s, when Los Angeles was settled by Spain, before the city became part of Mexico.

And she was reunited with her father, Miguel Salazar. He had remarried and was living on the Eastside, earning $10 a week as a baker. With the money that he and his wife and 13 children earned each summer by picking fruit up and down the state, the family later was able to open a bakery on 1st Street.

Her father also was a strong union man. He participated in bakers union marches, part of an early burst of activity by unions with large Mexican-American memberships, from the fields to the garment factories.

Guadalupe and her second husband, Tiburcio Rivera, settled in East Los Angeles, near her father’s home, in an area still known as El Hoyo (The Hole). Tiburcio had been a band musician in Mexica and a pool-hall owner in Chicago, where he and Guadalupe met.

They began a family of their own (they raised five children, her son and their four daughters), and Tiburcio found work in an asbestos factory. One daughter remembers his returning home at the end of each day covered in white dust.

(The dust meant nothing to them at the time. But after 13 years in a sanitarium, Tiburcio died of tuberculosis, and the family later recalled that at least five of Tiburcio’s Mexican co-workers had died of the same disease.)

When the Great Depression came, Tiburcio lost his and Guadalupe made the rounds of churches in the neighborhood, begging for milk for her children. She worked as a house cook and was allowed to take some food home. She made clothes for the children out of empty sugar and flour sacks.

As the economy worsened, the unemployment rate among Mexicans exceeded that of the general population. But Mexicans found themselves accused of taking jobs for from American citizens. The U.S. government launched the Mexican repatriation movement, an event that Guadalupe remembers with distaste.

Thousands of Mexicans were loaded onto trains—the same trains many of them had helped build—and sent back to Mexico. Although exact records were not kept, scholars estimate that one of every three Mexicans living in the United States was deported—an estimated 500,000, many of them U.S. citizens.

“It was a terrible thing to see friends being moved out,” Guadalupe recalled. “Many people were forced to leave their homes and their belongings behind. It was sad. Some simply left notes with friends that they had to leave.”

Guadalupe’s countrymen did not protest. Nor did anyone else.

(Two decades later, Guadalupe saw a new generation of Mexican immigrants rounded up and sent back to Mexico during “Operation Wetback.” Border patrol agents roused families in their homes and tracked down others at schools and other public places. During a five-year period ending in 1955, an estimated 3.8 million deportations were recorded.

(In the 1960s, however, a new generation of Mexican-Americans began loudly protesting the government’s immigration and deportation policies. Today, many are protesting the Simpson-Mazzoli bills, seeping immigration legislation that many fear will again result in massive deportations and discrimination against Latinos.)

::

Guadalupe’s children remember growing up in a friendly community where paisanos (compatriots) gathered on weekends in backyards to share food and the latest gossip.

“It seemed like everybody we knew was a paisano. It felt like we were living in Mexico,” Guadalupe’s daughter, Ofelia, said. Years later, when she visited Mexico the first time, Ofelia already knew the names of flowers and trees, the smells and feel of Mexico, from stories her mother had told her.

The focus of young Ofelia’s world was the local Catholic and nearby mortuary on Brooklyn Avenue. “The big events in our neighborhood were weddings and funerals. Everybody took part,” she recalled.

Even then, East Los Angeles was a city within a city. Residents shopped at local stores and went outside the area only to work. “I had no concept of what existed beyond East Los Angeles,” Ofelia said.

Ofelia’s first contact with Anglos — anyone other than Mexicans — was at school. “School was a very separate life. It was us against them,” she recalled.

Mexican-American children were given demerits and kept after school for speaking Spanish. It was an experience that many remembered when they began raising families of their own. Ofelia’s generation, reprimanded at home for speaking English and punished at school for speaking Spanish, was determined to spare their children such anguish, and Spanish began to fade from their homes.

There were other discrepancies between the two worlds that, as a child, Ofelia could not reconcile: Why, at the lunch break, did Mexican children hide their homemade tacos and burritos under the table? Or why did an Anglo woman in the neighborhood call her a “dirty Mexican” when, in fact, Ofelia’s mother was a stickler for cleanliness?

But there were also friends to be made. Over a small hill behind Ofelia’s home lived the Esparza family and their 10 children. Ofelia used to get into rock fights with some of them. But when she asked the oldest, Amado, to the junior high school Sadie Hawkins dance, it was the beginning of a lifelong romance.

Amado and Ofelia, like other children in the neighborhood, attended Hammel Street Elementary, Belvedere Junior High and Garfield High schools.

Junior high was a “big new world” where Ofelia, always a bright student, remembers feeling insecure about competing with her Anglo classmates. She sensed that Mexican students were being treated unfairly. Pachuco-style short black skirts and pompadour hairdos popular among Mexican girls were ruled to be in violation of the school dress code. Ofelia and many of her friends became openly defiant.

Ofelia’s brother, Rudy Estrada Jr., also has vivid memories of that period. He had come to Los Angeles on the train with his mother in 1931, the only child of Guadalupe and Arcadio, who had used the name Rodolfo Estrada for an unexplained reason when they married. Shoeshine boy, errand boy and later slaughterhouse worker, he became the family’s main source of support when Guadalupe’s second husband was stricken with tuberculosis.

Remembering his child’s view of what lay ahead, Rudy said it never occurred to him to be a mailman or a white-collar worker.

“I thought those jobs are only for white people. If you’re Mexican, someday maybe you become a bricklayer or a janitor or something like that .... Or maybe a fighter. Yeah that was the escape. I knew a lot of them.”

Sports, in fact, became a tradition among the young males in Guadalupe’s family, and among the grandchildren there were several Garfield High School football stars.

When Rudy was growing up, the chief entertainment was partying with friends at someone’s home or going to the nearby swimming hole. Most other places were off limits to Mexicans, he recalled.

At the theaters, Mexicans and blacks were ushered upstairs or made to sit in the back. And at a public plunge, which Rudy visited only once, they were allowed in only on Wednesdays. On Thursdays, the water was changed.

Rudy’s brother-in-law, Amado Esparza, recalled driving with his teen-age friends east on Whittier Boulevard, “just to see how far we could go.”

In nearby Montebello, a predominantly white community at the time, police stopped them.

“They’d tell us, ‘You don’t belong here,’ and send us back to East L.A.”

“We lived in a glass bubble,” he said.

World War II would burst it.

::

In the country’s scramble to gear up for war, everyone’s labor was required, including that of Mexican-Americans. Even workers from Mexico who earlier had been the targets of massive deportations were once again welcomed. But there was a price to be paid.

Mexican-Americans died at a higher rate than any other group during World War II. And at home, anti-Mexican sentiment exploded into race riots in East Los Angeles during the summer of 1943, as sailors invaded the community to tangle with local youths in what came to be known as the “Zoot Suit Riots.”

Guadalupe, like other concerned parents, tried to keep her son, Rudy, off the streets. And she did not want him wearing the baggy pegged pants that the youths called “drapes” and the loose shirts and pointed shoes that characterized the pachuco style popular among young Mexican-Americans.

But Rudy saw the carloads of American servicemen who wheeled into East Los Angeles looking for the pachucos they called “zoot-suiters.” He was amazed at the viciousness of their attacks.

“At Jesusita’s (a neighbor), they pulled out her husband and one of the young kids—pulled them right out of their home—and beat the hell out of them,” he said. “And two of her sons were already fighting overseas . . . .”

Rudy recalled with some pride that Mexican-American gangs put their rivalries aside to join forces against the soldiers and sailors.

“When the gangs finally got together one day, boy, they kicked some ass,” he said, recalling one encounter where “there must have been 1,000 cars . . . . They had ropes and we had chains and jacks . . . .”

The 16-year-old boy did not understand what the fights were about, but years later Rudy concluded that “they were just racist . . . .Everywhere we went it was always, ‘Let’s get the Mexicans’ . . . . And the police just turned their back.

“They weren’t after just guys wearing zoot suits. They were after Mexicans. The newspapers substituted the name Mexican for zoot suits.

“Some of the same guys that were in those riots came home with Distinguished Service Crosses, Silver Stars, Bronze Stars and Purple Hearts that you could fill a bus with . . . .That’s what was so unreal, that’s what used to bug me. . . .If they treat me like that, what the hell am I doing here (fighting in the war)?”

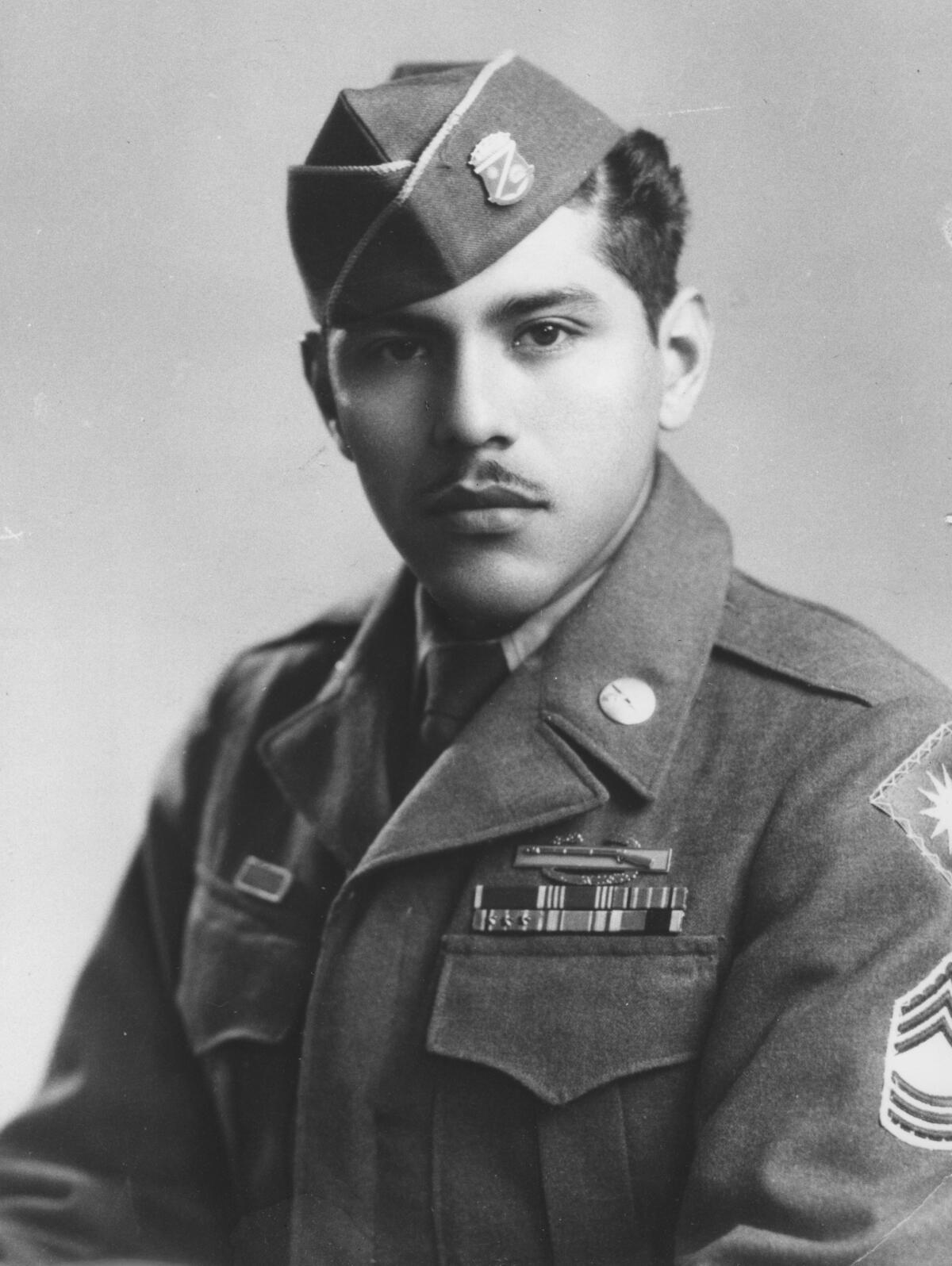

Rudy fought hard.

He was in four campaigns, including the Battle of the Bulge, where he was wounded in the right shoulder. He saw European cities in ruin and the grim remnants of Nazi atrocities at concentration camps.

Rudy earned a Purple Heart and Bronze and Silver stars. His father would probably have taken him out for a beer to celebrate.

Rudy had last seen Arcadio Yniguez in 1944, just after joining the service at 17. The family patriarch arrived unexpectedly in Los Angeles to talk to his son.

“He said that if I didn’t want to go in the Army, I could go to Mexico with him.

“I told him, ‘I don’t owe Mexico a damned thing. Everything I have and hope to be is in this country.’

“I think he was kind of proud of that answer. Then we went and had a beer.”

The military was a strong family tradition. Favorite family characters include Gen. Jose Ines Salazar, a colorful rebel leader who is said to have fought on various sides during the Mexican revolution, and a great-aunt, another revolutionary, said to have ridden a horse better than any man.

Years later, Vietnam tore at that tradition. But World War II was a landmark in Rudy’s life and the lives of an entire generation of Mexican-Americans, even with the pain brought many.

Rudy recalled a time when he and some Army buddies, traveling east with their outfit, were refused service at a San Antonio restaurant because they were “Mexican.”

Hurt and angry, he demanded of the waiter: “Does this look like a Mexican uniform?” But it didn’t help.

“Then we got to Mississippi and we found out that blacks couldn’t even walk on the sidewalk. We discovered just how bad it was.”

Back in East Los Angeles, one of Rudy’s aunts remembers the anxious walk home from work each day when she would glance at the banners on neighborhood windows, each indicating with a colored star whether a solider in the family had been wounded or killed.

“It was very sad because you knew all the families in the community and you knew who had died,” she said.

But there were good times too, and the walls that had separated Mexican-Americans from the outside world began to crumble.

Even Mexican-American women found well-paying jobs open to them in the shipyards and other defense plants.

Young couples ventured outside the barrio for the first time to socialize at the Cocoanut Grove and other popular ballrooms, where they danced to the big band sounds of Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller.

By the time the war ended, more than 300,000 Mexican-Americans had served in the armed forces. They became the country’s most decorated ethnic group.

They would no longer accept the old insult that Mexicans had heard for generations: “If you don’t like it here, go back to Mexico.”

They were Americans. They were not going back to Mexico, nor would they be confined to the isolated barrios where they had grown up.

“World War II opened up a lot of people’s eyes. We learned a lot,” Rudy said.

But if they had changed, often they found that things around them had not.

Rudy married his childhood sweetheart, and the couple set out to but a home with a GI loan, in Pico Rivera at a new housing development where he was a construction worker.

But a salesman told them that it was a “restricted” neighborhood.

“they didn’t want Mexicans in there and I was building the damned houses!” Rudy recalled. He chuckled at the memory, noting that Pico Rivera “is now all Mexican.”

But that day, Rudy was furious. He kept thinking about the war and what he and his Chicano friends had been through and about his two buddies who did not come back.

“it was racism. And it really hurt,” said Rudy, whose remarkably expressive dark eyes reflect a mixture of tenderness and toughness developed over years of battling open attacks on his dignity.

“Let’s get out of here,” Rudy’s young bride told him that day. “If they don’t want me here, I don’t want to buy a house in this lousy place.”

Many Mexican-American veterans shared Rudy’s outrage. Through organizations like the Community Service Organizations, the American GI Forum and the League of United Latin American Citizens, they began challenging restrictive housing covenants and other forms of discrimination.

Leaders like Rep. Edward Roybal (D-Los Angeles), who was elected to the Los Angeles City Council in 1949, merged from this World War II generation. Guadalupe was among those who walked door to door during his campaign.

A generation of Mexican-Americans began their move into the middle class, as higher-paying occupations began opening up to them. With the help of GI benefits, some entered college.

“When the war was over, we all got jobs, started going to school and buying homes,” Rudy recalled. “People got married and moved away to places like Montebello, West Covina, La Puente, Hacienda Heights, Alhambra. They built swimming pools and bought nice cars.”

But East Los Angeles was still home for many. Rudy and his young bride brought their first house there and raised four children. Rudy’s sister, Ofelia, and her childhood sweetheart, Amado, also remained.

Amado had joined the Army in 1947 when he was 16 and blossomed into a fine athlete. He toured Hawaii for two years as a light-heavyweight boxing champion and missed a chance to try out for the Olympics because of a dislocated jaw.

He returned to the old neighborhood a star and took Ofelia to her high school prom.

Ofelia, who wanted to be a teacher, enrolled at East Los Angeles College. But, worried that she would be come a financial strain on her family, she quit and went to work at a downtown sewing factory. The job paid less than $1 an hour.

Amado and Ofelia married in 1951. As the first of nine children began arriving, Amado forgot about sports and his ambition to become a policeman. He supported his family on $50 a week earned as a rubbish collector. Later, he worked at a cloth mill and drove trucks. Sometimes he could not find work.

Ofelia and her sisters remember the 1950s as the decade they spent being mothers and wives. Most moved from East Los Angeles, but Ofelia stayed.

“Ofelia always wanted to stay in the community and help somehow,” Amado recalled.

At work, Amado was frequently asked by Anglo co-workers, “How can you live there?”

He grew tired of the offensive innuendo.

For Amado and Ofelia’s children, the little cracker-box house on the hill with a large backyard offered a sheltered environment. There were trees and giant maguey plants as well as a maze of prickly pear cactus that formed natural caves. In the children’s minds, the caves became castles and hidden passages where monsters and brave warriors fought to the death.

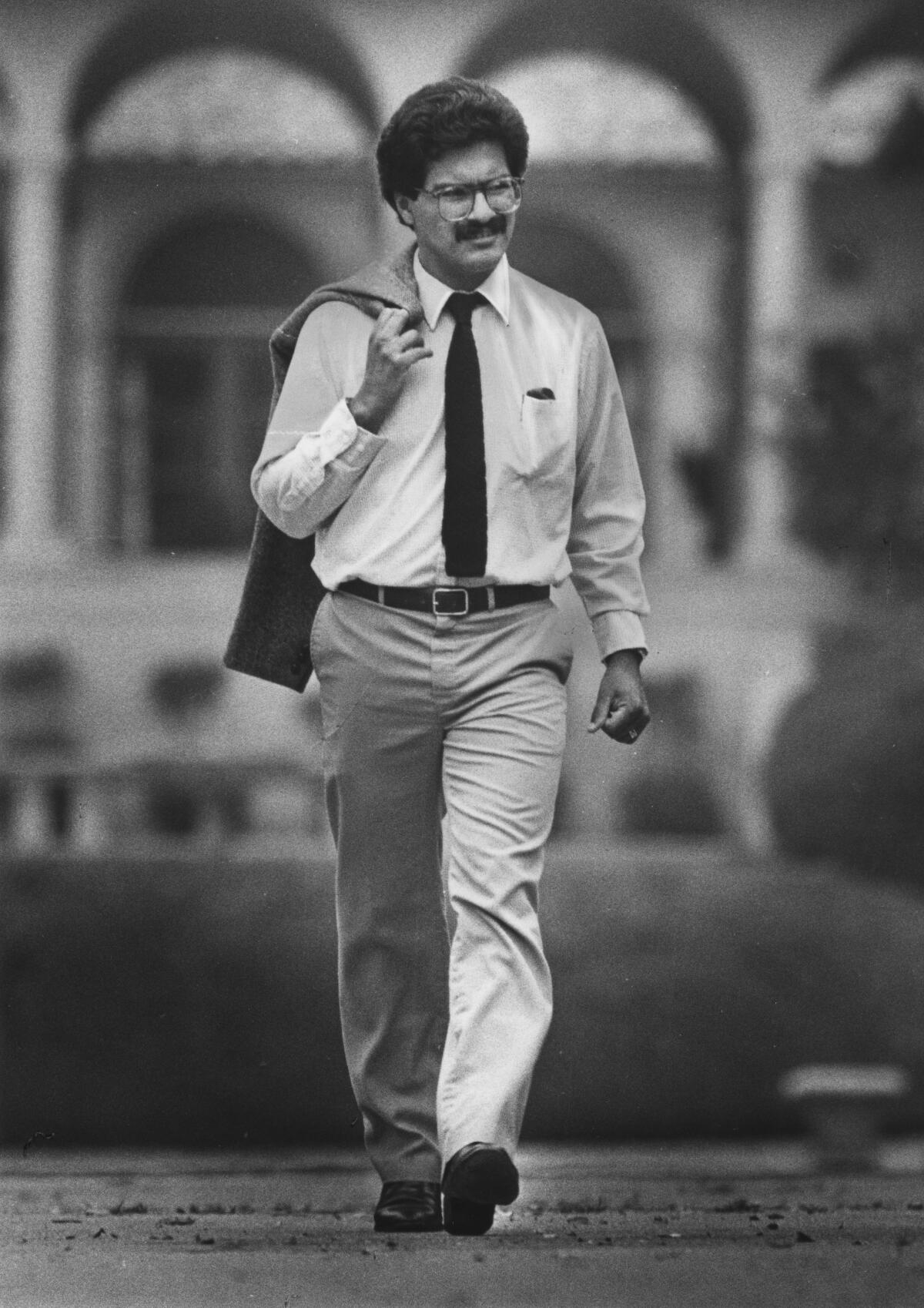

Years later, their son, Ben Esparza, credited his childhood experiences with developing his imagination and helping him in his work with physically handicapped children, as director of a special education clinic at California State University, Los Angeles.

There was another advantage, he said: “I never questioned my ethnic identity.”

For some youngsters, life in postwar East Los Angeles was troublesome. One of Rudy’s young brothers-in-law began hanging around neighborhood toughs from the El Hoyo gang and created such problems for his mother that she turned him over to Rudy to straighten out. Rudy was the one whom family members most often turned with disciplinary problems. Despite his intervention, some young nephews became involved with drugs and alcohol and dropped out of school.

Other youngsters venturing outside the barrio for the first time often found the experience unsettling. It happened to Rudy’s son, William, when the family moved to Whittier in 1970.

Whittier was a predominantly Anglo suburb at the time, and William remembers his brief time at a high school there as lonely and confusing. Uneasy around Anglos and “Anglicized” Chicanos, William opted to return to the same segregated but nurturing environment where his parents had grown up.

He moved back to East Los Angeles to live with his grandmother and attend Garfield High School.

“I couldn’t stand to be away. White people had always been foreign to me,” he said.

Years later, William marveled at the difference between him and a younger brother, who grew up in the suburbs.

“I can relate to his music and his surfing. . . . But in some ways he can’t get into me. He can’t imagine what it’s like cruising the boulevard, jumping fences or running through a cemetery at night with your friends.”

But if William has trouble relating to his brother in the Anglo suburbs, so doe a young cousin from Mexico have trouble relating to William and his family.

“They’re very Chicano . . . Americanized. We’re Mexicano,” said the cousin, Leticia Yniguez. “We don’t get excited about Fourth of July picnics. We’re not the hot dog-hamburger type of family. Our idea of a celebration is a wedding.”

This diversity within one family also illustrates how the cycle of immigration continues in East Los Angeles.

Leticia, 26, is the eldest daughter of Samuel Yniguez. Samuel is one of three sons raised by the family patriarch, Arcadio, after Arcadio’s return to Mexico four decades ago.

Samuel and his family moved to East Los Angeles in 1960 after a small grocery store business in Mexico failed. He has worked as a tailor ever since.

I was Samuel’s wife, Socorro, who encouraged her husband to make the move.

“I had one dream since we got married. That was buying our own home. I didn’t see much chance of realizing it in Mexico,” she said. Eighteen years after their arrival, they purchased a home.

“My brothers had come to work here. We had relatives and friends who had come. So I told my husband: ‘How is it that everybody risks going, even when they don’t have (immigration) papers. And you, who have them, aren’t willing?’”

The Yniguezes and other recent immigrants like them continuously renew the Mexican flavor of East Los Angeles, as they replace those who move to the suburbs. It is a process that perpetuates the barrio’s isolation.

::

While the Yniguezes were getting settled in East Los Angeles, a new political mood was developing among the more established members of the Mexican-American community. For the first time, they were becoming involved in large numbers in a presidential election.

Like many Mexican-Americans Guadalupe’s son, Rudy, was an ardent admirer of John F. Kennedy. Viva Kennedy clubs had sprung up in Mexican-American communities across the Southwest to work for his election in 1960.

Rudy also understood the anger and frustration of the black civil rights movement.

“I think the black, like the Chicano, has been abused for too long. Poverty has had a lot to do with it . . . no jobs, no food. I was sympathetic with their cause. Not the burning and looting. But it was time they made some noise,” he said.

Mexican farm workers also were making themselves heard. Led by Cesar Chavez, they began organizing in rural California, staging boycotts and strikes for better pay and decent work conditions.

Among the families working the fields of the San Joaquin Valley were the De La Rosas.

Some of the family’s ancestors came from Nochistlan, the same Mexican town that was home to Rudy’s father, the patriarch Arcadio. The parallel tracks of these two families—one rural, the other urban—crossed again in Los Angeles.

Rudy’s son, William, met Patricia De La Rosa while attending California State University, Los Angeles. Later, they married.

Patricia came from a family with deep roots in the farm workers movement. Especially her aunt Margaret.

Margaret married a bracero whom she met on the migrant trail when she was 18. He was one of thousands of temporary workers allowed into the country when the United States was at war and in need of farm laborers.

Margaret said her husband, Juan Govea, who had studied music at universities in Mexico, was a man with “liberated ideas.”

While working at railroad camps as a bracero, Juan spoke out on behalf of his fellow workers. During the late 1940s, after the couple settled in Bakersfield, Juan helped organize a chapter of the Community Service Organization. The group, based on the community-organizing ideas of Saul Alinsky, was viewed as a threat by the white community. Margaret recalled being labeled a “communist.”

And Juan Govea befriended the young Cesar Chavez, also a community service organizer. Chavez, who in time effected fundamental changes in California agriculture, made a strong impression on the family.

The Govea’s eldest daughter, Jessica, quit college in 1967 to devote herself full time to Chavez’s union effort. One of her first assignments was to travel to Canada to drum up support for the union’s grape boycott, called in an effort to pressure growers into signing union contracts.

“It was a total commitment of yourself,” she recalled. “And it was faith. The (union) effort was something so strong and so right that it had to happen. Changes had to be brought about.”

Jessica later served on the union’s board of directors. She left the organization about a year ago, and she took some lessons with her: “I learned about the obligation to share what I have with people and how to bring about social change.”

Chavez’s movement so inspired Mexican-Americans in the city that they began mobilizing. They, too, were angry at an economic system that had historically welcomed Mexican labor but refused to pay adequate compensation for it.

They demonstrated and marched for better schools and higher college enrollment. They joined the growing protests against the Vietnam War, in which Mexican-Americans were again dying in disproportionately high numbers.

A new generation of Mexican-Americans wrestled with the issue of ethnic identity and took it a step further, meshing it with a political identity as Chicanos.

Guadalupe’s children and grandchildren would be swept up by the times.

::

For Ofelia, who began working as a teacher’s aide and attending neighborhood meetings, the Chicano movement marked a turning point from housewife and mother to community activist. She also began developing as an artist. Her paintings were later shown at community exhibits.

“It’s like she’d been holding her breath for 15 years and then came up for air and took a deep, deep breath,” her son, Ben, said.

“I started listening to people who were raising their voices,” Ofelia said. “I saw a great need for change and I had to join them.”

As a teacher’s aide, Ofelia was irked by the lack of support from administrators and teachers for bilingual education programs. Remembering what it was like as a child to be forbidden to speak her mother tongue, she became determined to help a new generation of immigrant children avoid the same conflict.

She dusted off her old dream and went back to school to become a bilingual teacher, dividing her time between community activities, her home, her job and her studies.

As her world broadened, Ofelia found that the racist attitudes her generation had fought to dispel were still current.

“People developed the impression that if you speak Spanish, are dark and poor, you’re not very intelligent,” said Ofelia, who grew up fighting that definition herself. “I believe we have a right to achieve to our fullest and still keep our Mexicanness . . . .I have a right to speak my language and dress as I will. I have contributed to make this country what it is. My family and my ancestors have contributed.”

And there was Vietnam. Like a previous war, it left a mark on the family.

One of the first to go was the young son of Guadalupe and her third husband, Alberto Aviles. The boy, Albert Jr., was eager to match the example of his older brother, Rudy, whose wartime exploits were still admired.

At 18, Albert enlisted in the Marine Corps. He quickly became a corporal.

“I felt pride being Chicano and in knowing that across our family’s generations, we’ve been warriors. And I believed what they said, that I was going there to protect my country against communism,” he said.

But what Albert saw when he got to Vietnam filled him with doubt. “There was no sense of purpose,” he said. “I felt like the ugly American.”

In 1967, about a year after he left, Albert returned from Vietnam with a bullet wound through his head.

After he recovered, Albert went with his father to Mexico to fulfill a manda, a religious promise that his father had made in hope that his sone would come back from the war alive.

They went to the cathedral in San Juan de los Lagos, which attracts religious pilgrims from throughout Mexico. At the entrance of the large church, Albert’s father got on his knees and hobbled the entire distance to the altar. Albert watched from the side.

Looking back on that difficult period, Albert credited his family’s love and concern for getting him through.

Albert became an advocate for Vietnam War veterans and later noted that nearly 90% of the Mexican-American veterans he met had been combat soldiers. He came to see the war in Vietnam as “a systematic way of dealing with us . . . . If you were Mexican-American, you were going to end up in a combat unit, because you probably didn’t have an education . . . .It was like a systematic genocide.”

Albert said he still has nightmares and cries about “the things that happened” in Vietnam. Now, when he hears the latest news from Central America, he gets angry.

“I’ll be damned if I’ll let my nephews fight for nothing. I’ll march in the streets,” he said. “I stayed quiet last time. I’m not going to do it again.”

Others in the family were similarly affected by Vietnam.

Rudy, the veteran of World War II and Korea, tried to enlist for Vietnam when his younger brother, his eldest son, a brother-in-law and several cousins joined or were drafted.

But as the war dragged on, and other, younger members of the family joined the mass protests against it, Rudy’s views changed. He sided with his son, William, when William decided to avoid the draft.

Over the years, the family’s “warrior” tradition found a new expression. College diplomas and athletic awards began to replace the standard photo gallery of men in uniform on some family walls.

::

In the late summer of 1970, more than 20,000 people participated in an anti-war march in East Los Angeles. A riot later erupted after law enforcement officers moved in to disperse the crowd that had assembled at a local park.

Among the crowd were several family members, including Guadalupe, who had taken Rudy’s children to the park to listen to the music and speakers.

They arrived home safely, but three men died and hundreds of others were injured.

Among the dead was Ruben Salazar, a journalist who had earned the respect of the community through his columns about Chicanos in The Times. He was killed when a tear gas projectile, fired into a local bar by sheriff’s deputies, struck him in the head. An investigation concluded without criminal charges being filed.

But Rudy remains convinced that “the whole thing was planned.”

Rudy’s son, William, like many of his cousins, was in junior high school when the period opened. Many of these young Chicanos came to feel that the movement had passed them by. But it proved to be a political awakening, nonetheless.

William remembers it as a times when Mexican-Americans reassessed their belief in America’s promise:

“My parents began sizing up their duty to the country, their hard work and what the returns had been . . . .

“They remembered the zoot suit riots. . . . They saw police coming into our neighborhood . . . . Then there was the Salazar murder. They were trying to figure out what was going on.”

William’s cousin, Ben, became involved in a Marxist-Leninist Chicano group while attending Cal State Los Angeles.

“I had a lot of mixed emotions about what I was. Culturally, I was sure of my identity as a Chicano, Mexicano and as an American, because I was born here,” Ben said. “But I couldn’t identify with a society that spits on my own people.”

Ben left the group as internal turmoil began splitting it apart. Years later, he concluded that his identity was more deeply rooted in a strong sense of family than in any particular political ideology.

For Samuel Yniguez’s eldest, Leticia, the question of identity posed a different problem. She had strong ties to Mexico, and they were reinforced by family trips to Nochistlan. There, her grandfather, the patriarch Arcadio, “instilled pride in us,” she said. “He told us we could do anything and that nothing could stop us.”

Leticia recalled that “for a while, I wanted to be Chicana.” She found it difficult, however, to identify with second- and third-generation Chicanos, such as her cousins, who tried to show their cultural pride by wearing ponchos and huaraches.

Nor could Leticia accept the second-class status of Latinos in the United States as her own. Thus, she was unable to identify with a political movement fighting to improve it.

But she recalled being intrigued with the concept of Aztlan that was presented in college Chicano studies courses. Aztlan, the mythical homeland of the Aztecs, became a symbol of a Chicano Southwest.

It was appealing because Leticia, like many of her relatives, sees the Southwest and Mexico as one.

“There is no border,” said Leticia, who watches relatives come and go between the two countries at will. “It doesn’t really exist.”

By the mid-1970s, the marches and demonstrations had ceased.

Giving up the streets for what many called “a more sophisticated” approach, Chicanos began forming professional associations and became active in civil rights and grass-roots neighborhood organizations.

Many of the old leaders became lawyers, college professors and bureaucrats. They received government appointments and a few were even elected to office.

But for the majority of Mexican-Americans, things remained pretty much the same.

When Guadalupe looks back on her life and considers where Chicanos are today, she is somewhat pleased.

“We have a little more power and more representation. They can’t ignore us anymore,” she said.

But she is concerned that Mexican-Americans are losing touch with their culture. Her solution is family unity. “You have to have family unity,” she said.

Some of her grandchildren contend that the racism the family has battled for generations is still holding them and their community back.

Several are attending college and a few have entered professional fields, but most have not. For every teacher in the family, there are many high school dropouts and blue-collar workers.

Some are struggling in these recessionary times. Ofelia’s husband, Amado, has been out of work for nearly year. And he knows that he is not alone. Last year, the unemployment rate among Mexican-Americans in California was 15.3%, compared to 9.9% overall.

Amado, 52, spends his days puttering in his workshop, isolated by a wall of silence from his wife and their children. “I feel so damned useless,” he said.

Amado also feels betrayed after working 23 years for a trucking company that went out of business and left him without a job or pension. “You work all those years to get ahead and suddenly, you’re threatened with losing it all. . . .It shouldn’t be like that,” he said.

Ofelia, an ageless, dark-eyed beauty with high cheekbones of her Indian ancestors, has stayed close to her roots and become the keeper of the family’s history and cultural heritage. She is credited by a younger with helping them develop a sense of identity as Chicanos and as part of a community.

Ofelia worried that her participation in Chicano Movement activities could cost her a job. But in 1975, after becoming the family’s first college graduate when she was 43, Ofelia began teaching at City Terrace Elementary School, where she remains. Two of her sisters, one a teacher now, the other a foundry worker, also returned to college in their 40s, while working and still raising their youngest children.

Rudy, 57, remains a respected member of the family. His memories of unpleasant confrontations with racism are tempered with many good remembrances. He is not a bitter man. He remains optimistic and still buys into the American dream. He lives in West Covina and has a wide multiracial circle of friends. An avid sportsman, he looks forward to retiring and moving with his wife to the mountains.

Guadalupe’s family is as diverse culturally and politically as it is economically.

And although many point to this as a sign of progress, there is concern that it may be straining the family’s cohesiveness and that of the community it reflects.

Most of Guadalupe’s grandchildren no longer speak Spanish and some have abandoned their parents’ religion for more contemporary ones.

“Imagine, they don’t pray to La Virgen de Guadalupe anymore,” she said.

Some are growing up in mixed neighborhoods like Alhambra, where, to the amazement of those raised in the barrio, they are listening to new-wave music, dating Anglos and drifting away from the community and their culture. But some of their Mexicano cousins, like Leticia, remain close to the culture and others are returning to it.

Their elders complain that “the younger generation doesn’t know about what we went through.”

“I see a lot of kids in college who feel that they don’t owe anything to their community,” said Jessica, the former Cesar Chavez campaigner, who has returned to college at 36. “We have a lot more of everything than before—more legislators, educators, more kids in college—but something’s missing.”

Recalling the intensity of the 1960s and the concessions that were won, Ofelia is frustrated by cuts in school funds at a time when Latino students are quickly becoming a majority in city schools.

“I see us backsliding . . . .After the movement, people thought, ‘Now everything’s going to be all right,’ and they didn’t continue working at it. Instead, people became specialized, concentrating on their own field,” she said reflecting on her own experience.

Others complain that upward mobile Chicanos have become complacent with their middle-class trappings.

Rudy’s son William, now assistant dean of students at Occidental College, said the present generation is living “a life of contrasts . . . .They seem divided. Many of them are being opportunistic and losing a lot of cultural things. They haven’t taken the time to look at their own history and develop the appreciation for what we have . . . .Some of them do.

“I don’t know what is winning out.”

Still, there is faith in La Raza’s endurance.

The family’s leading members continue to focus attention on family history and heritage and are determined to pass it on to their children. Reflecting a trend in the community, several have taken to calling themselves Mexicanos, coming full circle with the term that Guadalupe has always used. It is a way of connecting with the past as well with continuing immigration from Mexico.

Ofelia’s son, Ben, expressed it this way:

“The family stories—like the tales we were told in school about George Washington—have given me a strong sense of where I’ve been, so that I can better understand where I’m going.

“I know about my grandmother’s struggle as a Mexican woman in a new country . . .and about my parents’ struggles. And when you put all the pieces together you come up with one thing: the importance of family, of belonging to a group.

“I’m the evolvement of a piece of history . . . .I think that people who have lived on the same land for generations have a feeling for that land. My ancestors have died and been buried here and they are part of this land. Los Angeles is our home.”

::

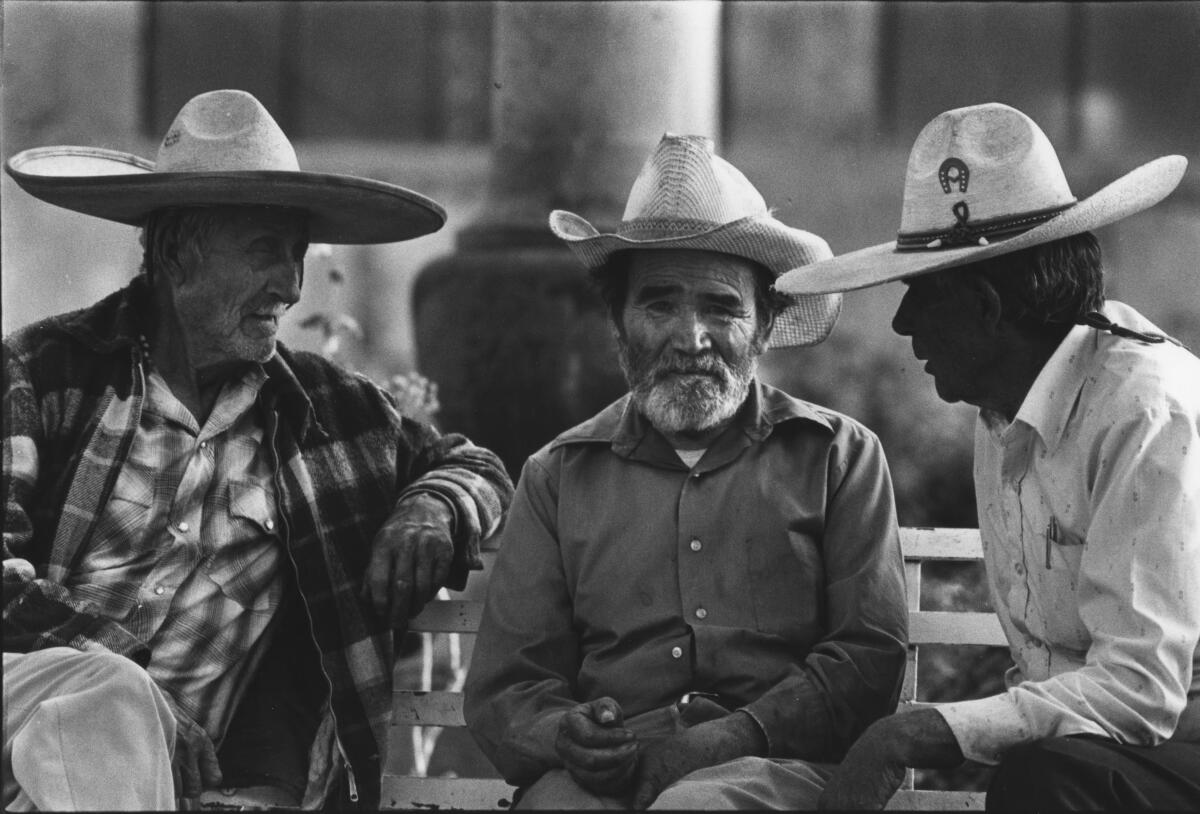

In the Mexican town of Nochistlan, where the family’s story began, much remains the same as at the turn of the century, when young Arcadio Yniguez walked its cobblestone streets.

Women wrapped in their rebozos and horsemen in wide-brimmed charro hats still populate this dusty town where stories of hidden treasure are still told and folk healers practice the medical arts if their Indian ancestors.

And young men still wonder, as Arcadio did before he began his turn-of-the-century journey north to Chicago, whether a better life awaits them beyond the surrounding hillsides. The average daily wage in the drought-ridden region is about $2.

Pioneers like Arcadio and the thousands who have spun an intricate web of family ties that bridge two realities and perpetuate the timeless process connecting two countries.

Now, an occasional Los Angeles-style cholo, in khaki pants, white shirt and derby hat, strolls under the Spanish colonial-style arches of the marketplace. Pickup trucks with California license plates share the streets with cattle.

On a recent evening, 22-year-old Alvaro Jimenez, a distant relative of Arcadio Yniguez, paused athe town’s central plaza, an oasis in the middle of white-washed adobe homes and a cactus-studded-countryside, to ponder the future.

Like most of his relatives and friends who come and go between the two countries, Alvaro is part of the latest generation of immigrants from Nochistlan. “It is very rare to find a man in town who hasn’t gone to El Norte,” he said.

Recently Alvaro returned home after a year of working in California. Along the way, he visited his uncle, Samuel Yniguez, the tailor, in Los Angeles.

“This time I almost didn’t come back,” Alvaro said.

But he is still not sure whether he will settle in Mexico or in the United States.

“I have family in both places. To me, it’s pretty much the same here or there,” he said.

Those who remember the patriarch Arcadio’s restless spirit and self-composed manner find a likeness in young Alvaro Jimenez.

Asked what he remembers of his forerunner, Alvaro shrugged.

“I’ve heard the name, but I don’t know much about him. He died some time ago, didn’t he?”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.